Lee la noticia en español aquí.

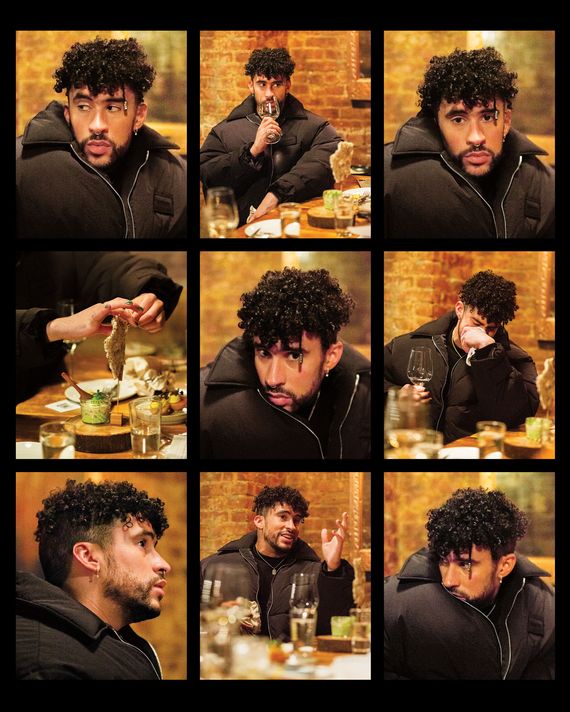

Estamos activa’os!” Bad Bunny tells me when I meet him and his three-person crew at a Michelin-starred restaurant in the East Village on one of the first cold nights in November. He’s buried in a big black puffy coat, scrolling through his phone; a single curl is braided and looped through a little plastic bead that hangs over his left eye. The only noticeable remnant of Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio’s larger-than-life alter ego is his nails, which are decked out in an immaculate green manicure.

There’s a brief silence and some stifled laughter around the table. It’s painfully obvious that the energy levels at the moment are extremely low — decidedly not activa’o. Martínez Ocasio looks like a bored, tired kid dragged to a family function. “Well, we’ll get there,” he assures me, taking a sip of white wine.

In person, Martínez Ocasio exudes a humbleness that belies his star power. Perhaps it’s how frequently he mentions his mother, both in conversation and in songs. “When she listened to ‘Safaera,’ ” he says — referring to the song off YHLQMDLG that pays homage to early reggaeton (back then, we called it “underground”) in its sexually explicit lyrics — “she sort of scolded me.” He puts on a gentle but concerned voice and begins imitating his mother. “Benito, te safaste,” he recalls her saying. “My God, you went over the line!” Or perhaps it’s that he’s still running with the same crew he has had since he was growing up. (His high-school friend Pino is joining us for dinner.) Not to mention that when two Puerto Ricans meet anywhere outside of the island, they’re never quite strangers. I am frequently reminded of hanging with my cousins back home when Martínez Ocasio makes funny little sounds as our plates are delivered to the table. “Some little snacks for you,” announces the server, to which he responds with a “Brr!” “Here are some crispy deviled eggs” elicits a “Bop!” He declares a fluke tartare to be “bien bellaco,” or “very horny.” Every other sentence is liberally sprinkled with “cabróns,” a catchall cussword that can mean something is very cool, very bad, or very difficult — or that someone is an asshole. For men of a certain age on the island, the word is simply a stand-in for dude.

“It’s been un año cabrón in a lot of ways,” Martínez Ocasio says. After almost two years of canceled shows, he has been flying around the world for detours into acting. He’s in town to promote the third season of Narcos: Mexico, the Netflix series in which he plays El Kitty, a “narco junior” who rolls with the Arellano Félix clan, the family that rules the Tijuana cartel. After filming his episodes in Mexico, he went to L.A. for a part in director David Leitch’s upcoming Bullet Train with Brad Pitt. In February, he was in New York to perform as the musical guest on Saturday Night Live, in which he played a pirate and a dancing plant, respectively, in two sketches. He loved every second of it. “If acting is something I can continue doing in the future, I would love to do more comedy, and maybe drama, rather than the action path I am currently on,” he says. “Action movies are the last kind of movie I want to watch.” (The week before, he binged all the Harry Potter movies for the first time. “Now, everything is a reference to Harry Potter, a joke about Harry Potter. I kept thinking, Why haven’t I seen them before? I’m full of regrets.”) But it’s possible Martínez Ocasio’s most memorable performance this year came as part of another franchise that requires an innate facility for comedy: WWE’s WrestleMania. He moved to Florida for three months this spring to train. As a hard-core fan, he knew the rest of the fandom would be skeptical. “They are not Bad Bunny fans. They do not listen to reggaeton; they listen to metal,” he says. “I know they hate me, and I think it’s funny; I love it. I was so ready for the hate.” In the end, he won them over. It was a remarkable debut. Watching Bad Bunny wrestle in the ring, jumping off the third rope and doing a “satellite headscissor,” was like watching someone live his childhood dream.

