In my new book, Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, I try to write the autobiography of the audience. I don’t want simply to list a catalogue of people who said or did something rotten; instead I’m exploring the way the knowledge of an artist’s real-life biography disrupts the audience’s experience of the art. A monster, in my mind, was an artist who could not be separated from some aspect of their life. J. K. Rowling—who has only become more blatant in her anti-trans statements since the writing of the book—is one such artist.

An excerpt from 'Monsters: A Fan's Dilemma'

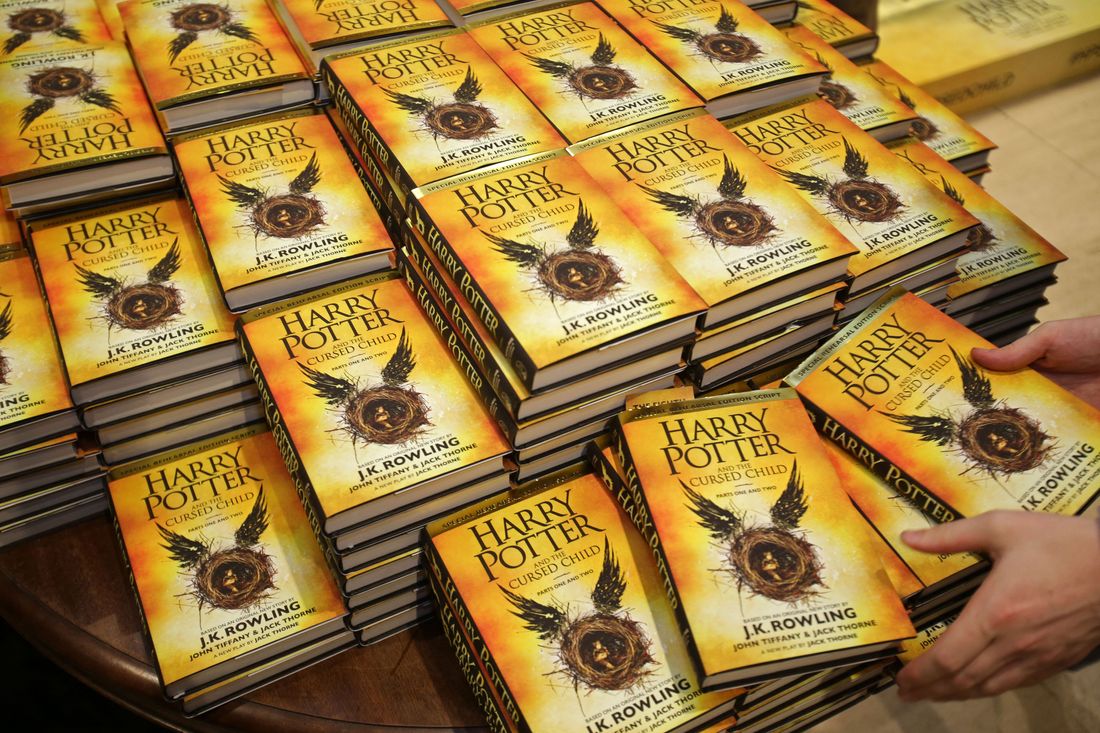

In the first two decades of this century, the Harry Potter books took over children’s imaginations. That’s an easy way of saying something more poetic, more difficult, stranger. Children who came of age in the aughts and the teens (and even now) had their imaginations, their dreams, their very sense of themselves invaded by Harry Potter.

I was the parent of one such child. I accompanied my child to midnight drops of new HP titles. I attended Harry Potter conventions. (Hard to imagine a more delightful sight than the bland corporate halls of the Oregon Convention Center filled with shrieking eleven-year-olds swooping around in cloaks.) My kid barreled through each book as it was released, then read and reread until it became a part of her. I read more slowly, and even more slowly still I read each book out loud to the youngest child in our family. So I read Book One at the same time that I was reading, say, Book Five, and could see how Rowling had seeded elements of the later books’ plots right from the beginning. The reader is left with a sensation of an ordained universe, a place where things make sense if you just pay attention. It’s easy to see how appealing this could be for young readers—especially for YA readers, people who might be starting to feel that the world doesn’t make sense at all. Also addictive were the books’ two systems for ordering people. First you divide the muggles from the wizards, then you divide the wizards into houses. Everyone is chosen. Everyone has a special identity. It speaks to the same drive that makes adults take Myers-Briggs tests, an endless fascination with the parameters of one’s own selfhood—and that fascination is rewarded with the fantastical idea of belonging to an imagined tribe of people (or wizards) who also hew to those same parameters. In other words, the books offered a navigable system for belonging—alluring, perhaps especially, for a person who didn’t entirely feel like she belonged in the real world. Which describes a lot of preteens, and especially a lot of preteens with a dawning sense of their own queerness. Harry Potter fan-ship twined with the growth of the Tumblr platform, which in turn twined with the growth of a new kind of LGBTQ+ movement … kids who found solace in un-embodied community, whether it was Hogwarts or online. It wasn’t quite telepathy, but it was the dream of telepathy.

