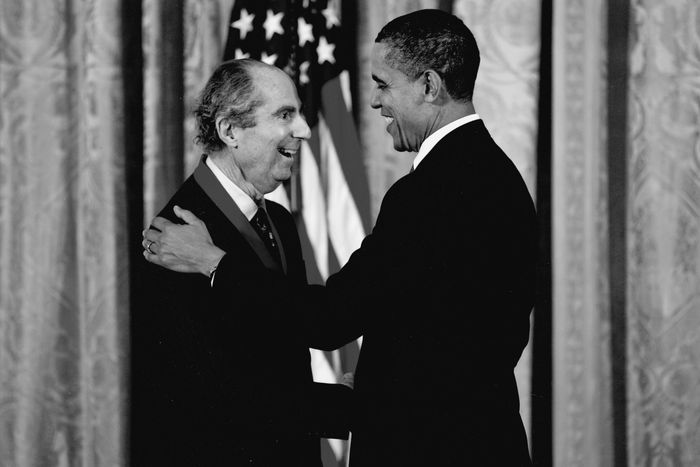

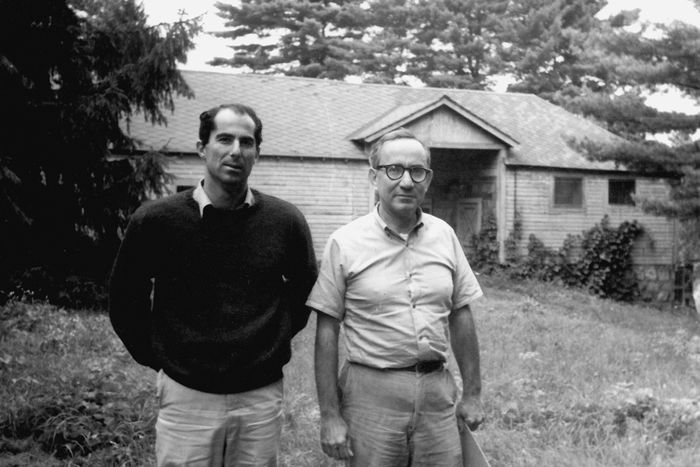

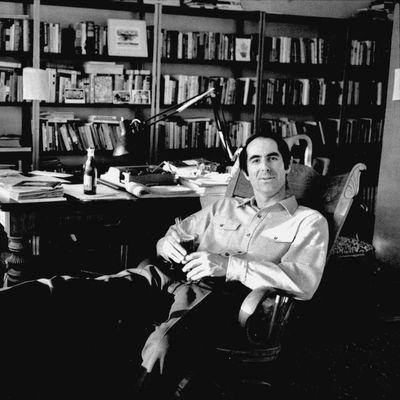

Indisputably a great American novelist, Philip Roth has a decent claim to be the great American novelist: a philosopher and a satyr, cranky and profound, one of the foremost interpreters of what he called “the indigenous American berserk.” The winner of just about every prize literature has to bestow, he was denied the Nobel, quite possibly because he was, over his 31 books, an inveterate controversialist. There are those for whom he will always be the author (and alter ego?) of Alexander Portnoy, the protagonist of 1969’s Portnoy’s Complaint, whose most famous transgression stands alone in American literature: the act of making love to a piece of liver, his family’s evening meal. Roth wrote in a register all his own, the voluble yawp of the aching analysand — “the aria bit,” his friend and sometime antagonist Alfred Kazin called it. When he died in 2018, after publicly retiring six years before, he left behind a rich, complicated legacy. He’d spent decades writing unsparingly about himself and versions of himself, avatars in the funhouse mirror: He was and he wasn’t his characters Nathan Zuckerman, David Kepesh, and Portnoy, all of whom got versions of his own life experiences; by the time he published the trippy Operation Shylock (1993), the plot hinged on a novelist named Philip Roth’s search for an impostor Roth. But he was equally unsparing to those he knew, loved, and fictionalized. He was generous to struggling writers and young women who interested him but also had a long memory for grudges and a host of uncurrent opinions. (“You used to be able to sleep with the girls in the old days,” he told Saul Bellow. “And now of course it’s impossible. You go to feminist prison; you serve 20 years to life.”)

