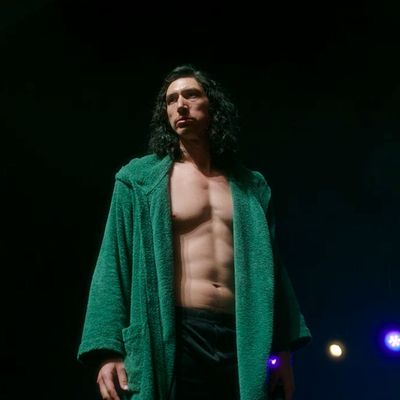

Even people who don’t much care for Leos Carax’s Annette generally admit that it ends well. Which is kind of crazy, since the film ends with a surreal, angry, beautiful duet between Adam Driver’s Henry McHenry, now in prison, and his young daughter Annette (who up until this point has been played by a puppet but is suddenly being played by an actual human girl, the enormously talented Devyn McDowell). It’s a powerful, incredibly well-acted scene. But what the hell does it mean?

As a film, Carax’s Annette is a kind of extreme high-wire act, not so much carefully balancing its way along as dramatically teetering in either direction. And this final scene is in many ways the point at which some of the film’s contradictions are finally resolved. Much of Annette follows the dysfunctional but passionate relationship between Henry and his wife Ann (Marion Cotillard), who seem diametrically opposed both as artists and as personalities. He’s a stand-up who likes to “kill” his audiences with his aggressive, embittered, extremely physical monologues, while she’s a soprano who likes to “save” her audiences with her opera performances, dying gracefully and demurely every night onstage. Then, however, Ann dies in real life, as a result of an accident caused by a very drunk Henry, who doesn’t try to save her after she falls off their boat during a terrible storm. After Henry and Annette wash ashore, the ghost of Ann curses Henry, telling him that she will haunt him forever through their child.

So, over the course of the movie’s second half, Baby Annette serves as a metaphysical vessel for her parents’ conflict with one another — pulled this way and that like, oh, say, a puppet. The child has Ann’s heavenly singing voice, which emerges whenever Annette sees the light of the moon. (Throughout the film, Carax has visually associated Ann with the moon.) Henry, for his part, has been baser in his influence: With his own career in tatters, he’s used Baby Annette the singing miracle child to make money, taking her around the world and soaking up the celebrity that comes with her success. Though he denies it halfheartedly, Henry knows that he’s exploiting Annette. (In Baby Annette’s world, Henry is represented by a pet stuffed monkey she carries everywhere. His stand-up nickname was, after all, “the Ape of God.”)

The push-pull of influence over a child — the way that they often become proxy wars for the parents’ own conflict with each other — is one that many a parent (and child) knows well. And although Annette isn’t really about parenting per se, we shouldn’t discount this idea: By opening the film with a scene of himself and his own daughter (whose mother was Carax’s late partner and muse Yekaterina Golubeva, whose death haunted his previous feature, Holy Motors), the director practically invites us to view the movie at least partly through that dynamic. He also suggests that this battle over the soul of a child has more to do with grief and guilt than just pettiness or control.

Henry has, by his own admission, been seduced by the abyss of rage and contempt. In the film’s penultimate scene, he sings in the courtroom of his inability to feel joy or pride in her voice and success; he was too in love with the darkness that surrounded him to connect with the life-giving power of her art: “Stepping back in time, I’d pull Ann aside / ‘I’m so proud of you, I’m so proud of you’ … I’d say ‘Ann, what brings me the most joy / is to watch you, I’m a small boy / wide-eyed in my awe / at your silken voice / I admire you / Never tire of you … Stepping back in time, I would stand aside, not allow my rage to be magnified.”

