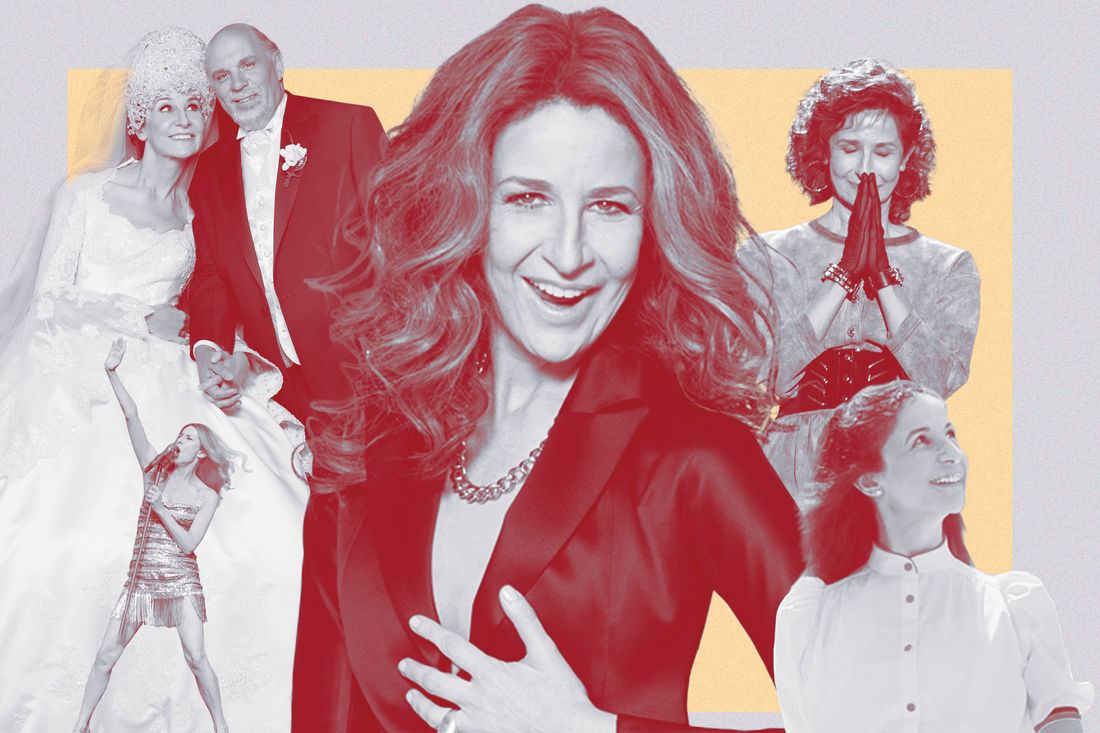

The film Aline, which premiered last year at Cannes to an audience both baffled and delighted and was deemed “scary” by The Guardian ahead of its wide release, defies simple explanation. It is about a woman who looks and acts and sounds like Céline Dion. This woman’s life includes many of Dion’s own pivotal moments: discovery as a gawky but preternaturally talented young girl by a much-older manager who becomes her ponytailed husband; a “makeover” and ascendancy to international superstardom; a Titanic performance at the Oscars; a Vegas residency. But here, her name is Aline Dieu and she is played in a César-winning performance by French writer-director-star Valérie Lemercier at every stage of her life — including at age 5, shrunk down and warbling at a family wedding. If Lemercier had gotten her way, she would have even played Aline as an infant.

Lemercier, a Dion obsessive who co-wrote the film with her frequent collaborator, Brigitte Buc, says Aline was “freely inspired” by Dion’s life, although she takes some strange creative liberties with it: scenes where Aline gets lost inside her own massive Vegas villa or reveals a long-awaited pregnancy by carving the letters BB into a bowl of her husband’s carrot purée with her hands. She pitches her performance somewhere between earnest homage and campy imitation, mimicking Dion’s spontaneous limb-flinging dance moves and wide-eyed energy. But she insists she is not making fun of Aline or Céline — instead, she sees Aline as a tribute to a fellow artist grappling with the highs and lows of stardom. Though Lemercier is relatively unknown to American audiences, she’s well known in France as a film actor, director and stage performer. (She’s also no stranger to celebrity impressions; she made a satirical film inspired by Princess Diana and Prince Charles in 2005 called Palais Royal!) “I wanted to speak about the artist’s life, which is also mine,” says Lemercier. “You’re alone onstage. You’re alone afterward. You’re alone when you go out. The changing rooms in the theaters are awful. There are no windows. It’s not very glamorous. I wanted to speak about all of that.”

You take some artistic liberties with Céline Dion’s life, starting with her name. Why didn’t you want to do a straight biopic?

I changed the name first. My co-writer said to me, “Change the name. It will all be easier.” And, in fact, it was. Céline’s younger than me. She’s alive. Of course, she’s much more famous than me — I couldn’t have a poster with my head and the words Céline Dion. It’s too far from the truth. I changed her name to be more free. And I preferred to make small digressions. To make a movie, you need strong images and symbols. For example, her father gives her a coin at the beginning of the movie that she carries with her all over the place — it’s not totally a fact. It’s between something true and something untrue.

