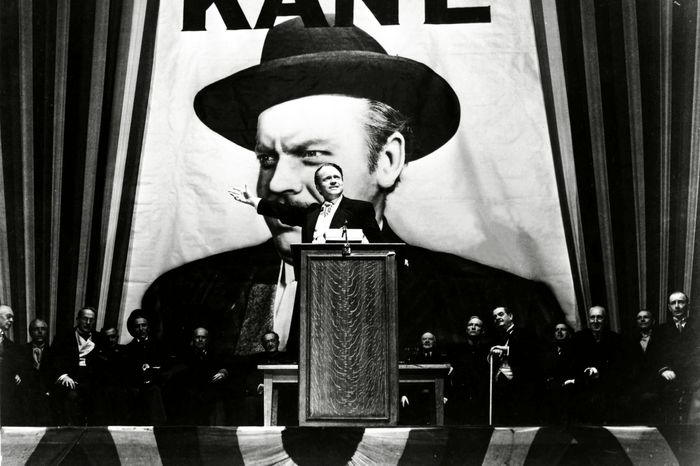

If there’s a film likely to be in Oscars contention — because God knows the Academy loves a film about filmmaking — David Fincher’s Mank, a black-and-white time capsule shot in loving but unromantic reference to the past, is the one. It’s the story of Herman J. Mankiewicz, the booze-soaked but brilliant writer of Citizen Kane, whose collaboration with Orson Welles would make for the most febrile and gorgeous piece of American filmmaking, maybe ever. Dense with allusions, references, and casual name-dropping, Mank is both steeped in Hollywood lore and bold in its lack of explanation of said lore. Fincher employs a merciless storytelling strategy that’s well-suited to the movie’s curmudgeonly main character; as Mank wrote of Hollywood to a friend in 1926, “Millions are to be grabbed out here, and your only competition is idiots. Don’t let this get around.”

In an attempt to elucidate some of the historical and cultural context needed to understand Mank, I’ve compiled a brief rundown of everything you need to know about Old Hollywood before you hit play on Netflix. The Classic ABCs of Mank, if you will, in a simple glossary format. Don’t let it get around. Or do. Unsuspecting Netflix perusers will need it.

Anti-Communism in Hollywood

Although the notorious McCarthyist witch-hunt era began in earnest after WWII, the stirrings began in Hollywood much earlier. During the Roosevelt years, many progressives would join the Communist Party, which positioned itself at the forefront of anti-fascism in an era that saw the rise of Mussolini and Hitler. Simultaneously, conservatives like John Wayne and Walt Disney would form the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, a group of film-industry figures willing to out their colleagues as communists to Congress. William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper mogul and inspiration for Charles Foster Kane, found himself on one side of this political divide (the right), while artists like Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles very much found themselves on the other (the left). It’s no surprise they were eventually headed for collision.

Back Lot

Much of the action we see in Mank takes place on soundstages and back lots, which most audiences take for granted, a simple part of the grand old movie-studio system in the days before CGI. But studio back lots, like the ones at Paramount or MGM, were much more than just a collection of sets: They were the beating heart of the Old Hollywood system. They sustained thousands of employees from electricians to hairdressers to movie stars, featuring their own doctor’s offices and police stations, stretching tens of dozens of acres across the spacious California backwoods. The MGM canteen fed 2,700 people per day; extras dressed as circus actors and ancient Romans surreally wandered the lot. Fincher gives us a chance to go back in time to marvel at these fantasy factories — which are today mostly dismantled — in their heyday.

Cosmopolitan Pictures

Cosmopolitan Pictures was a New York–based film company founded in 1918 by newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst, who later moved the company to Hollywood. Such were the vast reserves of Hearst’s wealth that he could afford to build an entire studio largely perceived to be devoted to projects for his mistress, Marion Davies. Never mind that Davies was a talented comedienne in films like King Vidor’s Show People (1928), Hearst insisted she play loftier (and ultimately more ill-suited) roles for their flagship company.

Deep Focus

You’ve heard film types and cinephiles talk about “depth of field” before, but if you didn’t know: Deep focus is when every plane of a shot — the foreground, middle ground, and background — is in focus at once, giving a certain depth and complexity to the image. It wasn’t invented by cinematographer Gregg Toland on the set of Citizen Kane, but Toland’s use of it is considered a pinnacle of the technique, employing lenses and lights that made it easier to achieve the effect in the early 1940s.

