Alice Neel was the painter par excellence of New York’s human comedy. She rendered friends, sons, lovers, strangers, addicts, activists, self-anointed shamans, cultural kings and queens, the magical, the lost, and the damned in keyed-up harmonies of color. She often outlined people in an electric blue that made each individual vibrate like an archetype. Neel’s eye penetrated her subjects: We see their lives, creative beauty, personal grace, wounded delusion. We see how they have been butchered by life. Her gaze is loving but predatory; she appears to feel with her subjects but never fully for them. This connects to her contemporary Andy Warhol — although instead of Warhol’s candy-colored portraits of the rich and famous, Neel mostly made portraits of our fellow beaten ships of the human soul. Their visages hit us like depth charges. I love her work.

In March, the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its magnificent survey “Alice Neel: People Come First,” which features more than 100 paintings, drawings, and watercolors made between the 1920s and Neel’s death in 1984. At this point, Neel has become a beatified artist, almost a fridge-magnet artist like Frida Kahlo. In 2017, the New York Times dubbed Neel “one of America’s most inventive and peculiar portraitists.” (I’d delete “peculiar” and add “epic.”) The Met show is as close as we’re going to get to a must-see blockbuster in our socially distanced, timed-admission COVID moment.

Neel’s story is one not only of great talent but of artistic courage, persistence, and will. Born in Merion Square, Pennsylvania, in 1900, Neel attended what was then called the Philadelphia School of Design for Women; reportedly, she did not want to be distracted by boys. Over the course of her life, Neel took and shed lovers, became a communist and ardent civil-rights supporter, was on and off the Works Project Administration, supported and was supported by men, had a nervous breakdown, lived downtown and uptown, was in mixed-race relationships, lost one child before having three more, and never stopped painting. This even though she barely sold a thing and received little recognition until the late 1960s. At the time of her death, she had about 300 unsold paintings in her apartment.

There is a mournful chord and an existential shiver in all of her art — life hanging by a filament, mixed with the will to survive. Neel had some of Whitman’s dispassionately passionate gaze. She seemed to emulsify things, then merge with them. Sitting for Neel’s portraits must have been exhausting: Her subjects recall her continuous patter, tales of her sex life, and being lulled into submission, some removing more and more clothing until they ended up naked. Neel said that her identification with her subjects was so “intensified when I paint them, when they go home I feel frightful. I have no self — I have gone into this other person.”

Neel’s early adulthood was harrowing. In 1924, she met and fell in love with the Cuban painter Carlos Enríquez, the son of a prominent Havana family, and they married the following year. Shortly after, Enríquez returned to Cuba, and Neel eventually joined him, with some hesitation; she knew that if she went with him, she’d have to play the role of wife. In Havana, they painted together, mingled with other artists, and Neel gave birth to a daughter. The little family moved back to the United States, settling in the Bronx. Then disaster struck: In 1927, their baby died of diphtheria. Neel was shattered. “I was frantic … I was already in a trap. All I could do was get pregnant again,” she later told biographer Patricia Hills, and she soon did.

Less than a year after the loss of her first child, Neel gave birth to another daughter, Isabetta. Well Baby Clinic, one of Neel’s paintings from this time, depicts the horror of a local maternity ward with screaming babies, maniacal mothers beseeching a smiling doctor for pills. In painting, Neel is pictured standing in the corner, stunned by the scene, just holding her little baby and looking like a lost Madonna. It’s something out of Dante. During the day, Neel left the child with Enríquez and went to paint in the Village. He grew antsy. Then calamity struck again: Enríquez left her and took their baby to Cuba. Neel was suddenly alone in New York. “I loved Isabetta,” she said, “but I wanted to paint … at first all I did was paint, day and night” Then she learned that Enríquez had left Isabetta in Cuba and gone to Paris (Neel would only see her daughter a handful of times again in her life).

“That was just the end of everything,” Neel said. “I was abandoned.” In 1930, Neel had a nervous breakdown. She attempted suicide by gas, was placed in a mental institution, and tried to eat shattered glass. Around that time she wrote, “Now is the great renunciation … I have no strength, my mind is weak and tired and my body sluggish … I’ve lost my child my love my life.”

