“You’re not too smart, are you? I like that in a man.” When Matty Walker — played with haughty insouciance by Kathleen Turner in her very first film role — tosses these two lines over her shoulder to the leering lawyer Ned Racine (William Hurt), he should have known his days were numbered. This isn’t a pass, it’s a warning. But he’s too horny, too dumb, to see it for what it is.

In Lawrence Kasdan’s directorial debut, the 1981 erotic thriller Body Heat, Matty and Ned meet on a blistering night. The kind that requires you to roll ice cubes down your body while sitting in front of a fan. The kind with air so thick it makes your hair stand on end and your skin perpetually slick. It’s not like the heat is anything the people populating Miranda Beach, a fictional South Florida seaside town, don’t understand, but this is different. It’s as if Mother Nature herself is foreshadowing the hothouse dynamics soon to come.

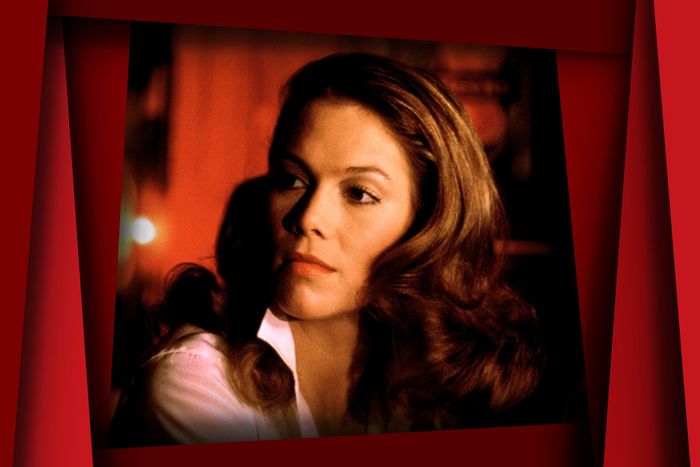

Dressed in a tailored white dress that flutters upward with the breeze, giving a view of legs that go on well beyond the horizon line, Kathleen Turner is utterly, undeniably devastating. “Miss Turner is brand new to films, and her only problem may be that she’s too conventionally beautiful in her classy, dark-haired way to register immediately as a film personality,” Vincent Canby wrote in his review of the film for the New York Times. But to home in on her beauty is to miss the actual bravura of her performance, her understanding of what the camera desires, and her kinetic intelligence as an actor. It’s to miss how her work in one of the earliest erotic thrillers resurrected the femme fatale of classic noir in new, perfectly lascivious ways.

The story situates Matty as a smooth and cunning figure, several miles ahead of Ned’s venal legal mind. This gives a certain edge to their early flirtations on the boardwalk after he spots her leaving an outdoor classical-music performance. He throws out the kind of tired lines that work on women very unlike Matty — working-class women whose dreams come to life during that sliver of time before the end of the night and the start of another grueling day. Pleasure for these women is in short supply, but for Matty, pleasure isn’t negotiable. Ned catches on by virtue of her demeanor and appearance that she isn’t from Miranda Beach at all. She’s moneyed and living in the nearby, upscale Pinehaven. After she spills a cherry-red snow cone on her dress, Ned offers to get her some paper towels and Matty raises her voice, all whiskey and honey, above the fray of the crowd: “You don’t want to lick it?” When she eventually disappears, Ned remains determined to find her. Wouldn’t you?

Still, the line that snags me is the one from the beginning: “You’re not too smart, are you? I like that in a man.” It’s the kind of biting remark you can imagine slipping from the lips of dozens of previous femme fatales. There are obvious points of comparison for Matty, particularly Phyllis Dietrichson, played with icy malevolence by Barbara Stanwyck in Billy Wilder’s 1944 noir Double Indemnity, a film that set the template for not only Body Heat but all noirs created in its wake. In writing about Body Heat, the legendarily caustic critic Pauline Kael criticized Turner’s performance, describing the actress as “following the marks on the floor made by the actresses who preceded her.” It’s exactly why I think Turner’s performance is so dazzling and rich to study. In Matty you can find the yearning of Lana Turner’s Cora in The Postman Always Rings Twice, the smoky grace of Lauren Bacall’s Marie in To Have and Have Not, the determination of Bette Davis’s Leslie in The Letter, and the barbed wit of Gloria Grahame — the actress who most exemplifies the noir genre — in Crossfire, Sudden Fear, and In a Lonely Place. (Grahame, who understood her body and how it could be weaponized, is perhaps the best actress to ever slink into a noir.)

