There were small clubs in London in the early 1960s that, on a typical evening, were packed with riffraff, mostly unwashed boys from nondescript backgrounds, art-school dropouts at best. Surely there were nights when a certain group all happened to be present at the same time. Back then, few besides their immediate friends and family would have recognized them. Today, they’re household names. Mick Jagger, Keith Richard, and Brian Jones; Mick Fleetwood and John McVie; Peter Townshend and Roger Daltrey; Ray Davies and his brother Dave.

Among them was a guitarist, Jeff Beck, whose eventual celebrity (and, no doubt, bank account) would always be a bit smaller than the others’. His aloof mien masked a strain of volatility, and perennial musical dissatisfaction made working with him, by many accounts, difficult. But his guitar skills were a match of any of his peers, and he would go on to record for nearly 60 years, displaying again and again a mastery of the instrument’s sonic possibilities that was among the most adventuresome and advanced of his generation.

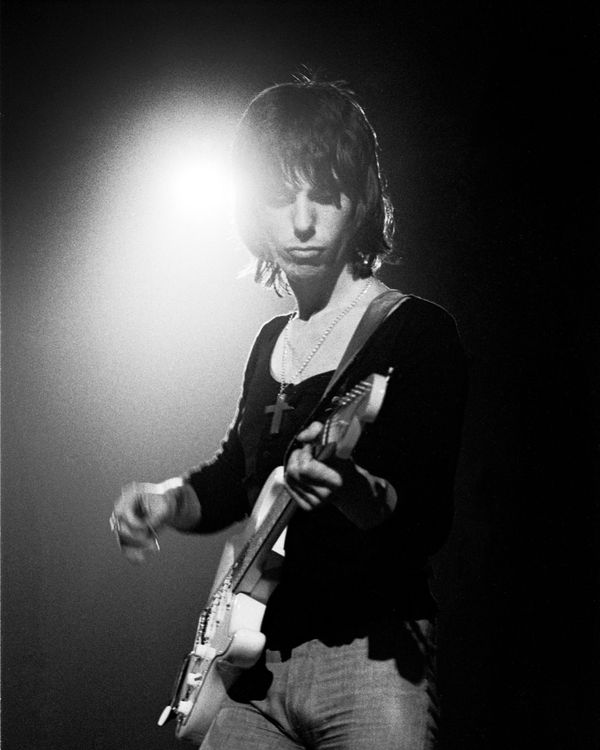

Beck, whose death at 78 of bacterial meningitis was announced by his publicist this week, became best known for playing in the Yardbirds during its most successful incarnation. He soon left the band to form the Jeff Beck Group, with Rod Stewart as lead vocalist, and then a tough power trio, Beck, Bogert & Appice. In both, he was the very incarnation of the British rock star, lean and focused, with an enviable pile of hair. (“He had that weird pineapple cut that a few English bands had,” drummer Carmine Appice would later recall.) After that came a 50-year career of increasingly adventuresome solo work, ranging from fusion to techno, hard rock to rockabilly to the Great American Songbook — even a cover of “Nessun Dorma.”

Beck’s playing stood apart; he was among the wildest of players, yet also the most controlled and precise. He unquestionably had the widest range of influences of any of his peers; never doctrinaire about the blues or anything else, he could play in any style. He was a student of guitar effects and unleashed essays of unearthly sounds, but always with a mind-bending clarity and precision. He was, for a time, the leader of the band that some thought might claim a heavy-metal crown from Led Zeppelin, but was just as comfortable displaying easy-listening jazz chops on songs by Charles Mingus or Narada Michael Walden. And in an industry of showoffs and sociopaths, he was a showboat only onstage, tending to be aloof elsewhere, one who kept his own counsel on just about everything but the music.

Beck had grown up in Wallington, a suburb about ten miles south of London; he was infatuated with the guitar, and as a youngster had met someone quite like him, Jimmy Page. A few years later, Beck ended up playing in a band called the Tridents; by that time, Page was a prodigy on the London recording scene working prolifically, and remuneratively, as a studio musician — and pushing Beck into the business as well.