This is fertile ground for a biographer. It is also dangerous territory, with a living subject with his own opinions to share and his own scores to settle. By the time Bailey agreed to write the book, with the promise of full autonomy, Roth had run through — or run off — a few previous picks for the job, most notably a former friend, Ross Miller, with whom he’d had a bad and fairly public falling out over its direction. But Bailey, who has written biographies of writers John Cheever, Richard Yates, and Charles Jackson, persevered and was given unfettered access to Roth’s papers, contacts, and candor. “I don’t want you to rehabilitate me,” Roth told him. “Just make me interesting.”

The resulting book, Philip Roth: The Biography, has landed, even before its April 6 release, with the force and splash of a cannonball. (It weighs in at 898 pages.) Roth was nearly as divisive as he was renowned, and his biography has been discussed and debated more widely than the usual door-stopper bio: David Remnick wrote about it in The New Yorker, Bailey was profiled in The New York Times Magazine, and early reviews have both praised his comprehensiveness and questioned his perhaps overweening empathy. “This one is more stressful than my Cheever book,” Bailey admitted when we spoke this week. “It’s very hard to please everybody with a biography of Philip Roth.”

Update, Tuesday, April 27: After allegations of sexual assault against Bailey by a number of women were made public last week, W.W. Norton & Company first paused distribution of Philip Roth: The Biography, then today announced it would permanently put out of print both the Roth biography and Bailey’s own earlier memoir. “Mr. Bailey will be free to seek publication elsewhere if he chooses,” a Norton spokesperson said in a statement. “In addition, Norton will make a donation in the amount of the book advance for Philip Roth: The Biography to organizations that fight against sexual assault or harassment and work to protect survivors.”

Maybe we can start at the beginning. Roth was a live subject in every sense of the word. I have to imagine there was a book Roth wanted to have written and a book you wanted to write.

I’ve gotten very good over the years about going my own way. Philip certainly tried to influence me. I have the hundreds, possibly thousands, of pages that he wrote directly to me, trying to influence my judgment on certain themes and episodes in his life. I took those obviously into account. But I also took into account the other 200 people that were interviewed, and all the documentation, and so on. I very much declare ownership of this book. I think it is a very independent-minded production. Would Philip be happy with it? I think he essentially would. But I think that there were certain things in it that would have been extremely mortifying to Philip.

I’m asking because it’s something that’s come up in some of the reviews. I’m sure you saw the Times review…

That was brutal.

“Complicitous” is not a word I think any biographer wants to hear.

There are certainly some nuance-minded people in between, but people tend to love Philip or hate him. If you love Philip, I’m way too hard on him. And if you hate him, I can’t possibly be hard enough. But you need to reconcile what Parul said and what Laura Marsh said with what David Remnick says, which is that I am uncowed, that I have “let the repellent in”; with what Claire Lowdon said in the Times of London, that it’s fairly brutal. A lot of people said that approvingly. You have to have a pretty skewed agenda to read my book and think that I’m letting Philip off the hook. Do I give air to his better qualities? I certainly do, and they were numerous. He was in many ways a darling man.

You quote Mildred Martin telling Roth in his earliest days, “If you’re going to be a satirist, you’re going to be misunderstood all your life.” He certainly seems to have felt that.

He did. He wanted the public to perceive him as sort of somewhat above it all. But really one of Philip’s most endearing qualities was that he was extremely vulnerable. He was flayed. I mean, Claire Bloom’s book devastated him. He never responded publicly, but he never got over it.

One thing that comes through very strongly is his sort of his zealous desire to make himself understood on his own terms. That must be a minefield for a biographer, since those aren’t necessarily your terms. Can you talk about how that dynamic played out between you?

On an everyday level, relating to each other, we were very chummy. We had a very nice rapport. I did not openly discuss, unless he confronted me, what sort of conclusions I was reaching. I let him do the talking. I think it was our last formal interview — I went to his apartment on the Upper West Side, and he was recovering from an aortic valve replacement. He was feeling really shitty. I mean, he had been housebound for weeks, barely able to go to the bathroom, that’s how enervated he was. I had come from Andrew Wylie’s office, and I had seen something that had provoked my curiosity, that was offensive to him. So I kept questioning him about it. And he kept saying, “I’m not going to answer that. That’s not in my interest to answer.” And he started getting worked up. And he kind of shifted around in his Eames chair and said, “This is the best I’ve felt in weeks, fucker!” That was very Philip. He could do the whole sort of baleful, browbeating stuff. But you could always, or almost always, appeal to the humor that was just a hair’s breadth under the surface.

