Twenty-five years ago, Paul W. S. Anderson released one of the gnarliest, most unforgettable science-fiction horror films ever made, but it took most people a few years to realize it. Starring Sam Neill, Laurence Fishburne, and a spaceship that had just returned from a journey through Hell, Event Horizon came out in August 1997 and bombed with critics and audiences alike. (Those of us who were fans of the picture back then can tell you how lonely an experience that was.) But over the years, Anderson’s film grew in reputation. This was due partly to the indelible quality of its imagery: its brief but deliriously grotesque glimpses of Hell, the medieval-torture-device-like design of its titular spaceship, not to mention a final act that featured a mad Sam Neill running around naked and on fire after gouging out his own eyes. (“Where we’re going, we won’t need eyes to see.”) Anderson understood how to shock audiences — maybe too well, since members of his studio were notoriously outraged when they first saw the film — but Event Horizon carries a fascinating cautionary tale about our inability to let go of the past, a tale enhanced by a cast that brings real depth to what might, on paper, have looked like fairly disposable genre work. On the occasion of the movie’s release in a special 4K edition from Paramount, I talked to Anderson about the endurance of his now-classic film.

When Event Horizon first came out, it didn’t do great business and was savaged by critics. It has been nice to see it find its audience over the years. How do you think that happened?

I think some of the things that hurt us as a theatrical release back then have been our saving grace in terms of building a cult audience over time. First, the movie has a very downer ending. It doesn’t tie everything up in a nice, neat bow at the end. A lot of audiences — they like certainty. They like to know exactly what happened. But Event Horizon doesn’t do that. Is Joely Richardson insane? Is Sam Neill really there? It’s unsettling. And it gives people a lot to talk about. Did they really go to Hell? Was it just a dimension? And that classic haunted-house question: Is the Event Horizon really haunted or is it the people who are going there that are bringing their own haunting? Are they the ones haunting the house or is the house haunting them? As a cinemagoer, I like being able to discuss the movie afterward. But I think maybe that hurt us theatrically the first time out.

I will say, one of the things that has helped it hold up over time is the advice I got from Richard Yuricich, who was my visual-effects supervisor on the movie. He’d worked on 2001, Blade Runner, and all these amazing movies that, when you looked back at them, you went, “Wow, they still look amazing.” I said to Richard, “How did you do that?” And he said, “Well, just do everything as real as you can possibly do it.” That was his approach. If you can build it, build it. Rather than having Laurence Fishburne in front of a blue screen, why don’t you build the set upside down, dangle him from a wire and spin him round and round, and spin the camera around while you’re doing it? It’s a lot more difficult, but boy, does it look good. All we had to do was wire removal. And it’ll never date, because it’s real. That was his advice. I followed it. I ended up with a movie that even now, because there isn’t a huge amount of CG in it, I think still looks terrific.

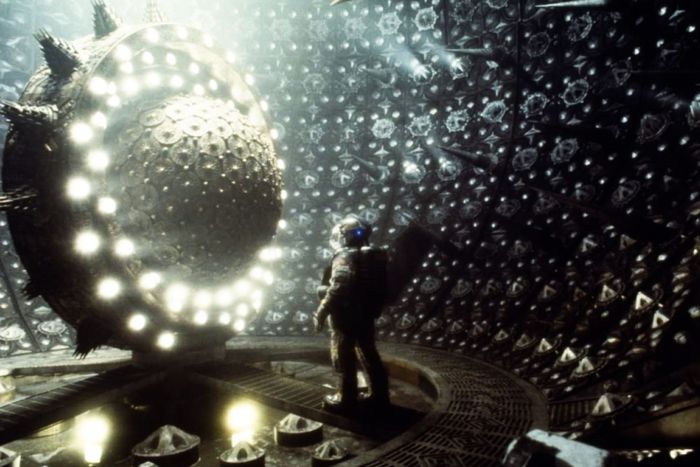

So, something like — I don’t even know what to call it. The core? The gravity drive? The, uh, giant rotating thing?

The Third Containment, I believe it was called.

That. Did you build that actual thing — at that size?

You bet I did! And you should have seen the looks I got from the construction manager in England when they looked at the plans for the drawings and I said, “I want to build it.” They’re like, “Really?” And I said, “Not just that. I want it to move.” They’re like, “No, that’s insane. You can’t do that.” We built it, and it moved, and it looked fabulous, and it still looks fabulous 25 years later.

