He always seemed to be in a good mood, and he was always available to help with a problem or share a laugh. But nothing about Bob McGrath was forced. Like his fellow adult castmates on Sesame Street, he had old-school showbiz skills and knew how to crank up the stage energy, but he used that power sparingly. Less was more on Sesame Street. His even-keeled energy, bright smile, and ability to listen as if he really meant it had a calming influence on multiple generations of children — including young viewers like this writer, who lacked day-to-day examples of healthy interactions between children and parental figures but found them on public TV for an hour or two each weekday.

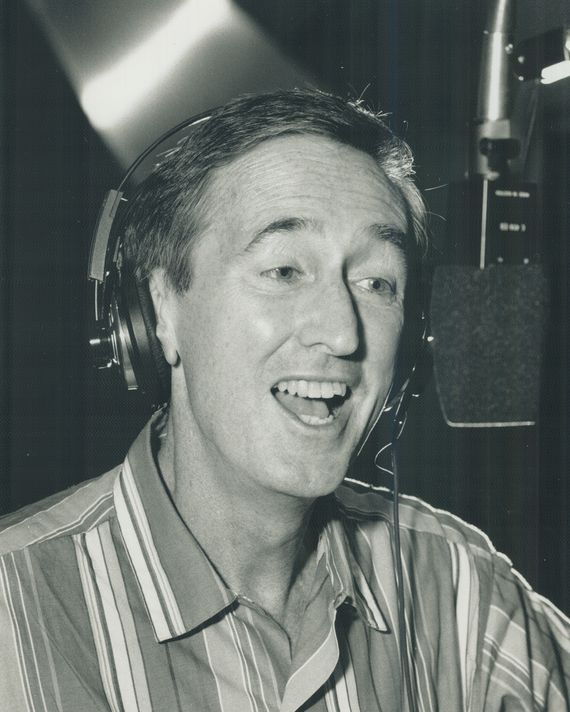

Bob (it seems wrong to refer to him as “McGrath”) died Sunday of a stroke at 90 in his home in Norwood, New Jersey. He was a gifted musician, singer, actor, and public speaker who spent more than 60 years in entertainment, including stints as a chorus member and soloist on Sing Along With Mitch and tours as a novelty act in Japan, where he sang Irish folk songs in Japanese. Throughout the second half of his career, Bob served as one of a handful of adults mixed in with the Muppet and human children of Sesame Street, incarnating the show’s guiding principles of empathy, inclusion, and curiosity as much as Ernie, Bert, and Big Bird. He debuted on the enduring PBS series as sweet-spirited music teacher Bob Johnson during its pilot episode in 1969 and played the role for 45 seasons, until he was laid off when HBO bought Sesame Street from its parent company in 2016. (He returned for a reunion special in 2019.)

Everyone appreciates the genius of the Sesame Street Muppets created and performed by masters such as Jim Henson and Frank Oz, but human regulars like Bob bridged the puppetry and various animated and musical and guest segments, knitting them together. The original pilot kept the Muppets and the “real world” neighborhood scenes separate, but after audience research determined that children’s interest flagged when puppets weren’t onscreen, series creator Joan Ganz Cooney decided to integrate them. That required a certain delicacy of performance that hadn’t been asked of actors before, but Sesame Street’s human cast nailed it by observing the primary rule of Henson’s aesthetic: When you’re talking to a Muppet, just assume you’re talking to a person in real life.

The adults’ performances didn’t just sell the puppet slapstick and character work. It also made the show’s optimistically harmonious vision of urban American life seem like a future that could actually exist, if only we could all agree to cooperate and make it happen. Bob and his fellow Sesame Street denizens were some of the “People in Your Neighborhood” immortalized by Bob in one of the show’s most famous musical numbers — and one of the earliest examples of the genius of Sesame Street’s low-key approach to human-puppet interaction. When Bob sang on the show, he was continuing a conversation; notice his laugh at the performance of the puppeteer who plays the grocer. He was often visibly delighted by what his castmates did, and his appreciation seemed spontaneous and genuine even if all the sketches were rehearsed and filmed many times. It’s the laugh of a performer who is impressed by what another actor is doing in the moment but knows how to enfold his appreciation within the fiction so as not to break the spell.

