It’s a very human thing to assume that, just because something annoys you, it must therefore be new. Consider the Oscars, which in recent years have been at the forefront of cultural debates over diversity and inclusion, high art versus populism, and what exactly constitutes a supporting performance. This has proven incredibly frustrating to people who remember a more innocent time, a lost golden age when the Oscars used to be all about the movies, man. But many of these analyses leave out one crucial element — the Oscars have always been like this! In fact, those put off by the annual brouhahas around the Academy Awards should find solace in the fact that many of the Oscars fights of recent years are actually reprises of controversies from days of old. Take a look at this voyage through awards-season history (which, among other sources, is particularly indebted to Mason Wiley and Damien Bona’s Inside Oscar) to see just how history repeats.

A Foreign Film Won Best Picture!

Recently: Parasite

But also: Hamlet

Remember that time a foreign film won the top prize and prompted soul-searching about whether the Oscars belonged to America or to the world? Of course, that was in 1949, when Laurence Olivier’s Gothic production of Hamlet won Best Picture. (Olivier, who had just been knighted, also took home Best Actor, so all in all it was a pretty good year for him.) Today, a bunch of Brits coming over and stealing all our Oscars has become a hallowed awards-season tradition. But back then, the Stateside success of Hamlet and fellow British Best Picture nominee The Red Shoes was met with no small amount of grumbling, consensus being that this was no way to treat a wartime ally. As W.R. Wilkerson of The Hollywood Reporter wrote after the ceremony, “Have we a bunch of goofs among our Academy voters who, like many of the New York critics, kid themselves into believing that Britain is capable of making better pictures than Hollywood?” Remarkably similar sentiments would be repeated 71 years later, after Parasite’s big win, by a failed Broadway producer. In both cases, the concern over international bogeymen masked anxieties that Hollywood was losing ground to competition a little closer to home: in the ’40s, television; in the ’20s, streaming and social media.

The Supporting Categories Are Chock-Full of Stars!

Recently: Mahershala Ali in Green Book, Brad Pitt in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, LaKeith Stanfield and Daniel Kaluuya in Judas and the Black Messiah, and more.

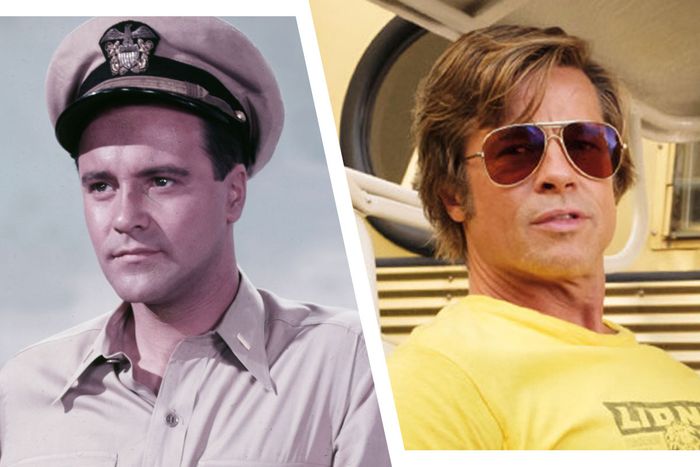

But also: Jack Lemmon in Mister Roberts

Since awards-season gamesmanship usually necessitates not running actors from the same film against each other, it’s common to see performers with a smidge less screen time than their co-stars get bumped down to the Supporting categories — a trend that reached its peak this year when, due to a quirk in the voting results, both of the leads of Judas and the Black Messiah wound up nominated in Best Supporting Actor. The result is that true supporting performances, and the workaday actors who give them, often get ignored nomination morning.

The issue was particularly fraught during the 1955 season, when three-time Best Actress nominee Rosalind Russell rejected Columbia’s bid to campaign her in Supporting Actress for her comeback role in Picnic. But another of the studio’s contracted stars, Jack Lemmon, had fewer qualms, happily taking a secondary role in Warner Bros.’ military dramedy Mister Roberts. His Supporting Actor nomination sparked a fresh round of sympathy for the town’s character actors. “What will become of the many wonderful supporting players who can only hope to qualify in the one category?” a concerned citizen wrote to THR. After Lemmon won, Charlton Heston proposed officially banning stars from the supporting races the next year, to no avail: Three of the nominated men for 1956 were co-leads. Still, there was a silver lining. Though the winner was Anthony Quinn, another star, at least his performance in the Van Gogh biopic Lust for Life clocked in at less than ten minutes.

Snobbish Elites Are Overlooking a Film ‘Real People’ Love!

Recently: Green Book

But also: The Alamo

The Academy’s misbegotten plan to create a “Popular Oscar” was a bad idea, but it did have precedent in Oscar history. In the very first ceremony, there were two Best Picture categories: one for pictures that were Outstanding, and one for pictures that were Unique and Artistic. In a more lasting precedent, the highest-grossing movie of the year, The Jazz Singer, was declared ineligible for either of them. (It was considered unfair for silent films to have to compete against it.) Ever since, awards-season skeptics have complained that the Oscars overlook mainstream hits, a notion that’s become so ingrained that campaigns have occasionally tried to spin it into a winning narrative.