Given Martínez Ocasio’s career trajectory over the past five years, it would have made sense for the artist to take the forced time off from touring as a vacation. (He will return this winter, beginning with his huge P FKN R show at the Estadio Hiram Bithorn in San Juan in December.) He began uploading songs to SoundCloud in 2014 when he was working as a bagger at a grocery store in Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, the town where he was born and raised. Two years later, he signed a deal with DJ Luian’s Hear This Music label. He quickly emerged as a unique artist in the Latin trap-urbano genre because of his somewhat flamboyant fashion sense and the fact that he wasn’t afraid to sing about having his heart broken — a marked difference from the macho, sex-driven lyrics so prevalent in the genre (though he had plenty of those as well). He released a string of popular songs, often featuring heavy hitters — Daddy Yankee, Karol G, Farruko, and Anuel AA. By the time he guested on Cardi B’s “I Like It” in 2018, his presence on the track was almost a two-way co-sign: Here was Cardi introducing Bad Bunny to a larger international- audience, and here was Cardi signaling to the Puerto Rican and Latin American communities that she “got it.”

From there, he released four massively successful, critically acclaimed records in quick succession. His debut album, X 100pre, came out on Christmas Eve 2018, and in 2020, he put out another two studio albums plus a compilation of songs he had lying around, Las Que No Iban a Salir. He reads his reviews. “I don’t take them all seriously — the good ones I carry with me,” he says. “The bad ones, sometimes you read them and you think, Damn, they’re right. You realize they aren’t bad reviews, just valid criticism. Then there’s people who are on a crazy trip, and you have to ignore them.”

Martínez Ocasio began work on his fourth studio album this year but is keeping quiet about it. He remains a spontaneous singer-songwriter. “When it’s time to write the songs, I don’t sit down and think” — his voice drops into a comically serious tone — I am going to write this song thinking about that person and everything that happened during that summer of 2001. Afterward, I realize it has something to do with something personal or things that happened to me in the past.”

Part of being internationally famous is the increased scrutiny on everything you do. In October, “Safaera,” one of his most popular songs, sparked a minor controversy when Bad Bunny, along with the artists featured on it, was sued for copyright infringement by AOM Music, Inc., a company that owns the rights to many of the songs by one of the genre’s earliest icons, DJ Playero, that were sampled and/or referenced on the track. In an interesting twist, DJ Playero released a statement claiming he had no knowledge of the lawsuit and that, for a number of years, a company he has no affiliation with has been profiting from his songs. When I bring it up, Martínez Ocasio replies, “We aren’t talking about that.” I mention how much I enjoy the song’s deranged lyrical content, and he perks back up. “What I can tell you about the lawsuit is you get the experience of hearing an American lawyer say” — he switches to an Americanized accent — “ ‘Chocha con bicho / Bicho con nalga’ in a very serious tone.”

The lawsuit came after another public kerfuffle. In September, the Colombian artist J Balvin — who has frequently collaborated with Bad Bunny, including on the 2019 joint EP Oasis — voiced disappointment with the Latin Grammys for not valuing the urbano genre and called for a boycott of the organization (he had received three nominations that year, two for his song “Agua” from The SpongeBob Movie: Sponge on the Run). The Puerto Rican artist René Pérez Joglar, who records as Residente, was offended that Balvin would call to boycott the awards in a year honoring the legendary musician Rubén Blades. He also memorably compared Balvin’s music to a hot-dog cart. Martínez Ocasio waded into the debate during an interview with a Dominican radio program. “If I were a Grammy judge,” he said, “I wouldn’t even nominate ‘Agua’ for the Nickelodeons [i.e., the Kids’ Choice Awards], and they took him into consideration.” I ask if he has spoken to Balvin recently. “About the hot dogs and the whole thing? Nah, not really, but here I am eating a five-star meal,” he responds, sending the table into fits of laughter. “I haven’t talked about it with him, but I also don’t think it’s necessary. What I said in that interview was my normal opinion. He knows I respect him, his music, and what he does. People think him and I are friends, like we talk every day. We don’t have the type of relationship where we talk all the time and hang out, you know? I don’t really have that kind of relationship with other artists. I find it very hard.”

