This list was previously published and has been updated for 2023.

Don’t let the day off and the parties fool you. The legacy of Juneteenth — Juneteenth National Independence Day, Jubilee Day, Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, Black Independence Day, if you will— is much more than an opportunity to barbecue. In fact, it’s a day that ought to unsettle our comforts.

The history goes as follows: On June 19, 1865, more than two years after Abraham Lincoln manumitted all enslaved people in the Confederate states, Union Army general Gordon Granger announced the news of freedom to enslaved people in Texas, making them the last in the formerly Confederate South to get word of emancipation. The next year, beginning in the Black churches of Galveston, Texas, Juneteenth began as an observation and celebration of this belated end to bondage. The fine print: This commemoration of slavery’s end is a lesson in how its power persisted.

In the two years since this Black Texan celebration became a federal holiday recognized by the Biden administration, concerns regarding the integrity of the holiday linger as corporations, institutions, politicians, and communities continue to determine their relationships to Juneteenth, its history, political appeal, and profitability. With the much disparaged Juneteenth ice cream, themed watermelon salads, decorations, and trademark wars behind us, this year’s Juneteenth controversies have primarily concerned the holiday’s institutional and representational life.

In the past few weeks leading up to June 19, a number of stories have appeared in the news surrounding Juneteenth conflicts. A South Carolina–based nonprofit organization received criticism for promoting a Juneteenth event banner in downtown Greenville that featured a white couple and described the holiday as “an upstate celebration of freedom, unity, and love.” Franklin, Tennessee’s alderman-at-large Gabrielle Hanson has met public scrutiny for a number of recent incidents including her call for the Nashville International Airport to withdraw its financial support from “radical agendas,” which included events like an upcoming Juneteenth festival in Franklin. Making matters even more dissonant, on June 13, the White House hosted a Juneteenth concert that included a wide range of guests, from Opal Lee, activist and “grandmother of Juneteenth,” to Coi Leray, bop star and daughter of Benzino. And on Juneteenth Day, CNN is hosting Juneteenth: A Global Celebration of Freedom. More than a mere example of the lengths organizations and politicians will go to erase history or pander to those who bear its mark, these spectacles reveal the ways that power overdetermines the terms of remembrance, representation, and redress.

This is why the holiday’s nationwide popularization, marketability, and federal recognition ultimately threaten the integrity of our Juneteenth observations. A day that ought to inspire radical resentment for lapses in liberation can easily become a symbol of captivity’s circularity. This list of Juneteenth reads was curated to support the former rather than the latter. By reading these works closely, we can begin to understand what Juneteenth really means and what its observance demands of us.

Part I

BEFORE 1863

If, as Toni Morrison has written, “nothing highlighted freedom — if it did not in fact create it — like slavery,” it would stand that our close reading of freedom must begin with the narratives of the enslaved. As they show us, it often took fugitivity (and, often, more and worse) to secure one’s freedom from the formidable grasp of captivity.

The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” by Zora Neale Hurston

It is perhaps fitting that a list dedicated to the celebration of slavery’s “official end” in the U.S. begins with the oral account of Cudjoe Lewis, long believed to be the “last” survivor of the Middle Passage. Lewis was one of more than 100 kidnapped Africans stashed in the hold of the slave ship Clotilda and smuggled from Benin to Mobile Bay, Alabama, in either 1859 or 1860 (it’s hard to say), decades after Congress’s formal 1808 ban on the importation of African slaves. Hurston tells Lewis: “I want to ask you many things. I want to know who you are and how you came to be a slave; and to what part of Africa do you belong, and how you fared as a slave, and how you have managed as a free man?” He responds: “Thankee Jesus! Somebody come ast about Cudjo! I want tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go to tell everybody whut Cudjo says, and how I come to Americky soil since de 1859 and never see my people no mo.’” Eager to be asked, Lewis shared his experience of alienation and enslavement with Hurston, whose sensitive transcriptions add a new texture to our existing archive of slave narratives.