As Henry sings to Ann’s ghost, the scene feels almost like a corrective to the earlier duet between them, “We Love Each Other So Much.” (That’s the one where we saw Driver singing while performing cunnilingus.) That song was beautiful, too, but its endlessly repeated refrain of “We love each other so much” gave it an oddly incantatory edge — as if the two were in love with their unlikely love (“counterintuitive, baby”) and not actually with each other. This penultimate number feels like the only time that Henry actually admits to Ann that he sees her and loves her. Of course, by this point, it’s too late; she’s dead and he’s presumably going to spend his life behind bars.

Which brings us to the final scene. Now, Henry is stuck in prison and confronting the child whose life he ruined. But Annette is no longer a Puppet Baby. When Actual Human Annette walks over and takes her place, it means of course that the girl has, Pinocchio-like, finally become a real child. Such symbolism is, of course, painfully obvious, but it works beautifully because Annette has, from its very first scene, embraced the artificial and theatrical. With its color-coded lighting, dramatically unrealistic sets, its superimpositions and rear-projection indulgences, the whole movie has hovered on the thin line between earnest tragedy and playful, self-aware art project.

But now that Annette has been replaced by an actual girl, it hits that much harder when, in the ensuing duet between father and child, she levels accusations against both him and Ann, whose “deadly poison” resulted in her becoming “merely a child to exploit.” Charging in with a furious, adorable bellow, McDowell sings, “I’ll never sing again / Shunning all lights at night! / I’ll never sing again / Smashing every lamp I see! / I’ll never sing again / Living in full darkness! / I’ll never sing again / A vampire forever!”

Henry tries to stick up for Ann — finally! — and tells Annette not to blame her mother for what’s happened to her. It’s a brief moment of selflessness and compassion from a man who up until this point has been singularly focused on himself, on his own triumph and tragedy. He insists that it was his own yearning for darkness that resulted in all this tragedy: “I tried to fight it off / This horrid urge to look below / Half-horrified, half-relieved / I cast my eyes / Toward the abyss, the dark abyss.”

It is here that Sparks’ fondness for wordplay really starts to show itself. Henry has sought forgiveness in his private moments earlier in the film, and he starts to get what he wished for. But forgiving also means forgetting. Annette begins to sing of taking an oath: “Extract the poison from one’s heart / I can’t be sure / Forgive the two of you or not / I took this oath / Forgive you both / Or forget you both / I must be strong.” As his child sings of her uncertainty over forgiveness and forgetting, and their time runs out, Henry embraces her, desperately.

And now, she twists the knife one last time. “Now you have nothing to love,” she sings.

“Can’t I love you?” her father asks, looking into his child’s eyes.

“Not really, Daddy. It’s sad but it’s true,” she sings. Then she repeats the line “Now you have nothing to love.”

Or does she? In fact, she seems to be singing, “Now you have nothing to loathe.” It’s a slight difference. The film’s subtitles still have it as love, but it’s hard not to hear “loathe,” as McDowell extends the word: “loooathhe.”

It’s a startling turning of the tables. And even if the wordplay is merely a trick of the ear, it makes emotional sense. Throughout the film, Henry has never quite been able to distinguish between loving and loathing: He’s leveled contempt at his audience and been rewarded with adoration. He’s been cruel and dismissive toward Ann and her art and been rewarded with her devotion. Like all egomaniacs, his insufferable superiority complex comes entangled with a devastating inferiority complex; ambition and supremacy are matched by self-loathing and anger.

But Annette undoes all that, and in doing so, she undoes him. If she forgives him, she forgets him, and he, a man defined by his bitterness and rage and guilt, will effectively cease to exist. But this is also a liberation. He no longer has anyone to love, but he doesn’t have anyone to hate, either — which includes himself. The shot of him waving good-bye to her as she’s carried away, presumably never to see him again, is as much an existential farewell as it is a farewell to his child. When we see him alone in his cell, he’s wandering slowly, trying to evade the camera. “Don’t look at me,” he mutters.

And then we see one final shot: Baby Annette, the puppet, lying lifelessly on the floor, next to her pet monkey, the symbol of her dad. Both puppet and father have ceased to exist. With one twist of the tongue, Henry’s own child has both liberated him and obliterated him through song.