In the 1948 children’s book My Father’s Dragon, a boy named Elmer fights with his mother after caring for a stray cat, and then runs away to the fantastical Wild Island to find a dragon and learn how to fly. He meets lions and tigers, a rhinoceros and a gorilla, and helps solve the animals’ problems with items from his knapsack — chewing gum, magnifying glasses, a rubber band. Then he frees the dragon from its servitude to the island, and they fly away together, the end. It’s a simple story charmingly illustrated, and screenwriter Meg LeFauve and director Nora Twomey adored it. The two began discussing how to adapt it back in 2008, but to appeal to audiences of all ages, as LeFauve’s Inside Out and The Good Dinosaur and Twomey’s The Secret of Kells and The Breadwinner had, My Father’s Dragon needed a second act.

“There was a particular page that really struck me: where Elmer is giving a saucer of milk to an alley cat, and his mom gets angry with him. I just thought that there were so many layers to that moment,” says Twomey, co-founder of animation studio Cartoon Saloon. “It really struck me, having been a child who looked up to my parents’ eyes at times, realizing that they’re not telling me the whole truth, and that I probably couldn’t deal with it anyway.”

That push-pull feeling of wanting more responsibility, yet feeling uncertain of whether you’re up to the task, is the backbone of My Father’s Dragon. Human boy Elmer (voiced by Jacob Tremblay) and young dragon Boris (voiced by Gaten Matarazzo) become friends when Elmer frees Boris from enslavement on Wild Island, then butt heads over how to save the island from sinking. In classic Cartoon Saloon form, the film (now streaming on Netflix) is visually playful, mystical, narratively ambitious, and slightly melancholy. It thoughtfully considers the heroism we expect and provide to our friends, our family, and ourselves. Here, LeFauve and Twomey — who agree that “every movie is a coming-of-age movie” — break down three scenes that best illustrate the movie’s message.

Elmer and Boris Meet for the First Time

Elmer is emotionally lost after his mother’s rural store goes out of business and they move into the city, where they struggle to pay the bills and begin to fight, which they had never done before. He decides to travel to Wild Island to capture a dragon that he will bring back to the city and charge people to see. Elmer has certain expectations for what Boris will look like — large, muscular, strong — and when he meets the blue-and-yellow-striped, goofy dragon, he’s forced to reconsider his plans.

Meg LeFauve: We wanted the boy to have an expectation of what dragon he was going for. If you said to him, “Well, this one doesn’t fly, and he’s kind of goofy,” it would be like, “Why is he getting on the whale to go to Wild Island in the first place?” To drive him there, this dragon has to be his solution to his problem, and he needs that dragon to be strong and fierce and fly and breathe fire. You really need to be in Elmer’s emotional point of view and share his expectations. If you’re not, I don’t think that final reveal works as well.

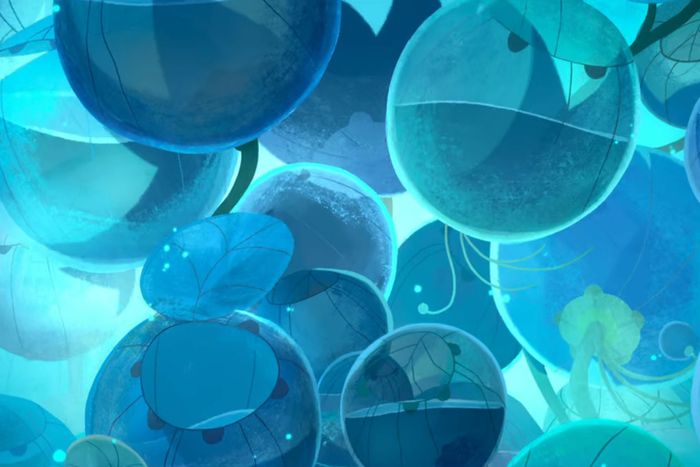

Nora Twomey: We do catch glimpses of the dragon. We know that he’s in that summit enclosure. We can hear him, we can hear his voice bouncing around when he’s behind those big bubble-type shapes. But we did not want to be manipulative, where you’d feel the hand of the filmmaker going, “Oh, we want you to think this, but actually, it’s that!” We wanted you to feel this from Elmer’s perspective. What would he see? What would he think?