But she survived, and after getting out of the sanatorium, Neel moved to the West Village. There, she mingled with artists, painted, and took lovers. “I had to reach my sexual aim,” she later said. In 1934, one lover, a merchant marine, burned around 200 of Neel’s drawings and destroyed more than 60 of her paintings in a jealous rage. (In time, Neel saw him again, as she did other lovers after formally breaking up with them.) All this time, she was getting by on — then being let go by — the WPA, as government funding for artists came and went. In 1938, she met José Santiago Negrón, a Puerto Rican musician, at a nightclub and eventually asked him to come home with her. Negrón was married to someone else, but he went anyway; the two had a son together in 1939. Two years later, after she and Negrón had split up, she had another son by a different man. She raised both children as a single working mother, painting all the while.

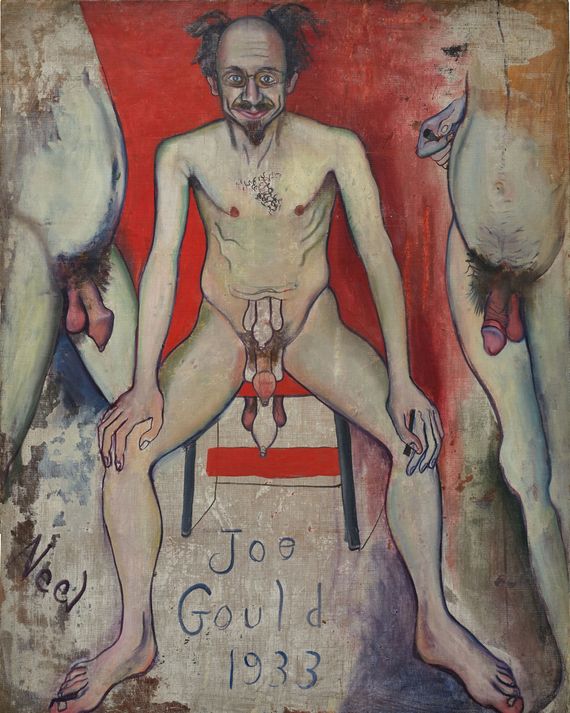

A great show could be mounted of all of Neel’s many subjects: her interiors, still lifes, landscapes, cityscapes, and symbolist works. (Her 1932 painting Symbols (Doll and Apple), which shows a rag doll on a table with a pictograph for the sun and a cross, ranks as one of the great memento mori of the 20th century.) But the primary subject of the Met show is Neel’s portraiture. The work is installed non-chronologically by themes like Home, the Human Comedy, New York City, Motherhood, and the Nude. In this last category, don’t miss the rascally Joe Gould from 1933, a portrait of this emaciated Greenwich Village character with a Lenin goatee and leering eyes, seated naked on a stool with his knees spread, displaying three onion-headed uncircumcised penises and three bulbous scrotums. On his left and right are attendant figures with bulbous male genitalia. (Gould himself loved the painting: “I have a hunch that one of these days, the way people are growing accustomed to the so-called obscene, it will hang in the Whitney or the Metropolitan,” he wrote in a letter to a friend in 1946.)

In smaller works, see a postcoital Neel in bed with her lover or sitting on a toilet as a man with a semi-erection urinates into the sink. Elsewhere, see her rendering of one lover asleep in bed, then another of a different lover, whose penis she meticulously draws. As curator Helen Molesworth has quipped, Alice “liked dick.” The late Tom Armstrong, former director of the Whitney, once said, “She would find ways to say ‘penis’ about every fifth word.”

While the male-dominated art world refused to notice Neel, she made a clear point of noticing men, sparing nothing in her depictions of them, showing her desire, disdain, and boldness as few had before. When a whole new art world erupted in New York in the 1950s and abstract expressionism took the global stage, Neel was passed over. She said abstraction “pushed all the other pushcarts off the street.” In the late ’50s and ’60s, other movements took hold, but Neel was never included; she watched as fellow figurative artists — male peers like Alex Katz, Fairfield Porter, Philip Pearlstein, and Lucian Freud — came to prominence. Perhaps if Neel had been the grandson of a famous psychoanalyst (or, at the very least, a man), she would have been given her due. It must have been galling.