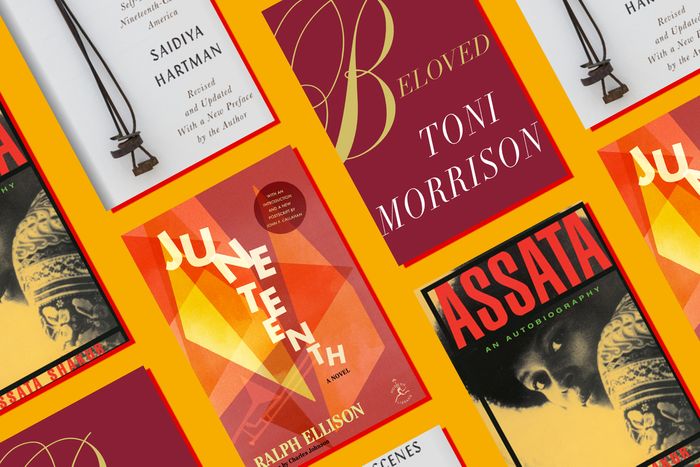

Flight to Canada, by Ishamel Reed, and Beloved, by Toni Morrison

Taking to fiction to confront the limits of and unmake our concrete understanding of slavery, the literary development of “neo-slave narratives” muddy the border between enslavement and emancipation through narratives that address the problem of self-possession. Reed’s enslaved protagonist declares, “Here I am, involuntarily, the comrade of the inanimate, but not by choice … I am property. I am a thing.” Morrison’s Sethe, a fugitive slave haunted by both slavery and freedom, understands that “freeing yourself was one thing, claiming ownership of that freed self was another.” Though these novels often explore the harrowing conditions of the peculiar institution through humor (“The devil’s country home. That’s what the South is,” one of Reed’s characters remarks) and haunting (“124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom. The women in the house knew it and so did the children,” opens Beloved), they push readers to consider the psychic toll of slavery and how its material cost to the mind defies tone and time.

Part II

FREEDOM RINGS HOLLOW

The social momentum that led to Juneteenth’s federal appropriation has transformed it into a festive footnote, a citation of American political progress that fails to ask what it means for the government to claim emancipation as a victory while many inheritors of slavery’s legacy remain dubious, if not outright disdainful. After all, for those who had been enslaved in Union states, legal and literary word of emancipation would not come until later in 1865 with the ratification of the 13th Amendment. And what did the Texas proclamation matter to the enslaved people who were held in bondage in Indian Territories until 1866 (the same year Juneteenth celebrations began)? What do we make of slavery’s resilience? How has it undergirded our freedom?

Scenes of Subjection, by Saidiya Hartman

Explicitly concerned with the elusiveness of free ground, this groundbreaking text — to be reissued later this year by W.W. Norton with a new preface by Hartman, a foreword by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, and afterwords by Marisa J. Fuentes and Sarah Haley — sets the complex stage of terror under slavery and its influence on scenes of Black self-making in the 19th century.

Calling us to consider “the nonevent of emancipation” in a country where “freedom did not abolish the lash,” Hartman frames the question of liberation on terms that center on the “terrible spectacle” of bondage that lingers in our discourses of redress, resistance, and individual rights.

The Known World, by Edward P. Jones

Jones’s historical novel follows Henry Townsend, a freeman born to former slaves, as he takes up the charge of liberty as a challenge to brutality. For Henry, freedom is best affirmed in contrast to the unfree, and thus, he dreams of running the perfect plantation — one that exceeds the standards set by the white enslavers who came before him: “Henry had always said he wanted to be a better master than any white man he had ever known. He did not understand that the kind of world he wanted to create was doomed before he had spoken the first syllable of the word master.”

