This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

I first saw Andy at openings at Dick Bellamy’s Green Gallery and at the Pop Art show at the Sidney Janis Gallery on October 31, 1962. It was the very first show of the original seven Pop artists — Warhol, Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, Segal, Wesselmann, Dine, and Indiana — and it so outraged and offended the old-guard Abstract Expressionists (de Kooning, Rothko, Motherwell, etc.) that they all resigned from the Janis Gallery in protest. It was the Halloween that changed art history.

Several days later with my friend the painter Wynn Chamberlain, I went to the opening of Andy Warhol’s first one-man show, at the Stable Gallery. It was right after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and everyone believed a nuclear war could actually happen at any moment. Gold Marilyn Monroe hung on the wall as you entered. This was it! Troy Donahue, Red Elvis, serial paintings of Campbell’s soup cans, Coke bottles, and dollar bills. Everyone in the art world was there.

I stood in the very crowded gallery, a little dazed. I knew it was better not to have complicated thoughts about the art, but to simply be with it. Experience it beyond concepts, in the very noisy room. We walked up to Andy, and Wynn said, “I’d like to introduce a young poet, Giorno.”

I took hold of Andy’s soft hand, which dangled from his wrist, and squeezed it. We looked in each other’s eyes. Something happened, a spark.

“Ohhh!” hummed Andy. I dropped his hand.

“I love the show,” said Wynn. Andy was pleased.

Over the next few months, I ran into Andy at art openings, parties, and Happenings. Sometimes I said hi to Andy, but there was almost no interaction.

Finally, in the spring of 1963, at the opening of Salvatore Scarpitta’s show at Leo Castelli Gallery (paintings of abused found objects sunk into brownish, grayish paint), Wynn said to Andy, “Come to dinner tomorrow night. John and I are going to see Yvonne Rainer at Judson Church, and we can all go together.”

“Oh, yes,” said Andy. I was surprised, as Andy and Wynn didn’t really know each other.

Beforehand, Wynn was having this small dinner in his loft on the top floor of 222 Bowery. He invited Bobo Keely, an Upper East Side friend, Andy, and me. Wynn cooked a wonderful dinner of coq au vin. We drank wine — I more glasses than anyone, and Andy almost none — and had a good time. Andy and I were getting to know each other.

The four of us rushed to Judson for the 8:30 performance.

Yvonne danced her brilliant new work. Andy and I sat next to each other, and it felt wonderful.

Afterward, saying good-bye, I said, “Good night, it’s so great being with you. We should get together?”

“What about tomorrow night?” said Andy. “There’s the premiere of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures.”

I was a little surprised at Andy’s enthusiasm. Jack had already been screening Flaming Creatures in people’s lofts, and everyone, including me, had seen it many times. It was already a cult classic. But this was the premiere, as in Hollywood premiere, which excited Andy. So, of course, I agreed.

“Here’s my telephone. Do you have a piece of paper?” Andy scribbled his number on a matchbook cover. AT9-1298. AT stood for Atwater.

The next night, Andy and I went to the midnight premiere at the Bleecker Street Cinema.

“It’s so beautiful.” Andy was really interested in Jack Smith. Jack was a genius and a mess, and always fucked everything up for himself. Andy was able to take many important ideas from Jack, which then went into the making of “Andy Warhol.” Among them, Jack coined the term “superstar.”

Andy and I started going out all the time, cultivating and embracing our own peculiar vision of New York culture.

More pivotal things occurred in 1963 than any other year, except 1968, which was the end of the ’60s. In 1962, all the Pop artists had had their first one-person shows, and in 1963, they were having their second shows and becoming more established. The Judson Dance Theater happened every Wednesday night. There were countless dance and music events.

Andy and I saw each other almost every night. We spoke on the telephone every morning and made a plan. I picked him up at his townhouse on Lexington Avenue and East 89th Street, and we went together to openings, Happenings, underground movies, and parties. There were so many things going on.

It was a sweet earthquake. I still had my job on Wall Street during the day, but it soon felt like the most important part of my life was Andy. Sexually speaking, we fell into an odd pattern: When I was drunk enough, he would blow me. Or when I was still in bed hung-over, he would call, ask me what I was wearing, and then show up. It didn’t happen that often (I was going to the baths and hooking up with other people), but there was a flow of sexual energy between us.

Andy was thinking of shooting a movie called Kiss and wasn’t sure he wanted to use Naomi Levine for the tight head shot kissing ten guys. I said, “Why don’t you have two men kissing?” Andy turned slightly away and deemed it not worthy of an answer. I was a poet from the world of William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, and we were concerned with the sexual freedom of gay men and lesbians.

“Why don’t you have two guys kissing, but like Doris Day and Rock Hudson?” Andy was silent and scornful. “Or two women?”

Andy said, “Ewww!” A week later, I asked again, and Andy sighed, “Oh, John!” which meant, Don’t you get it?

Eight years earlier, in 1955, the Bonwit Teller department store in New York had commissioned artists to create displays in its front windows on Fifth Avenue. By chance, Andy’s window was next to the window of Bob Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns; they installed them on the same night. In his design, Andy used a photograph of a gorgeous transvestite posed as a fashion model, who passed to the public as a woman.

“Bob and Jasper came and looked at what I was doing,” Andy recalled, “and laughed at me. They pointed their fingers and laughed. They were so mean!” The old-guard Abstract Expressionists had been (and still were) notoriously homophobic. Only straight guys, like themselves, were great painters. Queers, like the friends of their fag-hag wives, were not eligible. Inheriting and internalizing that loathing, gay artists like Rauschenberg and Johns didn’t talk about their sexuality and shunned homoerotic imagery in their work.