Fed up with what he perceived as the nation’s lax moral standards, John Wayne decided to make a movie about the Alamo, which he hoped would inspire Americans to greatness (and also vote for Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election). Reviews for The Alamo were mediocre, and the film’s massive expense prevented it from becoming a financial success. But Wayne campaigned hard for his labor of love, advertising the production as a patriotic achievement and a massive job creator, and his efforts paid off with a Best Picture nomination. Columnist Hedda Hopper sniffed that, though the film was “frowned on by liberals … I believe it has a good chance of winning.”

Turned out Hopper was the one in the bubble — The Apartment won instead — but a similar campaign angle would play better in the year of the Popular Oscar. Though the Popular Film category died an ignoble death soon after its introduction in 2018, that season climaxed with the triumph of Green Book, a broad, middle-of-the-road buddy movie that rode the upturned noses of the cognoscenti to Oscar glory.

(Another element of The Alamo’s Oscar journey would be accidentally repeated in the 2010s, when Chill Wills’s over-the-top, self-financed Supporting Actor bid found its echo in Melissa Leo’s “Consider” campaign.)

They’re Letting All These New People Into the Academy!

Recently: The post-#OscarsSoWhite swelling of the Academy’s ranks.

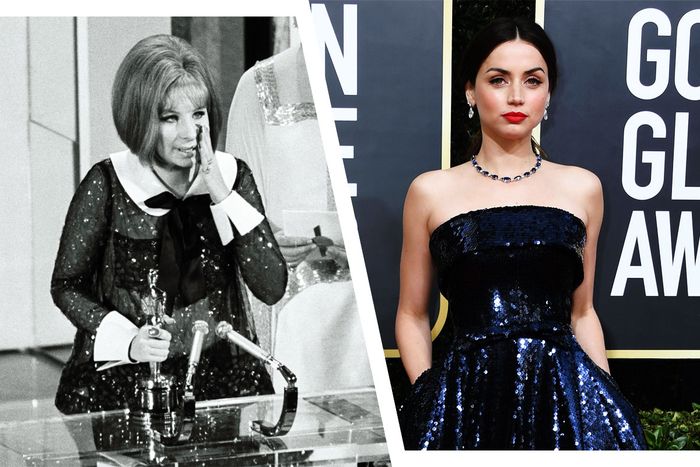

But also: Barbra Streisand’s controversial admission.

Every year, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences replenishes its ranks by inviting new members into the club. The size of each incoming class has swelled in the wake of the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, as the Academy dealt with its diversity issues by inviting as many women, people of color, and international members as it could get its hands on. 2020’s ranks included relative newcomers like Ana de Armas and John David Washington, leading to predictable grumblings about tokenism. But since there were 817 other new invitees, at least the spotlight was spread around. Barbra Streisand had no such luck. Her invite came while she was still filming her debut, Funny Girl, and proved so controversial that Academy president Gregory Peck had to publicly defend her admission. Or maybe she had a lot of luck: In 1969, her first year as a member, Streisand wound up winning Best Actress in a tie with Katharine Hepburn. Wags speculated that she’d provided herself the crucial vote.

This Cancel Culture Is Out of Control!

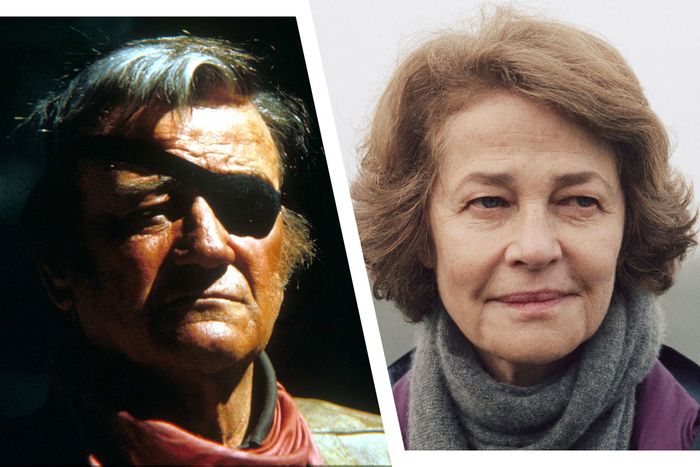

Recently: Charlotte Rampling, La La Land, Three Billboards, Green Book, and more.

But also: Everything that happened at the 1970 Oscars.