I was quite capable of pushing back on Philip, too, when he was hassling me. I told him, first of all, about Ross Miller, my predecessor — I said, “You guys were best friends. I’m fond of you, Philip, but I’m not your best friend.” And I would try to remind him of that. For the most part, Philip really did try to kind of respect that difference. He knew we had a binding agreement. He knew he had to cooperate and make himself accessible to me. And he knew I was going to let the chips fall where they may.

Can you give me an example?

The main bone of contention between Philip and me was the model for Drenka. I call her Inga Larsen in my book. And Philip and I went back and forth about this. First, he thought that she didn’t deserve the protection of a pseudonym. I said, that’s a violation of our agreement. If she will only talk to me pseudonymously, then then that’s something I’m willing to grant. Finally, I thought that we had resolved everything, and very near the end, I think in early 2018, because Philip knew he was getting close to the end, he asked if he could see my interview transcripts with Inga. It was understood between us that I did not have to show him anything of that sort. But I was so worn out by then on the subject of Inga specifically, and my heart went out to Philip, because he was dying. And this was eating him alive. He was terrified of what had been disclosed. So I showed him the transcripts. I wonder whether they hastened his end. He found them very harrowing. I very much tell Inga’s side of things in my book.

Tell me a little bit about the process of reporting the book. Many people spoke to you, but certain key people — for example, Maxine Groffsky, the inspiration for Brenda Patimkin in Roth’s first book, Goodbye, Columbus — declined to. As a biographer, how do you understand people’s willingness or reluctance to participate?

I think one of my strengths is that I’m good at getting someone’s trust. For example, Maggie’s daughter, who I called Helen in the book … I helped her recognize that Philip was an important subject and that her story about Philip was absolutely essential to a first-rate treatment of his life. The 28-year-old Philip Roth, counterintuitively enough, was a wonderful stepfather. Maggie had these two kids — they were emotionally troubled, they were almost illiterate, and he was sweet and decent to them and arranged for them to be properly educated. Parul got all over me because I’m hard on Maggie — Maggie was a disaster, okay? Maggie wrote in her journal about her own wickedness: “I have the mind to reason what is right and wrong but I have no moral repugnance to keep me from anything, but I have [a] huge amount of self-pity where my wickedness keeps me from having the good things that life gives to good girls.” That was Maggie. Philip filled that void. He did what the nice Jewish boy remained to the end of his days would have done. There was a huge mensch streak in Philip.

One of the things that interests me about Roth, and the reason I think he’s a great subject, is the distance between his conception of himself and his reception in the world — something I think he was always playing with. One of the titles for this biography that he suggested to you was “Don’t Step on the Underdog.” This at a point in his career where he was a favorite for the Nobel Prize. Did he truly believe to the end of his life that he still was the underdog?

He didn’t. He didn’t perceive himself as the underdog, his heart went out to the underdog. At a very precocious age, Philip was vehemently against racial prejudice — like Portnoy, he deplored his family’s condescending attitude toward their cleaner. That was the underdog — or the way his father was treated at Metropolitan Life as a Jew. That’s why he wanted to be a lawyer on behalf of the underdog, possibly for B’nai B’rith. But Philip wanted his cake and to eat it too. If you were sick and you were a friend of Philip’s, he would not only visit you in the hospital constantly, he would offer to cover your medical expenses, he would call your friends and try to get them to help. That was a side of Philip. But what he didn’t understand — what he affected not to understand — was that there was also the Mickey Sabbath side. That person that resulted from his, as he put it, “squeezing the nice Jewish boy out of himself drop by drop.” Philip brought this controversy on himself. He was quite capable of sexually objectifying women and making incredibly tasteless jokes about it, which he wrote down in his books. So here we are.