We also placed importance on the imagination of children. I read the book to my two boys, and then asked them to draw from the book, and so did our art director and our production designer and a number of people involved with the film at that point. They did things that were just unpredictable. The tiger was a scary kind of character, so they would draw the head really big and the mouth really big in comparison to the body. I was saying to Rosa Ballester Cabo, our production designer, “The ground doesn’t need to be brown, the grass doesn’t need to be green, the tree doesn’t need to look like a tree,” and Rosa drew a big broccoli tree. We felt like we were getting down on the floor and behaving as children, and remembering not to take our imaginations for granted.

I also kind of experimented on my children. [Laughs.] I got my kids and a bunch of my kids’ friends to take a walk through the forest, and I was sneaking along behind them, just listening to their conversation. They were talking about something mundane that happened in school, but as they were doing that, one of them just picked this huge log — this massive branch of a tree — and started dragging it along for no reason. But nobody said, as I would’ve as an adult, “Why are you dragging a log along the footpath? You’re going to trip everyone.” I said nothing, and they all helped to carry this log. Then somebody said, “Watch out for that black hole over there!” So they all maneuvered with the log around this imaginary black hole. That’s unquestioning imagination. It really humbled me, honestly, and as a visual storyteller, it made me want to stop trying to put adults’ rules on how things can and can’t go, and really try to just use my imagination and my heart.

The Aratuah Reveal

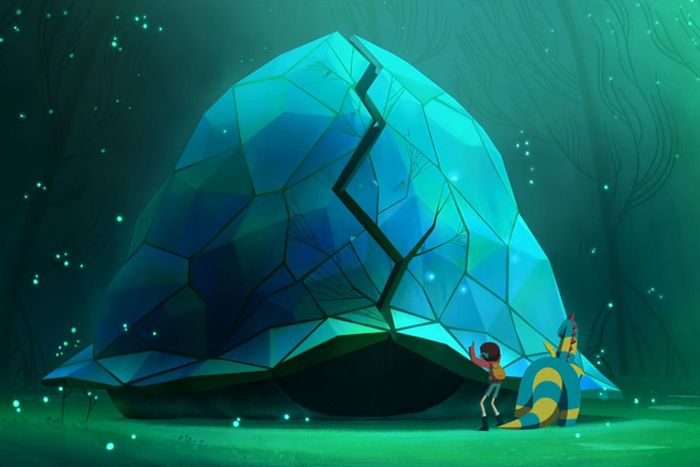

Elmer and Boris travel around Wild Island to try and find the ancient tortoise Aratuah, who they believe will tell them how Boris can save the island and transform into the more mature dragon he’s supposed to become. But when they find Aratuah’s shell, Elmer realizes he’s died — information he keeps from Boris in a cascading series of lies that almost breaks apart their friendship.

ML: The point of the film is that there isn’t an easy next step, there isn’t always going to be a wise mentor to walk up and explain to you the magic key. That can be shocking. And yet for Elmer, he has to let it be.

NT: I think it’s also a lovely build on how when he comes back at the end to his mother, that’s not the same relationship. They hug. It feels wonderful. But that’s not the same Elmer that left for Wild Island. In the storyboard phase, we were looking at ways to bring in humor. They’re just kids, so they’ll laugh at silly stuff at the same time that they’re trying to handle something really, really tough.

From a visual perspective, we built it like a cathedral. Even down to the score: You’ll notice that there’s a cathedral-esque and religious sense to the score and how the echoes in the sound design work. Elmer and Boris feel like two giggly kids in a cathedral, where they’re not supposed to be giggling in there. There’s a seriousness in that moment as well, like a Catholic confirmation or something. Somebody makes some weird noise and you can’t help but giggle. Those very child-like moments started in the script and then we dug into it with all of the visual elements and the voice performances, to try and make that moment feel kind of familiar.

ML: I think everyone in the audience, especially the adults, are expecting that turtle to come out. They’re already projecting what the scene is going to be. When you say, “nope,” that is the shock that the child has experienced. I don’t think it’s just a movie for children. I think all of us as adults have those shocks, and what do you do then? Plus, the score is spectacular. The Danna brothers — I knew them a little bit from their Pixar work, but oh my gosh.