Economic Crisis

In one memorable scene from Mank, studio head Louis B. Mayer tells his MGM staff that they have to take a pay cut because of, well, the Great Depression. In point of fact, this actually happened. It may seem in retrospect that Hollywood was the one place that was Depression-proof, but at one point MGM had to either cut wages by 50 percent or shut down the studio altogether.

Fitzgerald

A blink-and-you’ll-miss it reference to F. Scott comes when Herman J. Mankiewicz is on the phone and makes a joke about how it’s awfully bad news if Fitzgerald — a notorious alcoholic — is calling him a “ruined man.” The literary giant was essentially washed-up during this period; in spite of his enormous fame in the 1920s, by the ’40s he was broke and had failed to find any real success in the screenwriting business. The travails of working with the great author in this sad period is loosely fictionalized in the novel The Disenchanted, written by another major Hollywood figure: Budd Schulberg.

Grapes of Wrath

The year before Citizen Kane, cinematographer Gregg Toland shot another masterpiece in black-and-white, this time with director John Ford. The Grapes of Wrath is an adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel about a desperate Oklahoma family that’s been displaced by the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression. The concerted effort at the time to keep California in Republican hands — a campaign that features in Mank — was focused on the maligned “Okies,” presented as a horde of hobos invading the state. To get an idea of who and what people like Louis B. Mayer and William Randolph Hearst were trying to vilify as part of this effort, watch Grapes of Wrath.

Hedda and Louella

Mank contains a brief mention of these two notorious women — and by their first names only, which suggests their level of power. Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons were the two biggest syndicated gossip columnists in Hollywood and were known to be vindictive if crossed. If Hedda or Louella took a disliking to an up-and-coming star, they could kill careers in the cradle. They had informers all over Los Angeles. Hedda was famous for her staunch conservatism, and both were deeply in thrall to the Hearst newspapers. Like good watchdogs, both would also launch scathing attacks on Citizen Kane, helping to diminish Welles’s reputation in Hollywood.

Irving Thalberg

Maybe the most relentlessly mythologized movie mogul in history, the “boy wonder” Irving Thalberg practically invented the role of creative producer. He’s seen in Mank as the right-hand man to Louis B. Mayer, though much different in temperament to his boss. Thalberg was the first to introduce test screenings for select audiences. Sensitive, bright, and creative — though never beyond ruthlessness — his premature death at age 37 would leave an enormous void in the MGM hierarchy.

Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Writing for the screen was not a talent solely reserved for the older Mankiewicz sibling. Young Joe, Mank’s kid brother in the movie, is just getting started in the 1930s, but he would go on to become a garlanded writer-director with films like A Letter to Three Wives, All About Eve, and Guys and Dolls. He would also wage a courageous fight against the forces of McCarthyism as head of the Director’s Guild in the 1950s.

Kane’s Inspiration

Born to a gold-rush tycoon of the old West, William Randolph Hearst began his vast newspaper empire in the late 19th century and would greedily gobble up a host of other publications until he had amassed monolithic power. He ran for political office several times to no avail and was referred to as “the most hated man in America.” When Hearst learned about Citizen Kane, he did as much as he could to obstruct its release.

Labour Struggles

The politically fraught 1930s saw Hollywood workers organize and unionize en masse, forming guilds like the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and the Writers Guild of America (WGA). In a tale as old as time, the powerful, well-paid moguls — especially Hearst and Louis B. Mayer — did what they could to discourage their employees, often conflating “pro-union” with “communist.” Mayer even formed AMPAS — yep, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, as in, the Oscars — in an attempt to offer a distracting replacement for a real union. It’s against this contentious backdrop that much of Mank takes place.

Marion Davies

Davies was the longtime live-in mistress of Hearst and a Brooklyn-born flapper comedienne (played by Amanda Seyfried in the film). She was cruelly skewered in Citizen Kane, owing — at least in Fincher’s version of events — to the resentful and unrequited feelings Mankiewicz had for her in real life. Davies was in fact a peppy, refreshing screen presence with a gift for imitations of other stars and good-natured physical comedy. Welles, for his part, later recanted his portrayal of Davies in his film, pointing out that she was far from the untalented Susan Alexander Kane in real life.

Nazi Ban

Fun fact: In the 1930s, Nazi Minister of Culture Joseph Goebbels banned all work written by Mankiewicz unless his name was removed from the screen credit.

Orson Welles

The legendary maverick of American cinema began his Hollywood career with the high point of Citizen Kane, after garnering nationwide fame from his 1938 radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds. Welles was recruited by RKO Pictures and brought to Hollywood, age 24, initially to adapt Joseph Conrad’s classic novel Heart of Darkness. When that fell through, Welles apparently had a meeting with Mankiewicz that concluded with them agreeing to work on a picture together.

