There is only one way for any musical to possibly begin: the sounds of an orchestra tuning to A, backed by the crinkles of the crowd unwrapping their Werther’s. From this place of reliable uniformity, there are any number of possible directions a musical can go, from commercial to experimental, from horny cowboys, to horny newsboys, to horny convicts in a Jazz Age women’s prison. And because Broadway is as a diverse art form as any — because there is an endless (pun acknowledged) variety of “I Want” songs and 11 o’ clock numbers and love ballads — composers and playwrights assumed they could just go ahead and end a musical any old kooky way too. But that is incorrect.

Not to sound too much like some sort of scoldy Henry Higgins, but what I’ve come to realize is that there are only two acceptable ways for any musical to end. Comic or tragic, mainstream or weird, old or new, there are a ton of musicals that fall into the format of the Only Two Good Possible Ending Types. They cover the spectrum of human emotion and energy. Sometimes they encompass a reprise or encore, although they don’t have to. You might find that your favorite musical’s ending does not qualify as acceptable. The Sound of Music, for example, does not fit into either category. Its ending is therefore bad, even though it features the objectively Good Thing of its protagonists escaping literal Nazis. Les Misérables, as well, does not meet the Good Ending criteria; apologies to that ghost chorus.

Since Broadway isn’t opening any time soon, I expect producers to take notes on this and adjust their shows accordingly, so that they can end in the only ways that matter:

We’ve Come Full Circle Back to the Beginning But Now It’s Really Poignant

As Hilary Duff once said, “Let’s go back, back to the beginning, back to when the earth, the sun, the stars all aligned.” Many musicals end with the story looping back to its opening, presented to us once again with two hours of context and wisdom giving the same scenario a new and more complex shading. These endings impress in the same way that timefuck movies (your Mementos and what not) do, only with way more emotional intelligence. They resonate for their meta rumination on the power of oral tradition, and how we learn and grow and build a culture out of retelling stories. It’s Brechtian, too, taking us out of the simple linear narrative and reminding us of the confines and construct of the eight-shows-a-week stage-play format, in order to teach us and stick with us. These endings are usually poignant, sometimes bittersweet or devastating, often haunting. The characters have been through something, and so have you, the audience, and we are all doomed to learn these same elemental, musical lessons again and again, because we’re humans. When pulled off, they send a chill down your spine. A ton of musicals employ this ending, and it basically works every time always.

Wicked, for all its blockbuster flash, is grounded by this framing device. The citizens of Oz sing “No One Mourns the Wicked” before Glinda the Good Witch flashes back to a Wizard of Oz prequel, so that by the time we reach the end of the musical, directly following Elphaba’s disappearance, we know a lot more about how she, Glinda, and basically every Wizard of Oz character got to this moment.

Into the Woods is another fantastic example of this. Sondheim’s musical is explicitly about the oral folklore tradition as a way of coping with and explaining tragic and futile circumstances, and it’s about the cost of knowledge. The fairytale ends exactly the way it started: After all the happily ever after, Cinderella is still left foolishly wanting, singing a dissonant, hanging, “I wish …”

Hadestown swaps European fairytales for Greek myth with its own spin on this ending: Andre de Shields’s messenger Hermes sets up the story of the doomed lovers all over again, and the chairs and tables are brought back to where they were at the onset. “It’s a sad song, we keep singing even so […] And we’re gonna sing it again and again,” because we need to believe that it will work out better the next time, and we need to go to theaters for the communal catharsis of when it doesn’t.

Once on This Island does the same with French Antilles oral tradition, ending with “Why We Tell the Story,” which acknowledges the heartbreak of Ti Moune’s story before insisting that it be told again to future generations, because they can learn from it.

Merrily We Roll Along is a musical told backward, so rather than looping back to the beginning, it begins at the end and ends at the start. To see the character’s youthful hopefulness in light of what we know is going to befall them just devastates. Of all the timefuckery inherent to this One of Two Types of perfect musical ending, Merrily is the most timefuck-y of all.

Fuck It, Let’s Have a Dance Party!

If you’re not going to end your musical with a bittersweet reflection on the simultaneous necessity of oral tradition and futility of human folly, you may as well dance! Dance-party endings can be interactive and participatory, sometimes encouraging audience members to come onstage or else just get up and boogie in the aisles. This is not the only way in which dance-party endings bus it past the proscenium; they can overlap with the curtain call, blurring the line between character and performer. At their best, dance-party endings conclude with the performers’ heavy breathing through smiles as they hold their final poses, sweat on their brows from leaving it all on the stage. They are so in their bodies, and so of their bodies, that it is infectious; you are compelled to dance, or at least to strut back to your car/Uber/subway, newly invigorated. The dance-party finale more often than not appears in shows with pop-centric scores; it is a contemporary invention, throwing decorum out the window in its exchange of energy. These endings can be seen as lowbrow or base, but they’re euphoric. They’re pure, gleeful, dorky abandon.