But Matty possesses something else: real, palpable, fulfillable lust. She doesn’t just use sex and seduction as a weapon; she actively desires it. Erotic thrillers, after all, owe a lot to the abolishment of the Hays Code, which prohibited things like overt sexual behavior, explicit scenes of passion, adultery, complete nudity, and sexual hygiene from appearing onscreen before the strictures completely dissolved by 1968. In the Hays Code era, criminals were punished or rehabilitated by a movie’s end, and so the conniving femme fatale rarely made it out alive or intact. But relieved of these restrictions in the ’80s, erotic thrillers could remix and reimagine the nacreous qualities of noir, still punishing men for their horned-up ignorance but letting the femme fatale succeed at something she hadn’t done previously: survive. She wouldn’t just outsmart and outmaneuver the men in her orbit; she could out-fuck and outlive them now, too. (Though she would remain, primarily, white. Black women and women of color in general rarely appear as femme fatales in American erotic thrillers. For that, you’ll need to look beyond the shores of the U.S., particularly to South Korea, where the genre continues to bend, evolve, and flourish.)

It is easy to view the femme fatale both in her original incarnation in the 1940s and her renewal within erotic thrillers beginning in the 1980s and ’90s as, film theorist Elizabeth Cowie put it, “a particular masculine fantasy” in which “sexual difference is played out.” It is even easier to critique Matty as the product of the male gaze, as hollow as that term can be when it centralizes the efforts of male directors and ignores the women like Turner who had a hand in bringing their characters to the screen. The ideas powering the proliferation of the male and female gaze in modern criticism narrow the lens through which we consider women’s images onscreen, solidifying a gender essentialism that at once reaffirms the very heteropatriarchal dynamics these critics want to critique and ignores the ways marginalized folks — the queer and people of color amongst us, especially — interpret the dynamics that we see onscreen, finding texture and yearning such critical terminology doesn’t take into account. So, while it has been forcefully argued the femme fatale was born of male neuroses and fantasies, her ability to appeal to other fantasies along her historical arc ensured her longevity. The actresses who bring these characters to life — like Turner, who created a blueprint for Linda Fiorentino in 1994’s The Last Seduction and Jennifer Tilly in the lesbian noir mélange of 1996’s Bound — understand this appeal.

Importantly, their femme fatales aren’t meant to reflect women’s real-life struggles, nor do they. As writer Michael Boyce Gillespie has noted, film is a poor mirror. In the most memorable cases, femme fatales like Matty complicate the fictional image of women to which we’ve become accustomed, and Turner’s penchant for complication is best gleaned in rewatch — knowing what Matty’s capable of in Body Heat (deliberately invalidating a will, inquiring about building a bomb, deluding Ned into thinking their beach meet-cute was serendipitous), you’ll question every line, every gesture, every glance that she makes. The second time you observe their meeting in a cherry-red-lit bar, you can see that she’s playing a role fit to Ned’s desires, her body and voice — willing and breathless — working in concert for seduction. Later, as she watches Ned circle the windows of a home she’s locked him out of, her breathing grows quicker, yet her gaze never leaves him. He breaks the window with a chair — sex and violence, the markers of erotic thrillers — and they embrace, enraptured. Turner doesn’t play Matty as simple. She’s in love and lust, but neither emotion quite supersedes her financial motives. She’s in a constant state of desiring.

Good performances are typically graded on standout moments: a lengthy monologue, a well-crafted accent, a moment of ecstasy rendered physically. But Turner’s performance has no single, remarkable scene. It is a great performance by way of accumulation — in which her husky voice, elegant physicality, and minute gestures add up to a portrait of a woman whose interiority is forever beyond your reach. Turner is performing Matty who is performing Ned’s desires; we will never truly know who she is or how she sees herself, but Turner is sly enough to let the cracks show. When Ned unexpectedly bumps into her at a restaurant with her mob-connected husband, all three of them have dinner. For the first and only time, Matty is nervous. (She’s also styled dramatically differently than how she typically appears with Ned, her hair wrapped up daintily and her dress more prudish.) Turner turns a slim silver lighter between her fingers over and over again, even as her eyes and voice have a lightness to them. She’s straining.

The film ends with her achieving her dream: rich on her own and living in some faraway, beautiful land by the sea, miles from the South Florida grime and the mistakes that shadowed her life leading her on this path of false identities and truculent manipulations. But what’s curious is she doesn’t look ecstatic or pleased. There’s no wicked smile on her face. Instead her gaze is inscrutable, like the woman herself. Is she feeling guilty over her misdeeds? Is she pondering the life she can lead going forward? Is she thinking of the husband she had killed? Is she considering the man she doomed to prison? In the hands of Kathleen Turner, anything could be true.

More From This Series

- 36 Erotic Thrillers You Can Stream Right Now

- Margaret Qualley and Christopher Abbott on Their Dominatrix Thriller

- When Lindsay Lohan Was the Best Part of a Paul Schrader Movie