Pauline Kael

Highly influential film critic Pauline Kael wrote a controversial — and somewhat discredited — essay in 1971 entitled “Raising Kane.” Within, she argued that Herman J. Mankiewicz was far more of a force in the creation of the “world’s greatest movie” than Orson Welles, who she alleged had downplayed the screenwriter’s contributions; Welles accepted the Oscar for Best Screenplay on his own. Although her ethics in reporting the piece have since been called into question, it’s said that early drafts of the Mank screenplay, written by Fincher’s late father Jack, were guided by Kael’s essay. The version that made it to the screen, however, is far more charitable to Welles.

RKO Pictures

RKO, or Radio-Keith-Orpheum, was founded in 1928 and was the studio responsible for Citizen Kane. Around the time of the Depression, its output included the classic King Kong (1933). Historically, it was smaller and much less profitable than the other Big Five studios, but it was home to a clutch of unforgettable talent, from Kane cameraman Gregg Toland to Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

Screenwriters

In a flashback to the early 1930s, during Mank’s days as a screenwriter for Paramount, Fincher shows us around the writer’s room — a chummy, smoky boys’ club where figures like Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht were yet to fulfill what was arguably their greatest screen achievement: His Girl Friday (1941). The group spent much of their spare time gambling and bullshitting; they produced confoundingly brilliant work, but often faced the lowest of stakes. Writers were low down on the studio totem pole in the Golden Age. Most screenplays during this era could be swapped around, censored, and changed to suit producers’ whims. It was typical to put a number of writers on a project and credit only some of them, and they tended to swing from studio to studio in search of better gigs and creative fulfillment.

The Last Tycoon

F. Scott Fitzgerald may not have had much luck as a screenwriter, but his last great unfinished novel, The Last Tycoon, was largely based on Irving Thalberg’s short life. The story follows the main character’s rise in Hollywood and his struggles against a character based on MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer.

Upton Sinclair

The novelist and social reformer ran for California governor in 1934 against Republican candidate Frank Merriam, prompting widespread fearmongering efforts to paint him as a hardline communist by the conservative media and William Randolph Hearst. Hollywood studio heads, from Louis B. Mayer at MGM to Walt Disney, encouraged their employees not only to hate Sinclair but to take part in phony anti-Sinclair newsreels, and even garnished some of their employees’ wages for the opposition candidate. In Mank, the media smear campaign against Sinclair by Hearst is shown to be one of the primary drivers behind Mankiewicz’s hatred for the mogul — and his eventual penning of the Citizen Kane screenplay.

William Faulkner

Mankiewicz was far from the only writer who looked down on the machinations of Hollywood; the legendary Faulkner was very much in agreement with him. The man who adapted works like The Big Sleep for the screen probably said it best: He saw Hollywood as “the plastic asshole of the world.”

Xanadu

“Besides the Pyramids,” goes the newsreel voice-over in Citizen Kane, “Xanadu is the costliest monument a man has built to himself.” The lavish palace is home to Charles Foster Kane, replete with an entire zoo, a Venetian canal and gondoliers, and a museum’s worth of priceless antiquities. Of course, Xanadu is a fictionalized version of San Simeon, known more widely as Hearst Castle. It’s there that we see Mankiewicz go for various drunken soirées — and a wee-hours wander past the giraffes. The best part? If you want to see the real thing, you can still visit the original Hearst Castle, located a few hours south of Monterey, California.

Yellow Journalism

Yellow journalism, race-baiting, and scandal-mongering were the name of William Randolph Hearst’s dirty game; he was something like a progenitor to Rupert Murdoch. This is the kind of media landscape Citizen Kane was taking aim at at the time.

Zanuck

Darryl Zanuck — played by Trevor Wooldridge in Mank, in one of the film’s many uncredited roles depicting a major Hollywood player — was a producer and executive who played a major part in forming the Hollywood studio system (namely, 20th Century Fox), and who went on to have one the longest Hollywood careers, eclipsed only by another end-of-the-alphabet colleague, Adolph Zukor, founder of Paramount. Other figures who pop up in Mank, some played by credited actors and others not: Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Geraldine Fitzgerald, George Schaefer, Carole Lombard, Bette Davis, Charlie Chaplin, George S. Kaufman, Josef von Sternberg, Norma Shearer, Eleanor Boardman, Billie Dove, Clark Gable, Eddie Cantor, and S.J. Perelman.