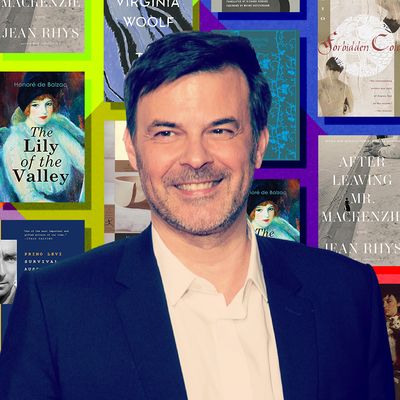

Bookseller One Grand Books has asked celebrities to name the ten titles they would take to a desert island, and it has shared the results with Vulture. Below is Summer of 85 director François Ozon’s list.

I dove into Wuthering Heights when I was 15 or 16 and read it in a single sitting, starting in the afternoon and reading late into the night. I was thrilled by the idea of passionate love. It’s a very English novel, very gothic, whereas French Romanticism is more rooted in disillusion. We had a big library in our home, and my parents let me read whatever I wanted. But I was mainly excited by the books, like this one, tucked away on the highest shelves.

I read this for school and didn’t fully understand it at the time, but I remember that I found it shocking. In contrast to Wuthering Heights, this is Romanticism in the French style. It’s the story of an older woman, Henriette de Mortsauf, and a young suitor; they have big conversations, they talk about love, but they never have sex.

A friend of mine recommended this to me in my 20s as a suggestion for a film because Rhys is so good at portraying women’s lives, all of which are in various ways portraits of herself. I love the book, I love the writing, and I love the story of Jean Rhys herself — she was obscure and unlucky in love for most of her life, and she only became famous in her 70s. For the final years of her life, she had Champagne, money, and esteem, but she complained that it had all come too late.

I love the structure of The Waves, which I read in my 20s: To make a portrait of someone who is dead, in which each character has their own point of view, felt truly radical. It’s reminiscent of the Mankiewicz movie The Barefoot Contessa, but like Marcel Proust, Woolf is a writer who would be very difficult to adapt in movies. Neither of them is as concerned with story as they are with feelings, sensations.

My mother suggested I read this when I was a teenager. I remember crying as I read the book. There is a kind of hope in his account of life in Auschwitz that makes his own life story — Levi apparently committed suicide in 1987 — all the more devastating. I was destroyed by that. This book is a little forgotten today, but if I had a child, I’d ask them to read it because it’s a lesson on life and about history and memory. I was a provocative child and took a copy of The Diary of Anne Frank with me on a school exchange trip to Germany as a 12-year-old. The son of my guest family didn’t know about the Holocaust, perhaps because he was still too young, but I later discovered that his grandfather, like many Germans of his generation, had been a Nazi.

Angel is the only book I’ve ever adapted into a movie. It’s about the ego of a writer who is utterly selfish, like a portrait of what an artist doesn’t want to become. It’s very funny, very clever, but I now think I should have made it in French.

The final volume of In Search of Lost Time functions as a key to the whole series, summarizing what has come before. You can return to Proust at any point; just a few pages can prompt reflection. It’s such a pleasure to read his descriptions of feelings, of characters. It’s like a Bible for people who love literature and probably impossible to adapt as a movie. Perhaps the only director who could have done so was Luchino Visconti, who in fact tried to make it but failed.

I read Lolita as a teenager and would love to reread it from the perspective of these times. Is it a novel in favor of pedophilia or against pedophilia? I think it’s very ambiguous, not least because the reader is in Humbert Humbert’s head. That kind of ambiguity would make it impossible to publish today.

This is a book I turn to when I am stuck or lost. As with Proust, there is always something to learn. I found it in my mother’s library. I know she was a big fan of the book, so reading it was a way to understand her.

All of Mishima’s books are exotic for Occidental people; they’re very Japanese. They also have themes of sacrifice, of guilt, of cruelty and humility, and a lot of trauma. Being gay was a big deal for Mishima, and here he describes the gay community of the 1950s and ’60s in Japan. It’s a book I’d love to adapt, but I think that’s impossible because Mishima’s widow turns down all adaptations of his work.

More From This Series

- Greta Gerwig’s 10 Favorite Books

- Michaela Coel’s 10 Favorite Books

- Viet Thanh Nguyen’s 10 Favorite Children’s Books