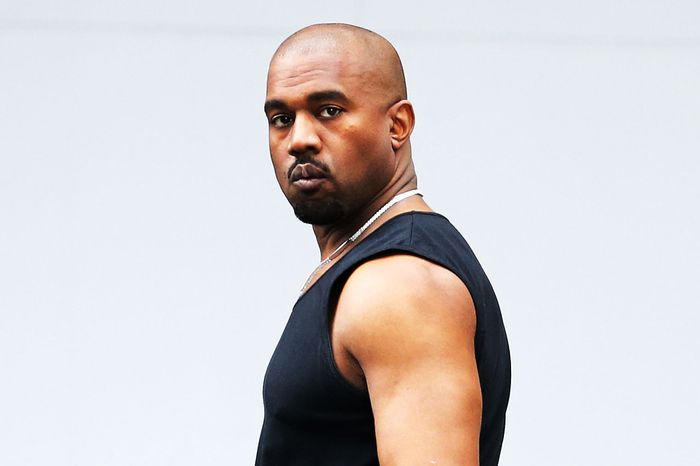

The last hour of longtime Ye insiders Clarence “Coodie” Simmons Jr. and Chike Ozah’s Netflix docuseries Jeen-Yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy offers a rare peek at the artist’s Wyoming workspace operating at full steam. One minute, Ye is listening to beats from 88-Keys and taking a call from Common while Justin Bieber and Dame Dash have a private chat. Later, West is looking at mock-ups of sweaters, shorts, and shackets and inviting Rick Rubin to visit the ranch over steaks. In a corner, behind two Can-Am ATVs, a band works out feels in front of a projector screening Akira Kurosawa’s classic 1957 samurai flick Throne of Blood. As the sun slips behind the azure mountaintops outside Cody, the multi-hyphenate mogul sits next to the mic and freestyles, “You were brought to an inside joke / While my mouth pops back and my insides spoke …” The rap continues a few more measures without any identifiable words. If you’ve been following West’s career awhile, you know he writes raps rhythm-first, working out an attack for the beat before he figures out what the verses will say. If you’ve heard the unfinished demo versions of tracks like Yeezus’s “Black Skinhead” or Jesus Is King’s “Everything We Need,” you know these songs benefit greatly from the extra editing and refinement. For West, this process is the difference between a promising mess and a poignant message.

But since 2010’s G.O.O.D. Fridays — when Ye dropped a new song each week, and the pressure it created seemed apparent in little mistakes in songs like “So Appalled” — he’s been recording under tight deadlines, making music while he tends to other business. Half of the vocals for Yeezus were recorded in two hours while West waited for a plane to Milan. 2016 saw Yeezy fashion endeavors dovetail with the launch of The Life of Pablo and one-sided beef with Wiz Khalifa. 2019’s Ye was created two weeks before release when the artist scrapped a whole album and started over again, hashing out the lyrics in eight days. Last year’s Donda made a public spectacle of its creator’s mercurial, last-minute bolts of inspiration, treating crowds to three iterations of the album in progress. From one event to the next, polish brought out the potential in songs like “Hurricane,” a great performance from Lil Baby couched in placeholder vocals from Ye until the hook from the Weeknd came in. New tracks appeared and vanished. Lately, Ye releases don’t feel baked all the way through, though. Updates to new albums raise the question of whether the product is finished at release. Fans have adopted the language of video-game developers as mixes are tweaked and “patch notes” are circulated. Hastily reworked albums and promising songs left on the cutting-room floor hurt the dependability of an artist whose catalogue once challenged the greatest in hip-hop. We used to hear stories of legendary sessions where West, taskmaster and perfectionist, pushed collaborators to greatness they hadn’t believed possible and matched their achievements with his own. Now, we pay to play his demos.

