“We’re seeing body after body, and our Mayor Giuliani ain’t trying to see a Black man turn to John Gotti.”

—Biggie, “Everyday Struggle”

The history of New York nightlife — and, by extension, New York music — is a game of cat and mouse, of the ingenuity of smart young partyers and business owners in the face of a ceaseless wave of police and government enforcement. One party slips and the other one pounces. Rage too hard and it sparks noise complaints or violent incidents that beget harsh crackdowns. Press the venues too hard and crowds slip into DIY venues and secret after-hours spots you have to ferret out in order to regulate. This city never seems to know how to apply the right amount of pressure: from the Prohibition era, when a government ban on selling alcohol drove nightlife patrons to clandestine speakeasies and doctors were legally allowed to prescribe whiskey to patients, to the last three months of the current pandemic, when Governor Cuomo made public examples of establishments that flout his very specific guidelines for reopening, where having your liquor license suspended is as easy as neglecting to sell a sandwich alongside a beer.

It’s impossible to tell the story of developments in culture without detailing the undergirding infrastructural elements that inspired them. The birth of hip-hop is forever tethered to the fiscal crisis and gang wars of the ’70s — when parties provided both entertainment for locals who couldn’t afford the threads to get accepted into choosy disco venues and valuable peacemaking avenues for gang members warring over territory — and to the studio equipment boosted during the 1977 blackout. The same is true of the Brooklyn indie-rock explosion of the aughts, a by-product of the migration in the early years of the new millennium from lower Manhattan into (then) more affordable housing in Williamsburg and Bushwick that seemed to dovetail with the job loss and economic stagnation the city suffered post-9/11. If the growth of culture is closely tied to a city’s well-being and the cost of living, so is shrink. The Brooklyn scene cooled as high-rises sprung up on the waterfront, displacing DIY venues and running up rent. The commercial prospects of New York rap dimmed at the end of the 2000s thanks in part to a decade and a half of concerted government action.

That reality flies in the face of popular hip-hop-head logic, which suggests that New York City “fell off” as comeuppance for years of downplaying southern rap and only returned to glory as artists here embraced sounds from further down shore, and while it’s not an entirely untrue correlation, the truer story is that 20 years of pressure from two Republican mayors with lofty dreams of stamping out crime, coupled with uneven policies that hit communities of color hard throughout the ’90s and 2000s, had a demonstrable financial effect on the culture. It’s a problem we’re still dealing with. The city didn’t fall; it was pushed. Before they found themselves on opposing sides of the 2020 election, Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg were mayors of New York City who ran the five boroughs with an iron fist, cutting into crime using racialized overpolicing and regulation of noise and nightlife that patrons and owners would sometimes describe as targeting. The reverberations of these initiatives can still be felt in the city makeup today in (now dormant) luxury skyscraper apartments and in complaints from affluent transplants that the city they once knew and loved is presently dead or dying.

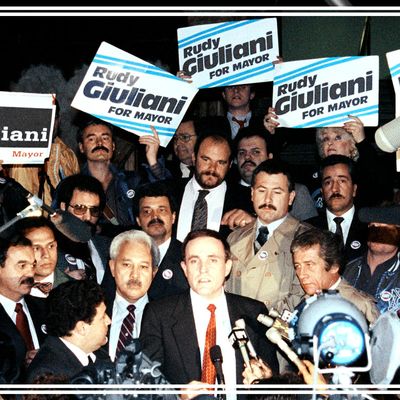

In the ’80s, as U.S. Attorney, Giuliani shot to fame after indicting the bosses of New York’s five organized crime families and jailing three for life. He rode the wave into politics and ran for mayor in 1989 but lost narrowly to Manhattan borough president David Dinkins, the city’s first Black mayor. Dinkins took office as racism divided a constituency reeling from high-profile cases like the murder of Black teen Yusuf Hawkins by a mob of white men in Bensonhurst and the arrest of the Central Park Five for crimes they didn’t commit. Attempts to balance the needs of communities in pain with rising crime rates led to harsh criticisms Giuliani would pounce on and win with when he ran again in 1993 on promises to clean up the city. His quality-of-life campaign and broken-windows policies produced results at the cost of too many arrests and too much regulation. He used zoning laws to squeeze strip clubs and adult-video stores out of residential areas, employed a draconian Prohibition-era cabaret ordinance banning dancing in clubs (a ploy to curb drinking in the ’20s) to make it harder to get and keep liquor licenses, and relied on nebulous public-nuisance laws to create trouble for noisy establishments. If the mayor or a fussy community board raised an eyebrow, you could expect a visit from the NYPD. In time, famed New York venues like Tunnel, whose Sunday nights were the stuff of hip-hop legend throughout the ’90s, closed their doors for good.