Those kinds of books and those kinds of jokes play differently in 1969 than they play 1999 and 2019. The distance that he’s come in the public conception — whatever the private truth may have been — is great. I’m not the first person to notice that he started his career on panels about minority literature and by the time he died he was considered the epitome of the white male novelist. I’m curious how you think about that, and how much he was thinking about it, how aware of it he was.

Philip didn’t miss a lot. I mean, he wrote The Human Stain — he saw cancel culture coming. He saw the sort of moral absolutism, especially on college campuses, that political correctness was tending toward. He equally disliked the assholes on the left as he disliked the assholes on the right. Toward the end, he lived long enough to see Me Too, and I think it terrified him. He didn’t know what was going to come streaming out of the woodwork. And that’s when he revived the issue of Inga between us, because that had him thoroughly rattled. And he knew what she likely had told me, and if you’ve read my book, you also know what she told me. Philip, whenever he was grousing about the public’s harsh perception of him, even while he was getting all these awards and honorary degrees right to the end, even from the Jewish Theological Seminary, he’s the guy who did a lot of very transgressive stuff and and wrote about it in a way that struck his readers. It’s autobiographical.

As he liked to say, he “let the repellent in.”

He let the repellent in. And that is an aesthetic, I think, that will be his legacy. In a good way. Zadie Smith — who adored Philip, by the way, all these smart women, they liked Philip: Mary Karr, Nicole Krauss, Claudia Roth Pierpont, I could go on — [what she said she learned from Philip] was that literature is not propaganda. Show people as they are. Including yourself.

But as you write, he was asked about Me Too in his last interview, and his answer wasn’t very satisfying to people. Is it a subject that continued to come up between the two of you?

We never discussed Me Too, per se. Certainly, we exhaustively discussed his controversial sex life and how he thought he was perceived because of that. I think he was primarily afraid of Anna Steiger’s friend, whom I call Felicity in the book, coming forward with something. Because he was very aware that Anna Steiger absolutely despises him. So there was sufficient animus for something like that to happen. But the way he expressed his consternation about Me Too was reviving the Inga business and asking to see the transcripts.

There was a Vivian Gornick interview in Bookforum recently in which she was asked about some of the mid-century American writers that were considered great. She said she doesn’t “know one young person who reads Roth, or Bellow, or Mailer — not one young woman anyway.”

I think that says more about Vivian Gornick’s social circle than it does about women collectively.

So you think that that will be the judgment of this particular moment, rather than of history?

Well, I don’t know. Who knows what the future will bring. I am startled by the vehemence of certain reactions to my book, for example. I knew there would be a lot of anti-Roth sentiment out there, and that there are things in my book that would exacerbate that. But I never imagined that I would be implicated as implicitly condoning Philip’s behavior. I don’t see how anyone in good faith can reach that conclusion reading my book. That’s just astonishing to me.

To go back to the reporting process — you trace a number of real people who informed characters in Roth’s work, whether they knew they were aware of it at the time or not. I think you show both sides here: the people who say, “I didn’t want this” and “I didn’t consent to this,” the woman who was the model for Faunia in The Human Stain who calls him screaming and says, “I’m gonna sue you” for stealing my life. You also have Roth saying, they line up for this.

He was being a little puckish, but go ahead.

As you were speaking to them, unmediated by him, how did you see their interest or disinterest in finding themselves in the books? What kind of pushback was there against their fictional avatars?

They weren’t terribly pleased. Alan Lelchuk was furious, and enduringly so, about being the libidinous Baumgarten in The Professor of Desire and the ultimately unsuccessful writer Ivan Felt in The Anatomy Lesson. Maxine Groffsky is a very intelligent, impressive person. She was cordial but firm [when I reached out to her] — she said, “Well, I’d just rather not.” I spoke to people who knew what Maxine’s attitude was toward the whole Brenda Patimkin portrayal, and she was mightily irritated about it. She deeply resented her family being portrayed as these archetypal Jewish suburban Philistines.

Reading the book, and rereading Goodbye, Columbus, I think Groffsky emerges as someone who is fascinating and eminently worthy of her own biography, and maybe she’ll get it, I don’t know — or maybe she’ll write it.