What even is Donda 2? Is it the divorce album where West taps into the depressive gloom that animated 808s & Heartbreak as he surveys the fallout from Kim Kardashian leaving him? Is it the “living, breathing, changing creative expression” he’s been threatening to sell us since he fiddled with The Life of Pablo for weeks after it landed on Tidal? Is it a scheme to disrupt music streaming, to remove the middleman and seek direct access to data from big spenders that support Ye, or a stunt to monetize Donda-era leftovers by hosting Donda 2 exclusively on the STEM player, the $200 portable audio player and remixer created in collaboration with London-based tech start-up Kano Computing, which counts West as an investor? It’s hard to know what the intent here is because West is clearer and more concise in his messaging on social media than he is within the confines of his own album. You think Donda 2 will unpack the breakup drama as “True Love,” “Broken Road,” and “Get Lost” each share downcast observations about wounded pride and the stresses of shared parenting, about how it feels to have to ferry the children back and forth between households. But a long stretch of open beat at the end of the first song seems like a spot where a second verse might normally go. The second song, “Broken Road,” comes in hot — “Baby I’m free, baby I’m free, like a homeless person” — but quickly fades. The third cut sets a pace the album maintains: “Get Lost” speaks glumly to emptiness and despair, but only if you’re able to make out what is being said.

You can argue that the murkiness of the words in “Get Lost” is intentional, a kind of aesthetic performance of inner confusion and turmoil. But the patchiness of Ye’s performances over the next dozen songs can’t be chalked up to production choices. A lot of these tracks simply aren’t finished, and it’s jarring hearing a stellar guest verse next to the marquee artist’s rough drafts. The triumphant “We Did It Kid” takes off with a spirited verse from Baby Keem and closes out on Migos trading madcap punch lines, but not before the beat drops out and West contributes a few quick lines of mostly gibberish: “Ba da da, everything that we planned!” On “Pablo” and “Happy,” he’s joined by Future, Donda 2’s executive producer, who smokes him again and again. While Future’s verses are streams of powerfully evil boasts — “Trappin’ in Atlanta / Bought three, four, five Phantoms / Drug dealers, murderers, and the scammers / Crocodile Birks for your mama” — Ye struggles to find his flow: “Run up on the son when I’m in it / Tinted, squinted, minute, dunno, then a, minute.” (Donda 2 originally featured a third Future team-up titled “Keep It Burning” where almost every one of West’s lines contains a nonverbal utterance or two, but that one was pulled. It behooves any hip-hop head who spent any part of the last decade grousing about “mumble rap,” and who can be found fussing about the diction of Detroit and California rappers in 2022, to check out Future rhyming alongside actual mumbling for a clinic in the difference between heartfelt lyrics delivered through a regional drawl and a person not actually using identifiable words in their verses.) Jack Harlow tries to save “Louis Bags” after West flames out attempting to parlay a pointed hook — “I stopped buying Louis bags after Virgil passed” — into a message about keeping money in the community, a shame since the writer of “All Falls Down” and “New Slaves” rarely has trouble voicing frustrations about navigating the fashion industry as a Black man.

To get why West, who used to call himself the “Louis Vuitton don,” is mad at LVMH, you’d need to know he was hurt when the brand hired Virgil Abloh as artistic director in 2018 but didn’t reward West for the networking he’d done alongside his late friend. (“I didn’t do one collaboration,” Ye recalled in a recent Facebook discussion titled “Controlling Our Narrative.” “I was just there for the hug and the cosign. And it frustrated me … ’cause we fought for that together.”) To understand why Universal Music Group chairman and CEO Lucian Grainge catches a stray in the XXXTentacion collaboration “Selfish,” you’d need to have kept track of the G.O.O.D. Music founder’s demands to be let out of his record contract in 2020, when he called the UMG exec a “non-billionaire employee.” Grasping all the threats and provocations in “Security” requires knowledge of West’s war of words with Saturday Night Live star Pete Davidson. To know why the comic is a perfect vessel for the rapper and designer’s ire, it helps to know what 2009 sketches led him to say, “Fuck SNL and the whole cast” on that year’s “Power,” and which sketch from Pete has West fuming now. (“Ain’t no shame in the medicine game! I’m on ’em! Take ’em!”) The record feels more like a tie-in to the drama than a cohesive statement from an auteur like West. At its most coherent, Donda 2 is a rebuke for anyone getting between Kanye and someone or something he wants. It was a thrill, in much less turbulent times, to watch him bulldoze through naysayers. He spoke to and for the everyman. His success was inspiring. A rising tide lifts all boats, we thought. But that didn’t happen. American billionaires became a de facto oligarchy, their tantalizing jet-set lifestyles forever out of reach for anyone lacking the necessary venture capital, a disparity exacerbated by financial hardships brought on by COVID. It is into that scene that Ye presented himself as an outsider presidential candidate campaigning on a platform of faith-based theocratic conservative rule and floating the idea of paying women a million dollars each for opting out of abortions.