Hair is an early example of the dance-party finale, ending with Claude encouraging audience members to get onstage and writhe with the hippies. Along with the nudity and the flag nonsense, this was yet another transgression on Hair’s part; it’s the “fuck it, let’s dance” ending that pushed Broadway forward.

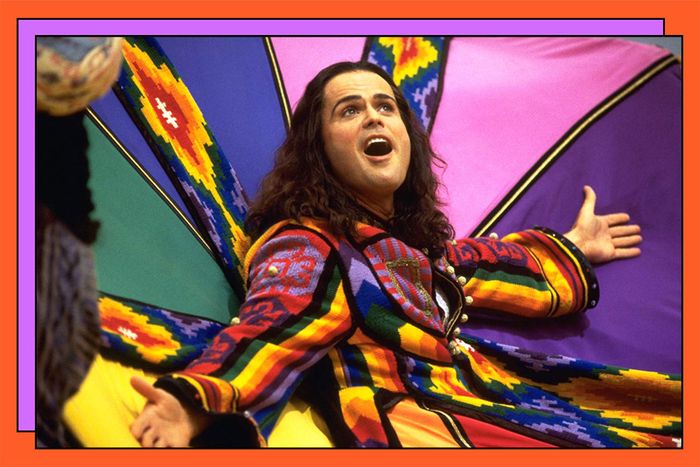

Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat ends with that most divine of Broadway finale formats, the megamix. The act of running through the greatest hits of the show you just staged is such a flex. It immediately memorializes Joseph as one of the great pop Broadway scores. It’s a party celebrating itself. It’s the best thing Andrew Lloyd Webber has ever done. And it’s adorable to see the children’s choir (a staple of most Joseph productions) up there having fun.

“You Can’t Stop the Beat,” the finale to Marc Shaiman’s Hairspray, is possibly the ur-example of the dance-party ending. Here is an ending number that keeps going for what feels like a thousand tireless verses, cementing the catchiest chorus in audience members’ heads until the end of time. The energy is high. The jazz hands are splayed. That last note is long. On last week’s “Rusical” episode of RuPaul’s Drag Race, famous theater kid Anne Hathaway said she loves drag because it’s a “transgressive act of joy.” Same goes for the dance-party ending of Hairspray.

Mamma Mia! is this section’s requisite jukebox-musical entry, because it’s the subgenre where dance-party endings truly thrive. In keeping with the “boozy moms’ night out” of the whole musical leading up to its finale, Mamma Mia! ends with a dance party set to an Abba medley ending in “Waterloo,” a song everyone knows and is encouraged to clap and boogie along to. If Mamma Mia! is the 21st century’s purest answer to the Shakespearean comedy of Elizabethan England (and believe me, it is), then the “Waterloo” dance-along ending is the part where the peasants in the Globe Theatre floor seats get to cackle and stomp and throw their rotting teeth at the stage or whatever.

The dance-party ending has become extremely popular over the past 20 years in movies aimed at kids, possibly stemming from the pop-heavy end of Shrek. Outside of animation, the best example of this is the “We’re All in This Together” basketball court dance number finale of High School Musical. It’s a piece of choreography so iconic, so tailor-made for kids at home to learn the moves and join in, that the Disney Channel aired separate dance-along screenings featuring tutorials. The power of High School Musical and its breakout-hit finale dance party number basically single-handedly fueled a cultural trend that would lead to the global domination of Glee. But that’s an essay for another list.

Bonus Third Category That Still Isn’t Acceptable But Honestly Is Too Charming a Trope Not to Mention So It Very Nearly Gets a Pass: Vehicle Hurtles Into the Sun

My system is perfect, I have effectively codified the full spectrum of effective musical endings, and this is not open for debate. But there is one more smaller genus of musical ending that I’d be remiss to ignore. It’s the kind where a vehicle whisks our main characters away directly into the sun. It happens with Danny and Sandy in a flying car in Grease, and it happens with Grizabella in some sort of hot-air balloon chandelier at the end of the movie version of Cats. These endings are transcendent and they are too nonsensical for me to ascribe any meaning to them. They beg to be perceived, but not understood.

More From This Series

- Harrison Ford Didn’t Do It

- What Makes Viewers ‘Tune In Next Week"?

- How I Learned to Love Dying (in Hades)