Absolutely. We could go on and on, but we don’t have to, about various sympathetic female characters in Philip’s work that are based on real people. Drenka is another one. Maria Freshfield in The Counterlife is another one. They’re both very intelligent, well spoken, and sympathetic people. But Philip didn’t spare himself in his writing. You know, he gave us Portnoy, he gave us Sabbath. And said outright, for public consumption, through me, “Mickey Sabbath is the most autobiographical character I’ve ever created.” Well, that’s a pretty damning thing to say. He let the repellent in where he was concerned, and everyone else was fair game, too — including his mother, though he denied that.

Tell me a little bit about the material that only you’ve seen, and in fact, only you may ever see: Notes for My Biographer, Notes on a Slander-Monger, and Inga’s memoir of their affair that she wrote for you.

I think you get a sense of the gist of Notes for My Biographer if you read my book; it gives his side of the story vis-à-vis Leaving A Doll’s House. And you can kind of surmise when I don’t quote it outright, when it’s Philip directly addressing that book, it’s probably from Notes for My Biographer. Notes on a Slander-Monger is just his furious ranting on paper.

So these are not exactly great, unpublished Roth works.

Oh my God, no. Notes for My Biographer is polished — it’s copyedited. It was listed on Amazon. It was ready to go. So it’s coherent. But is it a lost Roth gem? No, absolutely not. What’s the phrase that Hermione used? “Relentlessly self-justifying.” Not untrue. Philip wasn’t a deliberate fabricator like John Cheever was. But he saw things through his very subjective lens, and usually it was as an apologist for himself.

I’d like to talk about the Roth canon more broadly, the published Roth canon. Do any of the particular works stick out to you as the crystalline Roth, the archetypal Roth?

Here are my favorite Roth books: Goodbye, Columbus, which he hated. Portnoy’s Complaint. The Ghost Writer, probably my favorite. American Pastoral. And Everyman. And then there are those that I’m very fond of and that I’ll probably reread before I die, like The Human Stain. I also like Indignation, a very underrated book.

I’m also interested in which didn’t stick out to you the first time and later did. I was surprised to read that Roth thought The Breast was particularly worthy of rediscovery.

That’s astonishing to me. I think he thought that it was a sort feminist book — here’s a guy imagining himself as a breast; that guy can’t be all bad. Well, of course, he’s talking about fucking a nurse with his nipple. Kind of a mixed blessing if you’re a feminist. I don’t get his fondness for The Breast, either. I’ll leave it at that.

One thing that doesn’t come up very much in the book is Roth’s influence. Do you see a sort of School of Roth among younger writers?Philip himself recognized that his influence is vague. Because he himself was such a protean human being and writer; he went through so many discrete phases over the course of a 55-year career that comparing a book from one phase of his career with another is apples and oranges. I think what Zadie Smith said gets nearest to the heart of it. That after reading Portnoy, she never again tried to flatter her readership with what a noble African American should be. Philip had gotten in trouble with the Jewish establishment because he kept writing about extremely unsympathetic Jewish characters. He also wrote about sympathetic Jewish characters. It’s a question of voice. I think that there is a sort of ranting loquacity to much of Philip’s work. And I think that we find that, especially in young Jewish writers. I think Jonathan Lethem would concede the influence. And many others as well.

This is The Biography, as the subtitle has it–

That’s pissing people off. It is the biography. Look, Philip’s dead now. No biographer will ever have access to the living man again. All his private papers are under public seal until 2050. I will probably be dead. And many people in my generation. Some of those papers will not even make it to 2050. His family’s gone. I had hours and hours of interview tapes with Sandy, who has been dead since 2009. The people who are alive, and they are a multitude, that I interviewed, they allowed me to speak to them because I had Philip’s blessing, no one will ever have that access again. So I’m just stating a fact that my book, whether you like it or not, will be hard to replicate in its definitiveness.

It’s a defensible point, and I don’t ask you to litigate it. I ask because I’m curious if you have read or will read any of the other Roth books that have come out recently or are soon to come out.

Steve Zipperstein is a serious man. I’m sure he’ll produce a serious work, but it will be more in the nature of a critical biography. Which I think can be safely assumed about Ira [Nadel]’s book too. At some point it’s possible that I will read Steve’s book and Ira’s book, but I’ve had enough for now. And I think I can take a break from Roth, especially after this month is over.