He eventually joined the Yardbirds. The band is pretty much forgotten today, but they remain of interest to rock fans for having produced an impressive spring of guitarists — first Clapton, then Beck, and then Page. The original Yardbirds had a serious front man in Keith Relf. Like the Stones, they began as sober and serious devotees of American blues music, and had a reputation based around their live blues “rave-up,” where they would embark in high-energy instrumental breaks, driving their club audiences into a frenzy.

But the bands were fighting a rearguard action. In their minds they were honoring the music, but all around them, the managers and record labels that controlled their careers smelled the money that could be made in the wake of the emergence of the Beatles. One by one, the doctrinaire defenses fell. Clapton was a blues diehard. He didn’t like a pop single the band had recorded, so he left. The Yardbirds, looking to replace Clapton, turned to Page. He passed and referred them to Beck. Recalled Relf:

“Our manager … told us to audition Jeff. We did, and wow! What a wreck he looked. His hair hung matted below his shoulders, his jeans were torn open. [We] muttered, ‘Oh, no!’ And then he started to play, and it was like a healthy chunk of heaven dropped into our lap.”

Beck joined just as “For Your Love” — the single Clapton didn’t like — began its race up the British charts to number one, and into the top ten in the U.S. The Yardbirds recorded their next single with Beck. “Heart Full of Soul” became another solid hit, with Beck delivering a fuzzed-out guitar riff that, along with the Kinks’ earlier “You Really Got Me” and, a short time later, the Stones’ “Satisfaction,” would limn the new frontiers in electronic sound.

The band in its own way widened the sound of the music, working with unusual instruments and slotting in unexpected instrumental breaks. Beck was the driver behind their incendiary cover of “Train Kept a Rollin’,” and delivered a blistering performance in “You’re a Better Man Than I.” But their history is also a reminder that the groups that came together and survived in that era were charmed. Others, like the Yardbirds, weren’t so lucky.

Everyone in the band was unhappy. Beck bought bigger and bigger amplifiers, drowning out Relf onstage. Refl quickly fell victim to alcoholism and insecurity. Beck grew more surly and began destroying equipment at the end of shows. “He got his emotions out through his guitar and extreme amounts of semi-violence,” Yardbird Chris Deja would recall to biographer Trevor Jones. “He became very, very moody. He became unpredictable. And in fact, at times, it was quite unpleasant because it wasn’t part of the performance. … And that was embarrassing and stressful for everybody else.”

Bassist Paul Samwell-Smith eventually quit; Page, bored with session work, took his place as bass player, and then quickly moved to guitar. Suddenly the Yardbirds had two of the best guitarists in rock fronting their act. But the two friends never jelled, and Beck would eventually split. He had ambitions to build his own bespoke group, one that would meld the blues, pop, Motown, and the emerging heavy metal. He was waylaid by the machinations of producer Mickie Most, who essentially forced Beck to record a single called “Hi Ho Silver Lining.” Americans have never heard the song, but it became a minor hit in England and then, unaccountably, a beloved schlock-pop favorite in the U.K. for decades. Stewart would later write that Beck considered the song a “big pink toilet seat” hanging around his head for the rest of his career.

By 1967, he had put together the Jeff Beck Group, with Stewart and Ron Wood. While they wowed parts of the U.S. on a tour, Beck’s perfectionism, churlishness, and dissatisfaction meant that they would never hit the heights the talents of its members suggested it might. The period was all the more difficult for Beck because his pal Page was then launching Zeppelin. “Jeff retains a grudge, I think, because they took the nucleus of what we had and made it more commercial,” Stewart reflected. “The Jeff Beck Group could in due course have been Led Zeppelin, frankly, except for the crucial detail that they were a step ahead of us in coming up with original material.”

Plans for a supergroup with drummer Appice and bassist Tim Bogert fell apart when Beck was injured in a car accident. The trio recorded an album a few years later, and went on tour, but this alliance, too, went to ground when the other two players found Beck mercurial and untrustworthy. After that, Beck embarked on a wild, and sometimes quizzical, solo career. His early solo records, Blow by Blow and Wired, showcased the wide variety of his approaches, from blistering fusion to groovy, easy-listening jazz workouts. (Both albums eventually went platinum.) He then went full fusion with Jan Hammer, the Czech keyboardist who had come out of the high-fusion Mahavishnu Orchestra with John McLaughlin.