Sunny-spirited mid-20th-century kids’ shows such as Sesame Street, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and Villa Alegre (and subsequent shows in the same vein, like Blues Clues) didn’t just entertain and educate young viewers; they also offered an alternative vision of masculinity, one that wasn’t the least bit interested in dominating others, marking territory, or conflating fear with “respect.” Bob was a slender, middle-aged man with a reedy voice. He didn’t look like the sort of person who’d be of much use in a confrontation, yet he radiated a quiet assurance that suggested he could handle whatever came his way. And he didn’t make a big show of being nice. He just was.

As a kid growing up in a working-class neighborhood, in a household where drug and alcohol abuse and domestic violence were common and the emotional temperature defaulted between hot and volcanic, I loved watching performers like Bob relate to their Muppet co-stars and the child actors. Here was a world where adult men and women treated one another and children as equals, the latter needing just a bit more care where they lacked self-sufficiency. On Sesame Street, children were not burdens, inconveniences, afterthoughts, or marginal details in an otherwise adult story. They were fully dimensional people with needs, dreams, fears, and problems that deserved full attention. On Sesame Street, the adults had no agenda other than to learn about what others were feeling and — if the answer was sad, angry, confused, jealous, bitter, or lost — to help them feel better. Characters like Bob didn’t treat uncomfortable emotions as “bad,” much less as inconveniences. Counseling someone with a younger, less developed mind wasn’t an interruption to life; it was part of it. This was a lesson for viewers of all ages: Children saw healthy, respectful interactions with grown-ups; adults (and not just parents!) learned how to behave with children. And maybe with other adults too.

This is an important aspect of Sesame Street’s legacy. Even well-intentioned adults can’t bring their parental A game all the time; they will be preoccupied or rush through things, as if they wanted to get the interaction over and resume focus on themselves. So Sesame Street’s human adults served as parents, teachers, and developmental gurus, but always in the guise of as everyday folks, not magical helpers or walking instruction manuals. Instead of presenting new solutions, they suggested tools children already had, so we could problem-solve on our own next time. And they showed us how to give others what they needed when they were troubled or struggling. Many of us would’ve never seen that kind of behavior without shows like Sesame Street.

This is why Bob was the perfect person to put the death of Mr. Hooper (Will Lee) into perspective for Big Bird. As incarnated by the great puppeteer Caroll Spinney, Big Bird didn’t know or understand much. His emotions were meant to mimic a 6-year-old’s; his grief was delicate. Children’s television has changed a lot since this episode aired in 1983, so it’s not easy to convey how striking it was when Sesame Street decided to deal with Lee’s death within the context of the show rather than tell viewers the store owner moved to another state to spend time with his grandchildren or some other evasion of reality.

Big Bird says that, without Mr. Hooper, Sesame Street “won’t be the same.” Bob responds, “You’re right, Big Bird,” then rises from his chair and walks over to stand by the Muppet’s side. He delivers a brief eulogy that’s a model of sincere, unforced emotion. His voice catches as he speaks, and it feels wholly organic. This is hard for Bob, but he’s pushing through, letting the moment be whatever it’s going to be.

“It will never be the same around here without him,” Bob says, trying to be strong for Big Bird while acknowledging his own pain. “But you know something? We will all be very glad that we had a chance to be with him, and to know him, and to love him a lot when he was here.”

It’s one brief moment on a children’s TV series, but the effect is transformational: an adult man giving himself over to grief in the presence of a child without either falling apart or falsely conflating “strength” with the suppression of emotion. It’s a tricky balancing act, and we see Bob managing it imperfectly. The imperfections make the moment indelible and profound. Feelings are real. We all have them. It’s okay to show them, and it’s okay not to know what to do with them. That’s what Bob communicates in this scene — to Big Bird and to viewers of all ages.