West has not yet gotten over the decidedly negative response to his presidential bid, and the animosity he harbors about the 2020 blowback bleeds into everything. It’s there in Wyoming at the end of Jeen-Yuhs, where Ye still has “2020” shaved into his head. It was parked at the Drink Champs table where he implied that a number of close friends were just puppets of the Democrats, where he said he used his conscious rap friends for clout in the early 2000s, and where he revealed that one of his biggest career regrets was signing Big Sean, one of G.O.O.D. Music’s most reliable commercial draws. It’s there in the bullying of Pete Davidson, “Hillary Clinton’s ex-boyfriend,” as Ye alleges. It created major tension with Kim. But rage doesn’t honor Donda or God. It doesn’t smooth anything for Kanye. Between the growing library of songs with men with abuse and assault cases and allegations, the sharing of private texts with Kim, and the weaponizing of the fandom to harass Kim and Pete, the impulses there are shortsighted and unwise. You’d think Ye would own up to being unreasonable in a song called “Selfish,” as “Runaway” did, but that isn’t in the cards for us: “Lewinsky / Treat me likе the president / Don’t look at me / Like I need medicine.”

Ye thinks we should have the power to shift our public perceptions. (He says he feels like a “prisoner of a concept of a narrative that people put on me to get you guys to not pay attention.”) He uses this power to post videos where he kidnaps and buries Pete, and captions celebrating running the guy off of Instagram. It’s toxic behavior, retrograde thinking, poor use of a massive platform. (What message does this impart to followers? That men can date around, but women can’t? That wives belong to their husbands forever?) It can’t be easy navigating bipolar disorder in the middle of a high-profile celebrity divorce when your private mental health has been the subject of much intense speculation. But it is unfair to try to pin his flaws on a diagnosis while attributing his triumphs to business acumen. It demonizes mental illness by implying that irritable behavior like targeted internet harassment is merely a natural manifestation of the disorder and not a choice made in agency. Ye isn’t wrong to want to have a say in the way he is seen by others, but what he really wants is the freedom to say what he likes without being called to the floor for it. The negative headlines would stop the moment the negative behavior did. Ye could flex that power today.

Anger is the root of Donda 2, but the record doesn’t try to frame the experience in a manner that makes it accessible to non-billionaires, and it doesn’t push the music anywhere new, preferring to tap the expected regional pressure points, leading to quirky lyrics like the one in “City of Gods” about wearing Balenciaga boots with a Yankee fitted. Donda 2 revisits every idea its predecessor did, this time to dwindling returns. As with last year’s album, the minimalist moments excite — like “Lord Lift Me Up,” where Donda MVP Vory sings over a slice of strings pulled from Alabama soul singer Sam Dees’s “Just Out of My Reach,” and the beat comes out sounding like something you might hear in a William Basinski or a Stars of the Lid album. But the impulse to keep these songs airy can make them feel slight. The thinness of “Flowers” evokes the enticingly skeletal production of Donda’s “Junya,” but the newer song doesn’t hold up. The lyrics are there but the music feels empty, unable to match the last album’s intriguing balance between spaciousness and hollowness. The stems bear out how little is there, presenting an intriguing test case for a gadget that lets you carve a track like a chicken. Finishing all the lyrics wouldn’t make these songs seem less like gilded, untouched rooms in a mansion. There isn’t much precedent for an artist at Ye’s level selling music this far from sounding done or for tying the release to $200 personal electronics. Nipsey Hussle sold mixtapes for $100, but they were not half-baked; U2 annoyed everyone forcing Songs of Innocence onto iPhones, but it didn’t come with any unmixed vocals or unwritten verses. Maybe Donda 2 will make history, and maybe it’ll be remembered as a ledger of personal slights, a burn book for the billionaire boys’ club. One wonders what West made of Throne of Blood, Akira Kurosawa’s samurai Macbeth adaptation, back in 2020. Did he see himself in the story of General Washizu, a warrior so ruthless in his quest for more power that his own army turns on him? Does Kanye feel boxed in by fate? Does he know he doesn’t have to go out that way?