At that point Beck was a highly respected player capable of making an occasional mark with compositions of his own, like the concert favorite “Beck’s Bolero,” and flaying and sometimes filetting standards of all manner of sorts, from “Jailhouse Rock” to “Ol Man River,” from Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition” to the Beatles’ “She’s a Woman.”

He’s also known for a wide variety of session appearances. That’s Beck delivering a scorching solo in the middle of Jon Bon Jovi’s otherwise highly silly “Blaze of Glory.” He could also guest comfortably on albums by Walden or Stanley Clark. You can hear him delivering less-than-stellar work on the long version of Tina Turner’s “Private Dancer,” too. And here’s a pretty amazing meeting of Beck and John McLaughlin, doing a take on the song “Django,” which Beck had sat in on in the studio version.

Beck’s personality, so many years on, remained somewhat opaque. Few of the memoirs of the time leave a good impression of him. Beck’s relationship with Clapton seems to have been a bit distant. In Clapton’s autobiography, Clapton allowed he “rated” (i.e., appreciated) Beck’s talents, but then notes that he, Clapton, had been steeped in the blues, where Beck came more from rockabilly — and barely mentions Beck otherwise. In another interview, Clapton dismissed Beck as “adaptable” — a pointed word for someone who’d left the Yardbirds on principle.

Rod Stewart emanates ambivalence about Beck as well. He insisted he did not, as was apparently reported, hate Beck, but allows that Beck was volatile, and went through backing musicians at an “alarming rate.” While always praising Beck’s talents, he spends a great deal of time in his autobiography describing in sometimes sharp detail the ways in which Beck was not cut out to be a bandleader. (Beck was perfectly capable, Stewart says, of hopping into a limo and leaving Stewart and Wood to find their own taxi.) With a straight face, Stewart talks at some length about whether Beck was or was not the model for Nigel Tufnel in This Is Spinal Tap.

Indeed, in Carmine Appice’s sex ’n’ drugs ’n’ rock-and-roll-drenched memoir, which gives a complete history of the rise and fall of the Beck, Bogert, and Appice power trio, the drummer relates how Stewart advised him not to get involved with Beck, and later saw the wisdom in that advice. He says Beck dropped out of the middle of a tour with no notice, leaving the rest of the band and its road crew in the lurch — and that Bogert eventually slugged Beck. (In fairness to Beck, it does seem that Bogert and Appice, both pranksters, seemed to spend a lot of time trying to catch Beck in flagrante delicto with female fans.) The drummer also says that he worked for months with Beck on a Beck-Appice project, only to be dumped and have his songs repurposed for the Blow by Blow album, with no credit.

As the years went on, the culture folded in on itself, and even an austere presence like Beck’s could not avoid it. A few years ago, he stood in a receiving line with Clapton, Page, and Queen’s Brian May to meet Queen Elizabeth II. His last recording release, ironically, was a collaboration with Johnny Depp, 18, mostly odd covers, which came out in 2022. He continued to play live, baring his recombinant style — psychedelia, fusion, blues — in front of an intense small backing combo. Behind him, often, was bassist Tal Winkenfeld, whose calm lines prowled musically behind Beck’s wild excursions. In these later years, in clubs and as a stalwart presence in the big all-star rock gatherings, Beck could still wow a crowd with his thunderous instrumental take on the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life,” and present a striking figure; clad in a sleeveless shirt, his bare, taut arms and still-bushy classic British rock star shag giving him a palpable sexuality onstage into his 70s. He remained the “guitar hero’s guitar hero,” as Guitar World called him, to succeeding generations of players. Vernon Reid, after tweeting “FUCKING NO!” when he heard the news, later wrote, “The greatest thing about Jeff Beck is that he was NOT hung up on how GREAT he was. In this way there was always space for him to grow. About the size of a garage.”