One of the best openings of any movie, I think, is Blade Runner, where you see the reflection in the eye of the flame, then you see the cityscape. I talked to Richard: “Why does it look so good?” And he said, “Well, because we built it. That’s why those visual effects look good. They’re all models.” So that’s what we did. When we could build it, we built it. For the spaceships, obviously we can’t build full scale, but we built big models. Thank God we didn’t go CG. Because at that time, CG was around. Jurassic Park had just happened. There was definitely the option to build all the spaceships in CG. It would’ve been a lot easier, but the movie certainly wouldn’t be holding up right now. In fact, it wouldn’t have held up a couple of years after its release. Because nothing dates faster than cutting-edge CG.

When I last talked to you, you reminisced about how when you took the Mortal Kombat job, you didn’t know anything about effects, but you lied and pretended that you did. Then you had to give yourself a crash course in special effects to make that movie. What was the learning process for you on Event Horizon?

Ironically, by the time Mortal Kombat was finished, I went from being one of the directors who knew the least about visual effects to probably one of the most experienced visual-effects directors in Hollywood. Because a lot of directors don’t go into the visual-effects companies and work with the individual artists — they wait to be shown the shots, give some notes, and don’t get into the nitty-gritty of it. I feel like my work has benefited from that since then.

On Event Horizon, I would say the big thing I learned was about actors. I was very fortunate that I worked with a terrific cast of actors who were very, very giving. Laurence Fishburne had worked with the best directors. There’s an actor who could have gone, “Ah, what does this kid know?” But he didn’t. He was very, very kind; so was Sam Neill.

That’s another thing that I think distinguishes Event Horizon from other sci-fi films of the era. It’s surprising to see these actors in a movie like this. Was it difficult to convince them to do it?

They were excited to do it. Because I was casting them against type. Fishburne was written as a Texan cowboy in the original script. When we offered him the role, he’s like, “Oh, this is interesting. I haven’t done a movie like this before.” Sam Neill, at that point, was the guy who saved the kids from the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park. He was right up there with Tom Hanks as the person you would most trust your children with. The idea that he would then play this man who starts rather benevolent, then becomes this psychotic creature who tears out his own eyes — he loved that.

Then there are other actors like Joely Richardson, who was very much a kind English rose at that time who’d done lots of acclaimed historical fiction and art movies. She’d never been in a movie where a tank of blood burst behind her, she had 50 gallons of blood douse her, and she was wrapped in barbed wire! I was putting these actors in a very different environment, and I think they really liked that.

I always think of Sam Neill’s character going basically crazy at the very end. But every time I watch the film, I’m reminded that it’s a gradual progression. You see early on that weird obsessive quality of his. He’s already a little off.

I think if you rewatch the movie, he’s pretty crazy at the start. I mean, he hasn’t gone crazy, but he definitely has the potential to. Because one of the great jumps in the movie is where he’s shaving at the start. He’s alone in his room, but he’s looking at the photographs, and the way he holds the razor to his face — the audience are on edge. When the blinds go up, obviously they’re jumping, because it’s an abrupt cut and there’s a big sound, but they’re ready to jump, because he’s delivering something a little unsettling. Something’s off about this guy.

Location and setting tend to play a big part in your films. Was there always a strong sense of place in the script?

Oh, it was always a haunted-house movie. That was in Philip Eisner’s original screenplay. The nature of the haunted house was something that I brought — the idea of doing this Gothic-inspired creation. The movies that had really inspired me in space were Alien and 2001, and they both have such great inception points in terms of their look. For 2001, they had all that research they did with NASA as to what it would really look like. On Alien, Ridley Scott had the genius stroke of employing H. R. Giger. So he got one obsessive man’s creativity that distilled down into this biomechanical creation. You look at Giger’s art books and it’s the Alien spaceship. It’s the alien. It’s already all built in there. I thought, Well, I don’t have NASA, and I don’t have Giger. What do I have? Because if I go into space with no ideas, we’re just going to do some generic corridors. I need a strong inception point.

I was in Paris looking at Notre-Dame cathedral, and I thought, that’s it. If you want a haunted house, Notre-Dame is one of the best examples of Gothic architecture in the world. It was meant to scare and intimidate the populace with the importance and power of God. So we scanned Notre-Dame cathedral into a computer, then broke apart the constituent elements and built a spaceship out of it. I said, “We can’t build anything that isn’t in Notre-Dame.” So the flared pillars that you see inside the spaceship — these are Gothic flare pillars, and they were built that way to help support the weight of these structures. The antenna dishes on top of the Event Horizon are all based on the gargoyle clusters on the top of Notre-Dame. The intricate steelwork is all based on the designs of the stained-glass windows. The thruster pods of the Event Horizon are the towers of Notre-Dame cathedral turned on their side, and the cruciform shape of the Event Horizon itself is the cruciform shape of Notre-Dame cathedral from plan elongated a little bit. I think that discipline to build it from those elements gave us a really original look. You don’t think about it, but subliminally it’s there.