Reading has always been a one-way communion, but the kids in question solved that by talking back—to each other. They wrote endless fan fiction, reams and reams of it. They created their own art in response to Rowling’s work. They gave birth to a Potter-centric DIY movement where they were in artistic conversation with the books: I took my kids to Harry and the Potters shows—the band that founded “wizard rock” or “wrock”—and to live performances by Potter Puppet Pals, an online parodic series spinning off from the books.

This was all done with silliness but also great seriousness. I remember one particular performance by Harry and the Potters, an actually really great band led by two brothers who mostly sang their (very funny, very catchy, somewhat punk) songs from the point of view of Harry himself.

On an August afternoon I stood in the back of a small, hot, airless box of a venue in Olympia, Washington, filled with hipster parents and their kids. The kids in the audience were wild with happiness, singing along to every song, vowing to fight Voldemort’s agents of darkness, joyfully overheated in their capes and their long Hogwarts scarves.

I happened to lock eyes with the singer at one point. I gave him an indulgent, conspiratorial smile, as if to say, Aren’t these kids and their Harry Potter obsession adorable? He stared back at me stonily—his look said he was utterly committed to the collective fantasy the room was having. There was nothing adorable about it—it was serious stuff. Something useful and real and powerful was happening there—something that was helping these kids. (One of the brothers went on to join the queer communist hardcore band Downtown Boys, which makes perfect sense on further reflection—Harry Potter culture was, in many ways, about stickin’ it to the man.)

The notion of belonging to a club—the notion of having been sorted—tied these children and young people together in shining bonds of connection. They reached each other box to glowing box throughout the night. This is a common story for us all, of course. We’re doing our best to practice telepathy, living up to the legacy of Alexander Graham Bell. But for these kids—especially these queer kids—the Harry Potter fandom was an intensified kind of identification, and it took place in an imagined world whose geography was as real as—realer than—that of the world where they lived.

In 2020, J. K. Rowling began to signal that she was aligned with the growing “gender identity” movement in England. Rowling argued that gender was determined by sexual organs, and moreover that denying this truth endangered the lives of girls and women. Rowling wrote a statement on her website worrying about “ ‘inclusive’ language that calls female people ‘menstruators’ and ‘people with vulvas.’ ” She argued: “I want trans women to be safe. At the same time, I do not want to make natal girls and women less safe. When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he’s a woman—and, as I’ve said, gender confirmation certificates may now be granted without any need for surgery or hormones—then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside.”

The backlash across the internet was a great fury. Many of the former Potter kids were trans and they were rightly very angry. But underneath the fury was a deep sadness; the sadness of the staining of something beloved. Rowling’s tale of a place where otherness was accepted didn’t in the end include them. If you are a trans person, or love a trans person, or simply disagree with Rowling’s language, what then to do with that part of your childhood that had become intertwined with Harry Potter? Children had been part of a mass marketing phenomenon—after all, were the HP books really any better than, say, the witchy novels of Eva Ibbotson? These kids were scooped up in a dream that had been rocket-fueled by the internet and by the coalescing power of capitalism. The good news was that it was a dream of love—that was what the Harry Potter books were ultimately about: a dream of a place where outsiders were accepted and where love triumphed over evil.

Some of these children grew up to be adults whose dreamscape was taken away from them. Did they lose an imagined landscape where great swathes of their childhoods had been spent? I’m picturing a hillside, strip-mined.

I wondered, too, about shame. The threat of being shamed lurks at the edges of all of internet life. What role does shame play in this dynamic between fan and fallen artist? Shame is noun and verb; it’s something I can feel inside myself, but it’s also something I can do to you. When we love an artist, and we identify with them, do we feel shame on their behalf when they become stained? Or do we shame them more brutally, cast them out more finally, because we want to sever the identification? Maybe shame is the ultimate expression of the parasocial relationship. Our emotions, collapsed together with those of the artists we love, leave us vulnerable in ways that are entirely new in the internet era. No wonder we don’t know how to behave in this new landscape, or even how to feel.

Excerpted from Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, by Claire Dederer Copyright © 2023 by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Reprinted by permission of Knopf.