When did you first become a Céline fan?

Céline has been famous in France since she was about 14 years old, but I heard about her late: I was doing a play in 1995, and there was a girl working at the theater who always sang Céline’s album D’eux while she was giving out tickets and seating people. I didn’t know anything about Céline’s life or her love story. Just the beautiful songs. I didn’t even know her English repertoire. But then I was very touched by the first images of her walking alone after her husband René Angélil’s funeral in 2016. I saw Céline onstage for the first time while I was writing the script. I was really struck by the performance, by the voice.

It sounds like you were less drawn to her talent and celebrity and more to the story behind it, the people around her.

It’s a movie for her and for René. There are books this thick on René and her mother — bigger than the ones about Céline. There was so much material: the love story, the family story, the success story.

I was very touched by that big family of Céline’s — that they’re so close. The love story with her mother is really important. Céline wasn’t supposed to be on Earth. [Editor’s note: Dion was the surprise 14th child in her family, born when her mother was in her 40s.] Everything is a plus, everything is a gift, because she wasn’t supposed to live. So her mother did twice more for her last little girl than for all her other children. She wanted to repair something. And when Céline arrived in René’s life, he had no artists, no job. I think the movie is a story about repair.

Have you met Céline before or since the movie?

No. I’d like to. The first thing I did when I finished the script was to give it to her French manager, who read it on a plane. She liked it and said, “I see how much you love her.” But Céline didn’t want to read it. She doesn’t want to see the pictures of our actors or be part of it. I understand why she prefers to not see the movie. I hope she will see it one day. Because, of course, I did it for her.

If her manager had said, “I don’t like this,” would you still have made the movie? Did you feel like you needed that permission?

It would have been difficult. In Quebec, there are a lot of comedians who love to make fun of the age difference between her and René. People were waiting for me to be sarcastic in the movie, maybe even more than the five movies I’ve made before. But that was not the story I wanted to tell. I wrote it as an homage.

Dieu means “God” in French. Was that a bit of a wink, a joke about her elevated status?

No. It was not a joke. It’s just close to Dion. Some people really are named Dieu.

What were some other details you invented? For example: Did René actually propose to Céline by putting a ring inside an ice-cream cone?

No. In the film, she meets him just after she goes ice-skating, wearing her mother’s gigantic shoes. She was not ice-skating right before she met him. I think she had normal shoes on in real life. But I wanted to explain why she has 10,000 pairs of shoes. I thought, Maybe if for the first important meeting of her life, she has bad shoes, maybe afterward she has too many shoes. It’s small things to understand her better. And it’s also a comedy, so I wanted funny things that were not bad for her.

What made you decide, I’m not only going to write this, but I’m going to direct it and star in it and even play her at age 5?

When Aline doesn’t know how to be a woman, how to dance, when she has the wrong teeth — when she’s in the dentist’s chair with an open mouth — I didn’t want to make a small girl do that. It’s fine to laugh about my own maladroit. I think it’s not funny to do that to a poor little girl.

So you decided instead, Okay, I’m gonna shrink myself.

It’s not my own face on a child’s body. It’s all me. When I’m at school, they put me at a big desk with papers bigger than normal ones and a big pen. When I’m signing records, we used big records. And we took off my wrinkles. Onstage, I’ve played a lot of kids and teenagers. It’s one of the things I love to do. Of course, it could be strange for Americans, because you don’t know me. But in France, they know I’ve played that kind of character. So maybe it’s more funny for us.

I will tell you: At first I also wanted to play her at 6 months old, as a baby with one tooth, sleeping in a drawer. My producer asked me to take that out. One time I will show it to you. Because it was so funny. For me, it’s a big regret that it’s not in the movie.

I wondered whether you’d done it as a way to make the relationship between Aline and her manager turned husband Guy-Claude — the stand-in for René Angélil — a little more palatable. In real life you and the actor, Sylvain Marcel, are close to the same age.

Yes, maybe it was better for the love story. They met when she was 12. Probably if I cast a small girl, it would be more embarrassing. The first night they sleep together, people said, “Ooh, this sequence is very strange.” I said, “Remember, we are both 55! Sylvain is older than me by ten months.”

There’s a theme running throughout the film about Aline being physically awkward; someone refers to her as “weird face, no grace.” There’s a makeover montage and a lot of conversation about her looks and the need to “fix” them. How did you address that in a way that didn’t feel insulting to you or to Céline?

I was not a nice-looking little girl. I was in the countryside, and a lot of children looked the same, and I did not. It touched me a lot at the beginning, when Céline tried to be sexy, tried to stick out her tongue, tried to be a woman, and did too much — too much hair, too much everything. But she became a butterfly. Her mother said, “You’re the most beautiful little girl.” And René told her all the time that she was the best. If you become beautiful, it’s because of the love of the people who have confidence in you. This is another reason I wanted to play her: I wanted to hear those things, to say that to a real little girl version of me.

You really embody Céline’s natural wackiness. She is a kooky person, and the tone of the film feels like it’s on the same wavelength as her sense of humor.