On Juneteenth, by Annette Gordon-Reed

The Black Texans who created the Juneteenth holiday did so as “the celebration of the freedom of people they had actually known.” As Gordon-Reed’s work shows, this intimate and regional specificity cannot be severed from the celebration. Fusing memoir and rigorous research, the Texan author proposes a new telling of her state’s legacy, one which centers the significant influence enslaved Africans and their descendants have had on the political, geographic, and social shape of the Lone Star State.

Palmares, by Gayl Jones

In this runaway-slave narrative set in Brazil, where slavery was not abolished until 1888, Jones conjures Almeyda, an escaped slave who takes leave of her Portuguese captors to join the historic 17th-century Brazilian maroon society that the book is named for — only to discover that some still occupy the position of slaves even among the maroons. Nobrega, one of those slaves of Palmares, remarks on the contradiction, “I am not a free woman … I have no free ground to hold. Every ground I walk on is the same.” Indifferent to the fate of Palmares, whose members faced constant threats of Portuguese land conquest and reenslavement, Nobrega remarks, “Why should it matter to me if Palmares is no more?” As Jones’s novel shows, the unbound possibility of slavery beyond the plantation and the narrative of emancipation in the U.S. can be neither settled nor singularly confined to Juneteenth.

The Long Emancipation: Moving Toward Black Freedom, by Rinaldo Walcott

The issue of freedom’s lag is precisely what marks the narrative legacy of Juneteenth as precarious. Challenging the popular understanding of emancipation as a singular event that secured Black freedom, The Long Emancipation presents the issue on a global scale weighed by slavery and colonialism, in which the end of bondage could be said to be buffering at best.

Posing the “long emancipation” as a more accurate description of the chasm between freedom and manumission, Rinaldo Walcott contends that, “the conditions of Black life, past and present, work against any notion that what we inhabit in the now is freedom.”

Juneteenth, by Ralph Ellison

An incomplete manuscript that was edited and published following Ralph Ellison’s death, Juneteenth embodies the essence of “unfinished business” embedded in its title. Giving voice to a righteous skepticism about the holiday’s presumed meaning, the protagonist, a Black Baptist preacher, retorts in a sermon (at a Juneteenth gathering no less), “There’s been a heap of Juneteenths before this one and I tell you there’ll be a heap more before we’re truly free!” And though the scope of the novel is not centered on the observation of Juneteenth, its characters — a race-baiting, white-passing Black senator and the aforementioned preacher who raised him — live out the ambiguous legacy of emancipation through a complex melding of ambivalence, anguish, and ambition.

Black Age: Oceanic Lifespans and the Time of Black Life, by Habiba Ibrahim

Habiba Ibrahim’s 2021 book Black Age: Oceanic Lifespans and the Time of Black Life considers how “through the various phases of transatlantic slavery, blackness ha[s] been dispossessed of time on various scales, from bodies to histories.” Theorizing “black untimeliness” within the Black literary and film culture of the 20th and 21st centuries, Ibrahim explores representations of Black children, elders, vampires, ghosts, and more. In her reading of Jordan Peele’s 2017 film Get Out, Ibrahim draws attention to the film’s Black protagonist, Chris, and the ways that dispossession collapses the distance between his childhood and adulthood. Noting the “unaged” quality of Blackness in literature and popular culture, Ibrahim examines the unruly time card of history through narrative. The book offers an analysis of Black time and its contingencies that is invaluable for our meditations on the legacy of Juneteenth. Black Age reminds us of the ways that anti-Blackness warps temporality. As we set out to celebrate a holiday that is indivisible from slavery’s timeline of terror, books like this situate the afterlife of slavery as one marked by deadly delays, time-theft, premature death, and unaged precarity.