It’s not surprising to learn that Martínez Ocasio has mostly retired from social media, though he does resurface on Twitter every once in a while with something cryptic and sort of poetic, like “I’m in pain but I don’t know where” and “Sometimes you think yes, but no,” or on Instagram, where he posts sporadic selfies. (Last year, hundreds of thousands of people tuned in to watch him play snippets of new music on a three-hour Instagram Live.) I ask if he has a secret Instagram account. “Ayyyy!” he replies, laughing. “What’s going on?” (He acknowledges a Bad Bunny finsta does exist.) “I post less and less every time,” he says before launching into a vaguely boomer-esque rant about social media. “I used to be on my phone all the time, but in the last year or so, I’ve learned it’s just not necessary. I mean, papi, if you are talking to your girlfriend, that’s cool; if you are talking with your friend, that’s cool; if you are talking with your mother, that’s supercool. But canto de cabrón, if what you are doing is scrolling Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, you are stupid, you understand me? Like, truly, I would rather you just leave. Because here we all are having fun, we are talking, we are joking, we are telling stories, anecdotes, talking about our experiences, and you are on fucking Twitter or fucking Facebook.”

“And, listen, I get it,” he continues. “People do that without even thinking. If I were to shut up right now, if I stopped talking, you would grab your phone and start scrolling. But it’s like, cabrón! We can just sit here in silence. We can enjoy the silence. Silence is not synonymous with boredom.”

I wonder how much his fame has to do with this desire for everyone to live in the moment along with him. How much of it is a fear that someone may be breaking the circle of trust inherent in a friend group when there’s a celebrity at the center. In the past three years, his star has kept rising exponentially: He broke beyond the Latin American music market and into mainstream American culture; he has appeared on TV shows and in movies and made a record and a record and another record. In Puerto Rico, we have a saying: “No es lo mismo llamar al diablo, que verlo venir” — it’s not the same to call the devil as to see him coming, or it’s not the same to think about something as to actually deal with it. You grow up, you want to become famous, but what happens when you do?

I ask him when he first realized he was famous. He takes a few seconds to think. “I realize every day, I swear,” he says. “Two or three weeks ago, I was talking to myself, trying to get myself to accept it, like, Cabrón, this is who you are now. You have to learn how to live with that.” He seems a bit tortured about it at the moment. “I’ve been crashing against this,” he says. “When I go out and someone asks me for a photo — there’s nothing wrong with that! But there’s also nothing wrong with that making me feel bad.”

“Maybe I like attention,” he continues, “but it’s Benito who likes attention. He likes to joke with his crew. But once I am in a group of strangers, I am shy and quiet and reserved until I feel a little comfortable.” I’m caught off guard the first time he speaks about himself in the third person. But it strikes me as a tool he uses to continue being Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio from Vega Baja, who had already declared himself to be living “like he always dreamed about when he was 17,” as he sang on “Estamos Bien” in 2018, when he was not yet an international household name.

Toward the end of our meal, Pino, the high-school friend, shares that he will turn 27 the next day; Martínez Ocasio turned 27 earlier this year. I ask if they know about the return of Saturn. The singer leans forward seriously: “Tell me about that shit.” I explain how the planets align in a person’s 27th year, how it’s a time for assessing one’s life, for thinking about change, for introspection.

“I didn’t know about that,” Martínez Ocasio says. “That fills me with peace, knowing that’s a thing. The past year has been shit. De pinga. Really.”

I tell him the shit is part of it too. “You’re right, that’s part of it,” he says. Still, it doesn’t make it any easier, he insists. “I am going through it right now. I am telling myself I’ve been dealing with this for a while; I need to accept it. I am still suffering through so many things, and I know that everything that’s happened is part of life, and it has to happen. I learn from it, I cry about it, and I move on.”