She’s a clown.

Can you talk to me about finding that tone? Because it’s a fine line — you’re not making fun of her.

I think we did that in editing. The script was funnier, more of a comedy. But I wanted to mix funny and sensitive. We know all along that Guy-Claude is going to die. The day we edited the death, I came back very sad. It felt like it happened to me. It was difficult.

A lot of Céline Dion’s bigger hits, like “The Power of Love” and “All Coming Back to Me Now,” are missing from the film. But you do have a lot of her bigger covers, like “River Deep, Mountain High” and “Nature Boy.” Were you unable to get the rights to some of those other songs?

All the songs I chose speak about her love. Each is a step of her love story. And at the end, she’s alone, and there is only one song she sings from the beginning to the end, that last song: “Ordinaire.” That really speaks to who she is. I didn’t have the rights to “The Power of Love.” The legend who wrote the song didn’t like me to have that song. It was the only song I couldn’t have. We have “I’m Alive,” we have “My Heart Will Go On,” and there are some important French songs, like “Pour Que Tu M’aimes Encore.”

Victoria Sio provides Aline’s singing voice. How did you work together to get her to sound so similar to Céline?

We had 50 singers to choose from. It was like The Voice with no names attached. She was letter B, and she was really the best. They told me, “She works a lot. She will be easy to direct,” and that was the case. Of course, she was obliged to sound near to Céline, but I wanted to hear her heart. I wanted her to be in the song. I think she had the most difficult job of that movie, to make 16 songs. They’re not complete in the movie, but we did it for the record.

What was the process of matching up your performances to her vocals? Did you lip-sync to her?

She was singing to match me. She has the lyrics, she has my face, she must breathe like me, she must move like me. All of that. In certain songs, you can hear my voice mixed with her voice for a few moments.

So when you filmed those concert scenes, were you singing in front of an audience or lip-syncing to another track?

I was singing for real in a stadium with nobody in front of me. I was alone in 22-centimeter heels. And I was crying. I was really in the songs. I was totally, 100 percent in the songs.

How did you mimic her physicality?

I watched tons of videos. I would watch, watch, watch Céline. I never worked with anybody, and I never saw myself in the mirror. Céline’s movements are so characteristic and not so difficult to do. It was in my body. It was the same when I played her as a baby in a drawer: I spent two or three hours before the shoot, watching videos of babies.

I didn’t work with a choreographer except for when she’s singing that Tina Turner song: When I was a little girl …

“River Deep, Mountain High.”

I had to work with a choreographer for that song, because we were dancing and we had a lot of rehearsal. But the other songs, I did alone. I was in her head and her body, and I know how strong she was. I am not so far from her physically. I’m taller, and I am probably bigger, but it’s not too contrary. When I saw a picture of me as a small little girl, we really are the same. We have the same big nose, small mouth, big arms, big hands, feet. I couldn’t play another singer.

In some of the press you’ve done abroad, you’ve spoken about Quebec’s protectiveness of Céline as an export and about how you asked actors not to use too many Québécois expressions. Why were you so concerned about that?

All of the actors in Aline are from Quebec, which made people in France afraid because they are not known in France. Also, although we speak the same language, we don’t always put things the same way. As you may know, Québécois movies come to France with subtitles — even Xavier Dolan’s. I didn’t want to put subtitles, which I would have to do if I kept in too many Québécois words, and that’s not possible for something that needs to be funny. So we reached a compromise: I asked the Québécois actors to speak as if they were more French. If you put in the real expressions from Quebec, it would be too distracting. I don’t speak about maple syrup. I didn’t want to have any limitations for Céline.

And you were concerned about showing this film to different audiences: French, Quebec, American. What were you expecting the reaction to be, and what did it end up being?

Different everywhere. In Portugal, there was laughing all the time. They know less Celine than us. It really was funny — even at Guy-Claude’s death, there was laughing. The Japanese are very crazy about the little girl. At first I was very alarmed, because it was the first time and maybe the last time of my life to have a movie released in the USA. I don’t want to be loved, I just want to be understood. I love that you understand what I wanted to say: the fantasy I wanted to put in the movie, the delicatesse.

I heard two of Céline’s siblings thought the film was disrespectful because it painted her as growing up in squalor. What’s your reaction to that?

It’s difficult to say. We proposed to the Quebec distributor to have the family see the movie — all of her brothers and sisters. And they didn’t want to. Then one journalist let them enter a press screening under another name, and they left before the movie ended. Of course, they didn’t recognize Céline in the film. Because not everything is true. I think it’s very difficult when you’re so close. Aline’s house is not exactly the same as Céline’s. I know she didn’t leave her house through a window wearing her wedding dress.

I never wanted to be unkind. I spent all my energy to make her onscreen family a good family with love. I did get some advice while I was making the film from one of Céline’s other siblings, but he didn’t speak publicly, so I can’t say his name. René’s family loves the movie.

Céline and René’s son, René-Charles, requested a copy of the film. Have you heard from him?

We gave something to him but I have no news.

What would you say if you could meet Céline now?

First I’d say, “You have nice shoes.” And afterward, we’ll see.