In 1959, at the suggestion of her shrink, Neel screwed up her courage and began asking downtown art-world figures to sit for her in her living room studio, first at 21 East 108th street and then at 300 West 107th Street. (She had moved uptown in 1938, for good.) Neel’s portraits of the 1960s and 1970s are peopled with incredible, crested human bouquets. Some have sepulchral eyes. Others radiate neediness, raw nerves, boredom, creativity, pathos, helplessness, or the splendor of a new cultural world. She painted trans performers, famous writers and critics, soldiers, museum guards, and alpha curators. In 1970 she painted the greatest portrait ever made of Andy Warhol, which is on view at the Met: Rather than the cool character with sunglasses, Neel gives us Auntie Andy, seated — almost hovering — on a barely sketched-in bench, stripped naked to the waist, wig amuss, eyes closed, face rutted, with sagging breasts, scars, sutures, and corset visible. His frail baby-seal body is sunken, blown to pieces, and stitched together. (He had been shot by Valerie Solanas two years before.) This is Warhol as wraith, as wounded, introverted angel. What ties these two artists together is that they and their work survived off the charismas, frailties, and fantasies of others.

Neel knew exactly what she was doing in these uptown sitting sessions — I think of this setting as her “Factory.” She was preserving, pinning, and vivisecting these personages like insect specimens, devouring them for her own ends. (Are these revenge pictures?) Her sitters range from orchids like Warhol to poet-curator Frank O’Hara; artists like Robert Smithson and Benny Andrews; famous civil-rights workers like James Farmer, who organized the first Freedom Ride in 1961; and notable critics Cindy Nemser and John Perreault (who said Neel made his penis bigger than it actually was). These sessions still didn’t gain her the recognition she deserved. When she painted Met curator Henry Geldzahler in 1967, Neel ventured that maybe he’d include her in an upcoming show. It must have killed her when he coolly replied, “Oh, so you want to be a professional?”

Finally, in 1974, at the age of 74, Neel had a retrospective at the Whitney Museum. The show was up for 38 days. It had an eight-page catalog with one color illustration. No sooner had the show opened than New York Times critic Hilton Kramer blasted her as “not the kind of artist whose work can sustain such scrutiny.” He scoffed at her “ineptitudes” and wondered “why so many serious people lend themselves to this unflattering treatment.” He couldn’t stomach that she didn’t paint conventionally beautiful people in conventional ways, that her figures had either large or shrunken heads, beady eyes, stunted and elongated bodies with foreshortened limbs or gnarled hands. He later sniffed that she merely loved “playing the role of the sassy old lady” and scoffed that “Alice — as I shall refer to her … waited until she was a geriatric ruin herself before attempting her first self-portrait at the age of 80 … in the nude, of course.” Another Times critic, James R. Mellow, cracked that her work was “savage.”

How “savage”? Neel’s nude self-portrait stands with Picasso’s 1905–6 portrait of Gertrude Stein. In each we see a Gibraltar-like woman — monumental, aware, in thought, and with power. Neel said “I hate the way I looked … I don’t like my type … my spirit looked nothing like my body.” She still revealed it all, picturing herself naked and old in her living room, a human animal with a prehensile toe, breasts resting on stomach, “flesh dropping off my bones,” holding a paintbrush (“I live for this little thing in my hand”). Picasso’s Stein may be Mesopotamian mountain; Neel is the allness of a knowing Buddha, a portrait of spirit and body as cosmos. This painting is hung near the end of the Met show: By the time you see it, you know that Neel used that “little thing” in her hand as a stick of dynamite.