Boston native Bloomberg toiled toward a master’s in business administration in the ’60s, excelled in the ’70s at the Wall Street investment bank Salomon Brothers, and shifted into a career in data and media in the ’80s and ’90s. He entered the 2001 NYC mayoral race as a billionaire with the endorsement of Giuliani, who pivoted from public disgrace as his 2000 Senate campaign suffered under scandals — including an affair with nurse and medical exec, Judith Nathan, and his demonization of Patrick Dorismond, a Black man shot to death by an undercover officer asking him for drugs he didn’t sell (and whose lightweight juvenile criminal record was unsealed by Rudy to try and drum up favor for the shooter, who was never indicted) — to “America’s Mayor” in the wake of 9/11. Bloomberg edged out a victory and quickly set about expanding on the policies of his predecessor. His crackdowns on indoor smoking and outdoor noise spelled trouble for watering holes now generating more sound outside from cigarette breaks. He toyed with repealing the cabaret law for years, but it stayed on the books until 2017. He ramped up stop and frisk amid complaints of racial profiling, and while he promised to build affordable housing and delivered some, his courtship of big businesses ran up property values. His opposition to raising the minimum wage kept the poor in their place as the city got ritzier. Bloomberg would only change course on stop and frisk and minimum wage during his short-lived, ill-fated tenure in the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries.

Local leadership didn’t just stifle outlets where New York rappers might have gotten a leg up and make life harder in general for people of color, the pool from which most rappers here are born. It also actively pursued already famous rappers with a diligence that persists to this day. “Hip-Hop Cop” Derrick Parker tracked rappers in a subset of Giuliani-era NYPD chief Louis Anemone’s Gang Intelligence Unit tasked with monitoring crime related to rappers. In 2005, the NYPD’s hip-hop dossier leaked, listing mug shots, favored haunts, and associates of artists like Jay-Z, Busta Rhymes, and Flavor Flav. After Lil’ Kim went to jail for refusing to cooperate with police investigating a 2004 shooting outside Hot 97, surveillance of the station’s lower-Manhattan office began. Years later, we’d learn that the FBI trailed the Wu-Tang Clan from 1999 to 2004. Lil Wayne did time on Rikers Island after his tour bus, parked outside Manhattan’s Beacon Theatre on a summer night in 2007, was searched by police claiming to have smelled marijuana outside, and a loaded .40-caliber handgun was recovered.

These incidents didn’t die with the 2000s. Brooklyn rapper Bobby Shmurda went to jail after long-term surveillance of his GS9 crew and close reading of the lyrics to his 2014 hit “Hot Nigga” led to an indictment naming him as ringleader of a criminal organization responsible for shootings, murders, and gun and drug trafficking. No drugs ever surfaced; Shmurda is wrapping up a seven-year term on gun and conspiracy charges. In 2016, lower-Manhattan venue Webster Hall canceled a show by Atlanta rapper 21 Savage and caught flak for a dress code barring hats, hoodies, and baggy jeans, mirroring the language historically employed when an establishment wants to subtly discourage large Black crowds. (Webster Hall has since loosened up on the dress code.) Then, critically, after a May 2016 incident at Irving Plaza, where Brooklyn rapper Troy Ave was both shot and fired a gun at a T.I. concert, it got significantly harder to book rap shows in the city.

By June, Live Nation pulled the plug on concerts by YG, Mac Miller, Joey Bada$$, and Vince Staples, this in a month during which former NYPD commissioner William Bratton called rappers “thugs that are basically celebrating the violence that they’ve lived all their lives.” Last fall, the New York edition of the roving hip-hop festival Rolling Loud hit a snag when the NYPD pressed to have local stars like Sheff G and Pop Smoke removed from the bill, and promoters caved. It would’ve been the latter’s biggest hometown event; he was later murdered in February 2020 on the opposite coast. A mid-February hometown show at Brooklyn’s Kings Theatre, that would’ve been Pop’s last in the city, was canceled just days in advance. “Unfortunately, NYPD wouldn’t let me perform,” he said on Instagram. (TMZ says that a gang threat was his primary concern but also noted that staying away from gang members was a condition of his release on bail after a Rolls-Royce he used in a video shoot was reported as stolen by the owner in January.)

This history is no close-kept secret. It’s all in the music. “We’re seeing body after body, and our Mayor Giuliani ain’t trying to see a Black man turn to John Gotti,” Biggie rapped on Ready to Die’s “Everyday Struggle.” “Giuliani might as well be murking n - - - - -,” Jadakiss said on the LOX’s “Blood Pressure,” “’cause the time that he giving out is hurting n - - - - -.” Smif-N-Wessun went into detail on “Bucktown USA”: “First offenders are getting hit like predicates / Going through the system just for standing on the strip.” “Bloomberg banned cigarettes,” Saigon says in “Preacher.” “Why he ain’t ban letting police man beat on n - - - - - yet?” Ja Rule predicted devastation on “Believe”: “Even with the Knicks looking to make the playoffs / Spike is back on the court, and Jeter’s still with the Bronx / Bloomberg got the city ready for a séance / Go get your Ouija boards out, n - - - - -, and pray on.” Pharoahe Monch invited listeners to “flip Bloomberg the bird” on “Assassins.”

This wasn’t posturing or simple iconoclasm. It was protest music, artists outlining systemic harassment and oppression and identifying the villains in the story of New York hip-hop. The trouble never ended; like the wellspring of talent pouring out of the city over the past three years, it only got harder to sweep under a rug.