The 1970 Oscars should be required viewing for anyone convinced that the culture war began in 2014. The ceremony took place on the front lines of the battle between Old Hollywood and New, as Midnight Cowboy and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid faced off against Anne of the Thousand Days and Hello, Dolly! Once again, John Wayne was at the center of it all. As an outspoken supporter of Richard Nixon and the Vietnam War, Wayne was symbolic of the conservative Hollywood establishment; as the star of True Grit, he was also the Best Actor front-runner. His arrival at the ceremony was marked by a protester holding aloft a sign reading, “JOHN WAYNE IS A RACIST,” and his victory was greeted by boos in liberal households across America. Still, at least he had the good sense to wait until after he’d won the Oscar to give his most famously racist interview, a lesson 2016 Best Actress nominee Charlotte Rampling did not heed.

But it wasn’t just Wayne. The ceremony also saw demonstrations over representation (dozens of protesters slammed Butch Cassidy and The Wild Bunch for stereotyping Latinos as “inferior, incompetent, worthless, and ignorant”) and inclusion (a smaller group highlighted the fact that the Academy orchestra only employed three Black musicians) — all the more surprising because, as everyone knows, those concepts were only invented five years ago by woke millennials on Twitter.

Oscars Speeches Are Too Political!

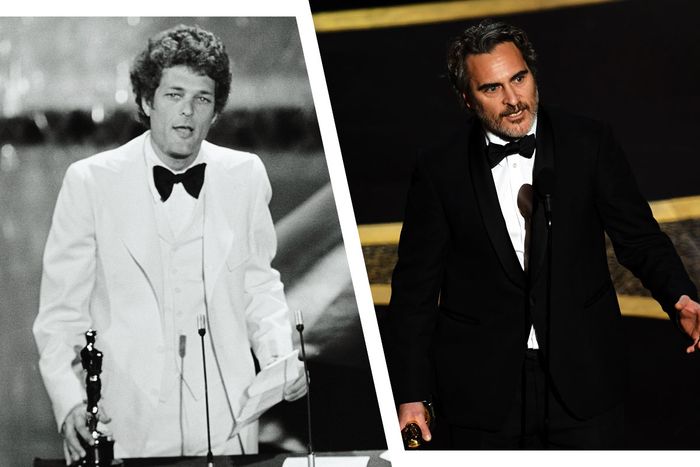

Recently: Joaquin Phoenix’s Best Actor speech.

But also: Bert Schneider’s Best Documentary Feature speech.

The New York Times recently quoted an anonymous Oscars producer who revealed that, according to the show’s internal metrics, “vast swaths” of viewers switch off the telecast once talk turns to politics. (In other words, pipe down about veganism, Joaquin.) The paper presented this as a new conundrum, which might be a surprise to anyone who watched the Oscars during the 1970s, the decade that saw Sacheen Littlefeather accept Marlon Brando’s trophy and Vanessa Redgrave complain about “Zionist hoodlums.”

Less well-known but even more controversial was producer Bert Schneider’s acceptance speech for Best Documentary Feature at the 1975 ceremony. When his anti-Vietnam War doc Hearts and Minds won the Oscar, Schneider took the opportunity to read a telegram from the Viet Cong thanking “our friends in America [in] recognition of all that they have done on behalf of peace.” (The South Vietnamese state would collapse a few weeks later.) Co-host Bob Hope and presenter John Wayne — yes, him again — were furious, and later that night Wayne interrupted the proceedings to read a note from Hope apologizing for the “political references,” kicking off a kerfuffle about which was more inappropriate, the speech or the apology. Compared to all that, Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine speech seems positively tame — at least he kept the Taliban out of it.

Is This a Movie, or TV?

Recently: Small Axe

But also: Scenes From a Marriage

An Oscar-winning filmmaker from overseas returns with an acclaimed work that critics’ groups shower with prizes. But wait! It was originally made for television — can it compete at the Oscars or not? The line was blurry even before COVID-19 disrupted the theatrical experience. Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes From a Marriage was broadcast on Swedish television as a six-part miniseries in 1973 before an abridged version played American theaters the following year, leading the Academy to declare it ineligible. (The yearlong delay was apparently just as much to blame as the TV issue; the French documentary The Sorrow and the Pity had previously been nominated despite also premiering on television.) Even after the National Society of Film Critics gave Scenes From a Marriage Best Film, and A-listers across the industry clamored for the chance to vote for Liv Ullmann in Best Actress, the Academy didn’t budge. “Perhaps all these actresses campaigning on my behalf is more gratifying than the award itself,” said Ullmann, with Nordic equanimity.

Last fall, Steve McQueen’s Small Axe was the subject of similar uncertainty. The five-part anthology was produced by the BBC, but its first two episodes debuted at virtual film festivals. In America it aired on Amazon Prime, which, thanks to COVID-era rule changes, might have made it eligible for the Oscars. McQueen put the kibosh on that: He wanted the project to be considered in toto, rather than as individual films, so for the purposes of awards season, Small Axe would be a limited series competing at the Emmys. But the Los Angeles Film Critics Association paid McQueen no mind — it went ahead and named Small Axe the best film of 2020 anyway.