Part III

BETWEEN EMANCIPATION AND LIBERATION

Because the 13th Amendment to the Constitution grants the continuation of slavery through the language of penalty, no one has sharpened our collective critical eye toward the political economy that threatens emancipation like incarcerated Black writers and the stories of incarcerated people. It comes as no surprise that allegories and allusions to the structure of prison populate Black literary musings on emancipation across genre and form. Just as the prison (in figures of speech, fact, and fiction) points us to a contemporary language of slavery’s afterlife, Juneteenth invites us to read emancipation more critically and celebrate the political conviction such a reeducation demands.

American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, by Terrance Hayes

“It is not enough to love you. It is not enough to want you destroyed,” Hayes writes in this collection of seventy poems concerned with themes of American politics as they secure his own implied and impending death. Embracing the language of assassination — a murder that, owing to the influential status of its victim, gives death new meaning — his poetics work to reconstitute the meaning of a “land of the free” predicated on deadly pursuits. Speaking to violence and capture as distinguishing elements in the formation and future of the U.S., the poet names a sense of confinement at the level of the nation’s literary form: “an American sonnet that is part prison, part panic closet, a little room in a house set aflame.”

Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson, by George Jackson, and Assata: An Autobiography, by Assata Shakur

Jackson writes, “When I revolt, slavery dies with me. I refuse to pass it down again. The terms of my existence are founded on that.” Shakur likewise asserts that “after a while, people just think oppression is the normal state of things. But to become free, you have to be acutely aware of being a slave.” Framing slavery in terms of a consciousness forged by criminality, the writings of Black activists who have suffered the conditions of being “locked up,” compel us to unlock our minds toward the psychology of state violence and a legal apparatus that preserves anti-Blackness.

The Nickel Boys, by Colson Whitehead

In Colson Whitehead’s novel, inspired by the horrifically unstable distinctions between school and prison for mid-century Black youth, the teenage protagonist, Elwood, shakes his head when he listens to a 1962 recording of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s sermon at Zion Hill Baptist Church in Los Angeles. On the record, the reverend declared, “Throw us in jail, and as difficult as that is, we will still love you … We will wear you down by our capacity to suffer, and one day we will win our freedom.” For Elwood, a Black boy abused at a racist reform school, this request for love prior to liberation is unfathomable: “What a thing to ask. What an impossible thing.”

Part IV

IMAGINING FREER FUTURES

Throughout popular culture, Black creatives have made use of the language of slavery and emancipation to address their fraught relationships to their identities and crafts in industries shaped by racial capitalism. From Prince writing the word slave on his face in 1993 during a contract dispute with Warner Bros. to Anita Baker’s declaration on obtaining the masters to her albums that she’d “retired from the plantation,” the issue of freedom has shown itself foundational to the conflicts faced by Black artists who look back as they try to help create new paths forward.

The Meaning of Mariah Carey, by Mariah Carey and Michaela Angela Davis

Mariah Carey’s memoir features a comparison of her former Bedford marital home (a 33,000-square-foot mansion on 51 acres where she was plagued by anti-Black bigotry, constant surveillance, and emotional abuse) to the nearby Sing Sing Correctional Facility: “No matter how prime the real estate, how grandiose the structure, if it’s designed to monitor movement and contain the human spirit, it will only serve to diminish and demoralize those inside.” After Carey’s personal Sing Sing has burned to the ground, the R&B artist responsible for 2005’s best-selling album The Emancipation of Mimi, declares, “I have had to emancipate myself several times.” Even the most glamorous among us cannot deny the glaring fault lines in our flimsy talk of freedom.

Magical Negro, by Morgan Parker

Named after a cinematic trope coined to describe the prevalence of Black secondary characters in film whose narratives were shaped by a superhuman (if not supernatural) selflessness, the “Magical Negro” is the visual manifestation of slavery’s afterlife in myth and metaphysics.

Blending pop-culture references with a biting poetic form, Morgan Parker takes up this figure in contemporary culture as a means to assess our political imagination. In so doing, she reminds us that only after reading the world and fully realizing the stakes before us might we, as in Parker’s “Magical Negro #80: Brooklyn,” “learn to pronounce freedom.”