NT: They dig into the same questions that you asked, Meg. They’re not asking, “What tempo should we do this?” They’re asking, “What is Elmer feeling at this particular moment? How is this sequence evolving his journey? What are the notes underneath here, in terms of the themes?”

ML: You told me something about them that I think is so cool, about the levels of sounds?

NT: We had an amazing casting director, Amy Lippens, who had been watching Gaten Matarazzo and Jacob Tremblay and knew that they would be a good match for each other, in terms of the musicality of the film, even the way that their two voices worked together. Jacob and Gaten are two boys that enjoy each other’s company and have the same sense of humor, and yet they’re both young professionals. Gaten had little control over his voice at that stage. He was just 17, but his voice would just shoot up an octave without him having full control over it in the voice-recording sessions, and he would apologize and then do the line again. But the sound recorders knew, and could see the look on my face, that those were the ones I wanted. That’s the good stuff.

The laugh in Aratuah’s cave really goes up there in terms of pitch, and then that gets echoed around the room by the sound designers. And so when Mychael and Jeff [Danna] were composing their score, they decided to use the lowest noise that the human voice is capable of making, and then this beautiful voice that hits these high A notes. The belly of the island as it sinks right down and the soaring of the dragon and the potential of this friendship soaring above it all — those are all ideas running along that big, strong backbone of the film.

ML: That was the range musically that they used, the boys’ voices. That is so cool.

Boris’s (Non) Transformation

In the film’s finale, Elmer and Boris have a fight that nearly ruins their friendship — Elmer wants to leave the island, while Boris is compelled to try one last time to save it. The two reconcile when Elmer admits he was wrong to underestimate his friend and that he too feels fear, which reassures and encourages Boris to fly into the island’s lightning-filled center and use his magical abilities to destroy the roots sinking the island. When Boris emerges, he looks the same externally, but has transformed by finding confidence in himself.

ML: Boris feels the pressure of Elmer’s expectations for a dragon. In earlier drafts of the script, Boris talked a lot about his family, and how his brothers had become that kind of dragon. He doesn’t know how to save the island — his dad told him, but he forgot, he was really busy thinking about something else. [Laughs.] And so he’s shoving all of his agency over to Elmer. He says in that quiet moment up on the mountain, “I would have just failed anyways.” So it’s very important for that character to claim himself. His power is in being that roly-poly, silly dragon, and he doesn’t have to change it, he has to embrace it. We knew he wouldn’t physically transform.

Elmer’s arc is that he has to let this dragon do something uncontrollable. He’s on this journey because of the loss of his mother. Now he’s gotten a new intimate, emotional, vulnerable relationship, and that person is saying, “I’m gonna go.” I remember talking to Nora and saying, “The only thing I desperately care about visually is that, after the island is all beautiful, there’s a moment where Boris isn’t coming up.” It’s like, “Oh my God, this was a real sacrifice, potentially” — and when he comes back, “Yay!”

NT: There’s something very strong about Boris not getting the six-pack. Your transformation is never the transformation that you think it’s going to be. The fear is still there for Elmer and Boris, they just have grown a bit bigger than it: “Are you scared?” “Yes, I’m scared too.” There’s a humanity and a vulnerability being brought into storytelling, where maybe the protagonist doesn’t get everything that they want. Maybe the answer is generosity over external strength. Searching for that kind of truth makes me really happy.

Members of the audience, be they four years old or 84 years old, we’re all coming of age all the time. And all we have is each other. As a storyteller, I feel like my role is to be a companion for those kind of journeys. If I fail, I do it happily; if I succeed, that’s great. But at least there’s an honest attempt to try and give some kind of meaning to the chaos. There is something about animation, and whether it’s 3D, stop-motion, or hand-drawn, it doesn’t matter. It’s the distilling of human experience through the eyes and hands of artists, and it invites audiences in a way no other medium can. It lets you into a specific space of human empathy. It’s a very exciting time for animation, and I think we’re only just scratching the surface of what it’s capable of.

This interview was conducted at the 2022 Virginia Film Festival and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Related

- The Bluey Method of Reducing Grown-ups to Tears

- Makoto Shinkai’s Weepiest, Wettest, Most Intricately Animated Movies

- The Best Berserk Adaptation Is Finally Available Again