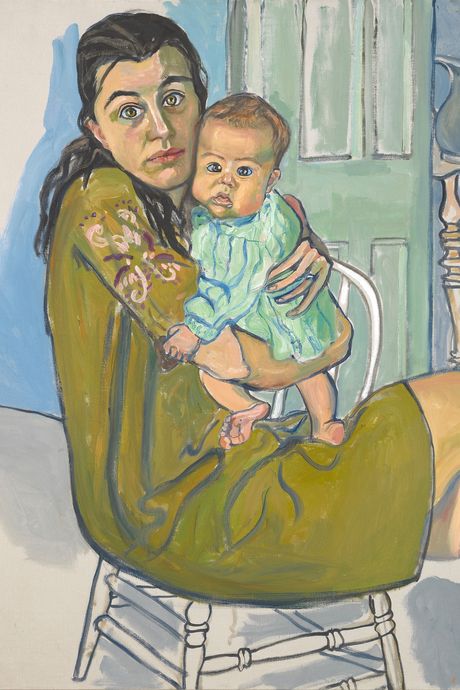

Neel’s painting of her own body capped decades of female nudes painted in ways that no man had ever painted them before. Neel gives us women as real, feeling everyday Atlases: living, dying, sexual. These are not the romantic, damaged, fragile, venomous, or hysterical objects of the male mind. No one in all of art has ever surpassed Neel’s paintings of pregnant women, childbirth (her 1939 work Childbirth is the only painting I know of the subject), and mothers with children. These works are tidal forces unto themselves. This is a true meaning of “flesh of my flesh.” Neel’s colossal images are a singular document of the eternal cosmic topology of motherhood.

In Childbirth we see a woman in labor, at the mercy of the fates, becoming the artificer of a new universe. The picture is mostly brown and black and has the strumming power, clattering dark shadows, and internal disjunction of a cave painting. A woman with enormous swollen breasts and nipples and a massive bloated belly, legs twisting and arms flailing, with one of her palms facing forward as if in imploring supplication, ogling us with her giant eyes. This is a picture of her friend Goldie Goldwasser, with whom Neel shared a maternity ward — and we may also see it as a self-portrait, both furnace and slaughterhouse, inferno and creation.

Pregnant Maria (1964) gives us a hugely pregnant supine woman on a bed — so confrontational, voluptuous, and challenging that we may think of it as Neel’s answer to Manet’s Olympia. Margaret Evans Pregnant, the first painting inside Neel’s Met exhibition, slaps you alert. Neel made this work in 1978, at the apex of her powers, as in control of her craft as Ingres was in his last great portraits. Margaret’s arms extend straight down as she barely balances on a low, uncomfortable chair, her stomach so enormous it seems to split her upper and lower body; her profile in a nearby mirror recalls the way Neel depicted her own face in Well Baby Clinic. She looks straight at us clear-eyed, in control, yet uncomfortable and ambivalent about motherhood as any human being would be. This ambivalence was never rendered quite this way before.

In Pregnant Julie and Algis (1967) and Pregnant Woman (1971), nude pregnant women are shown lying down, barely able to move. Each has a husband or male partner nearby (one is shown as just a portrait in the background) but there’s no mistaking that the men pictured are materially and spiritually outside these women’s kingdoms of existence. The men are drones. The women as the suns of new solar systems.

Finally, there are Neel’s many pictures of young mothers nursing or with their children. Here we see the new dominion these women live in. These paintings impart a wisdom gleaned elsewhere, only in Old Master pictures of the Virgin Mary with her child. Mary had terrible foreknowledge of what was to come; the faces of Neel’s mothers have that same look. We can see in their expressions signs of sadness, remorse, despair, incredulity, fear — as well as the dawning acceptance that their love now exists outside their body and will grow up, become its own ark, do things on its own, and that they will not be able to protect it. That this child will one day die.

Author Tillie Olsen wrote about this chasm between mother and child in her 1961 short story “I Stand Here Ironing”: “You think because I am her mother I have a key, or that in some way you could use me as a key? … There is all that life that has happened outside of me, beyond me.” Neel’s mothers know this doom. And this feeling never goes away. In the 1970s, Neel still seems shaken, speaking to an interviewer about, “the tragedy of losing [my children]. Everything. Everything.” Neel’s mothers look at their children in such a way that we know that they have divided souls — they give up control with the knowledge that they are bound forever to this being, one who might also tear them away from their own work or life or peace. We cannot put into words what this knowledge is. Sappho allegedly wrote that “What cannot be said will be wept.” That is what I see in these paintings.

Experiencing Neel’s work at the Met — after a full year of loss and social upheaval — her gigantic vision, perseverance, and the tragedies of her life tell us that we could be heroes like her and the people she painted. It’s easy to recognize her greatness in retrospect, when her work is celebrated in a setting like this. For most of Neel’s 84 years, though, she was artistically on her own. “I broke all the rules,” she said.