I understand that postproduction was quite abbreviated on the film.

Well, traditionally as a director, you get a ten-week director’s cut, then there’s usually like four or five weeks of studio and producer notes. So you are really editing for 14, 15 weeks before you eventually put a movie in front of an audience. Paramount was producing Titanic with 20th Century Fox, and it was supposed to be a big summer movie. Then, rather late in the day, James Cameron told them, “You can’t have it for summer. It’s going to be Christmas.” My movie was supposed to be in the fall. It’s a scary movie, Halloweeny. That would be the appropriate release time. But suddenly, Paramount didn’t have a movie for the summertime. So I was it: “You’re going in the summer!”

A more experienced filmmaker may have fought against that, going, “Wait a second. You’re not releasing my dark horror movie in the middle of summer.” But it was only my third movie and my second studio movie. And I’m like, “Oh, really? You want to release me on all those screens in the middle of summertime up against a Harrison Ford movie? Great! That sounds like you have a lot of enthusiasm for my film.” Now, when I look back on it, it was like the Charge of the Light Brigade: We never stood a chance.

We only got four weeks to cut the movie after we wrapped principal photography. And what made it even worse was that there was another week of second-unit shooting, and I was directing the second unit. So I was working during the day, and I could only edit at night. Really, I only had three weeks to cut the picture. The end result was we showed the movie and it really wasn’t ready to be seen. It was too long. I hadn’t had a chance to refine it, so it didn’t test particularly well. I don’t think it was ever going to test well, because it had a bleak ending. I’m sure you’ve seen those test cards that people have to fill out. “Would you rate the movie ‘Excellent,’ ‘Very Good’?” A movie that ends the way Event Horizon does — it’s so bleak. You’re never going to say that was excellent, because you feel like people will judge you: “If you really love that, you’re a sick person. Did you see the intestines and the stakes shoved through people and the eyes tearing out?” Right after Mortal Kombat, New Line released Se7en, and I know they were not confident, because that had tested badly. Gwyneth Paltrow’s head in a box — that was never going to get good test results.

So we didn’t get great test results. The studio — they were supportive, but you could see they were panicked. They were horrified, because they saw all this graphic imagery that I realized they hadn’t seen before. We were shooting in London and sending the dailies back to Los Angeles. But I think they were watching the main-unit dailies. All of those visions of Hell that were so striking were being shot by me at the weekend directing a second unit. I think at that point, studios didn’t bother watching the second-unit stuff. When they saw it for the first time with an audience, they were horrified. I remember a studio executive telling me, “But this is the studio that makes Star Trek!” It was like I was besmirching the good name of Star Trek by making this horrible movie out in space.

We ended up with a movie that I’m very, very proud of, but I think there’d probably be a slightly better cut of it if I’d had the whole ten weeks to perfect it.

Over the years, there have been efforts to find previous cuts. And I know there are deleted scenes that are extras on the 4K release. Is that search still ongoing to find some of the other material?

We have found deleted stuff, but it only exists on VHS cassette. It’s not the quality that you should have to reinstall it back into the movie. Event Horizon was made right before the DVD boom. We were in the last year of VHS and laserdisc, where you could only fit the movie on the VHS. On a laserdisc, if your movie was really long, you needed multiple laserdiscs just to show the movie. So there wasn’t that hunger for all of that behind-the-scenes stuff, deleted scenes, special editions. When Event Horizon started developing this cult audience, by that point it was too late. The studio had thrown a lot of the stuff away, because they didn’t archive it. They didn’t feel there was any need to.

Whose idea was it to have the guy holding out his eyeballs? Because that is still one of the most searing images I’ve ever seen in a film.

I can’t remember, to be honest. It might have been in Philip’s original screenplay. I might have come up with that piece of sickness. I’m not quite sure. I’m glad you remember it. I think, ultimately, the one thing that the postproduction process did do was, because the studio was hard on me with how graphic the movie was, it made me cut stuff really fast. I think that was a good decision, because if I’d been able to indulge in the graphicness of it, I don’t think it would’ve been as effective. You see it in these one- and two-frame cuts, where you don’t show the audience too much and they imagine a lot. I can’t tell you the amount of people who’ve approached me and said, “Oh, that image from your movie,” and they describe these terrible images that I never shot, but they somehow have imagined that they’ve seen them in my film! Nothing scares people more than their own imaginations.

This interview has been edited and condensed.