Against this, Andy was a gay man, undeniably swish, his work openly homoerotic. In the 1950s, this was daring and heroic. Andy made drawings for private view — a man’s foot and a male head with a licking tongue, and a hard dick hanging from half-opened jeans. And those made for the public were full of innuendo — portraits of drag queens, fetishistic outline drawings of sexy male feet.

Then, in 1958, he was nominated for the Tanager Gallery, an artists’ cooperative, but was turned down, rejected because he was too fey. Andy got the message and realized that being a gay artist was the kiss of death. Gay was a subculture, and a dead end; Andy wanted popular culture. To access a large commercial audience, he got rid of the gay content. In his most famous work, the homoerotic would be subverted and hidden.

That year, Jonas Mekas coined the term and invented the phenomenon called “underground cinema.” He pulled together a generation of young filmmakers by giving them venues and writing about them in his magazine, Film Culture. He rented small, run-down theaters around the city that happened to be empty for the night. Through word of mouth, everyone came. Andy and I went to the movies once, twice, or three times a week, every week for a year. There was Ron Rice’s Chumlum, Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising, pieces of Ken Jacobs’s Star Spangled to Death, a rough cut of Taylor Mead in The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man and The Flower Thief, both by Ron Rice. We saw them many times, as Jonas replayed them in different combinations, always putting the new film last, so we had to see the others over and over again. Andy and I saw Flaming Creatures at least 30 times. These films had an enormous impact on Andy. It was where he got the idea to make movies. He saw what film was, what it could be.

On a long weekend in late May 1963, Andy, Bob Indiana, Marisol, and I went up by train to Old Lyme, Connecticut, to visit Wynn. He had rented a farmhouse for the summer.

Eleanor Ward, owner of the Stable Gallery, who showed Andy, Bob, and Marisol in New York, rented an old stone icehouse on the same property. Wynn cooked a wonderful dinner, and we drank lots of wine. After dinner, Wynn served 140-proof black rum and I drank a lot. We said good night at about two o’clock.

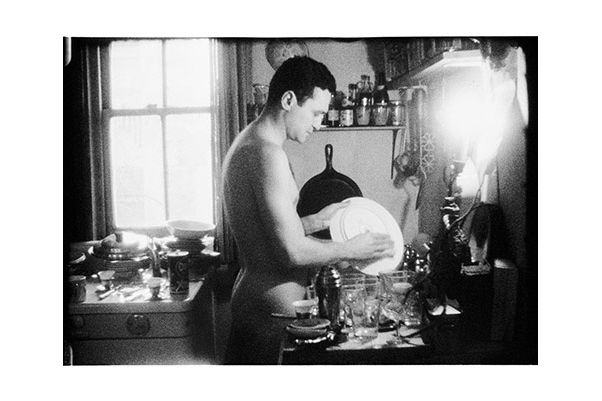

Andy and I slept in a bedroom, in the same bed, but we didn’t have sex. My brain was fried by the rum. I just dropped my clothes, fell naked onto the bed, and passed out.

I woke up about 4:30 to take a piss. In the faint traces of early-morning light, Andy was next to me, his head resting on his hand and elbow, wide-awake, looking at me. I went to the bathroom, bleary-eyed, and then back to bed.

I woke up two hours later, and Andy was still looking, his eyes open wide. “What are you doing?” I was still drunk, and confused.

“Watching you.”

I took another piss and went back to sleep. I woke after a while and he was still doing it. “What are you doing?” I had a rubber tongue.

“Watching you sleep,” said Andy sweetly.

As it became lighter, I saw him more clearly. Fifteen minutes later, I turned and he was looking at me with Bette Davis eyes. I kissed him on the cheek. “Are you okay?”

“Yes.”

“Are you sure? Take off your shirt. It’s so hot.” He declined. I tried to take it off and he giggled. Andy was wearing limp Jockey underwear. “And take off your underwear.” His skin was very white and soft, and he had hairless, beautiful boy’s legs. It was sweltering. I was wet from sweating in my sleep, so there was no thought of cuddling. I kept my eyes shut but knew he was still looking.

I woke two hours later and he wasn’t next to me. In the bright morning, he was dressed, sitting in a chair at the foot of the bed, still staring at me. “Why are you watching me?”

“Wouldn’t you like to know!”

It was not my problem that he wanted to look.

The next time I woke and looked, Andy was in bed with his clothes on, his head sunk in the pillow, drowsily looking at me. He was keeping himself up. It was 11:30 a.m. and sunlight came sharply into a corner of the room, heating it up to a tropical rain forest. Sweat poured from my body.

When I woke up at 1:30, Andy was gone. He was on amphetamines and had watched me sleep for eight hours. That night, Andy got the idea for the movie Sleep.

We went back to New York early on Monday afternoon. At the crowded Old Lyme railroad station, we waited interminably for the delayed Boston–New York train. Andy talked, as he often did, about making a movie, what he wanted to do, the kind of movie.

“Do you want to be the star?” asked Andy.

“Yes! I do!” Snuggling close, I pressed up against him like a cat. “What do I have to do? I do everything.”

“I want to make a movie of you sleeping.”

I was a bit surprised. “Great!”

“Just you sleeping.”

“I can do it.”

“I’m sure you can.”

“I want to be a movie star!” I said. It was the American Dream. I pronounced the words clearly with a downbeat.

“I know you do!” said Andy.

“I want to be like Marilyn Monroe.” She had committed suicide only nine months earlier, on August 5, 1962. Her career was tottering, and she was the failed superstar, the union of the divine and the profane. Andy had captured that in his first Marilyn paintings, done right after her death.

And I wanted that for myself. I was drawn to her suicide and her stardom.

“Oh, John!” said Andy happily.

In June, Andy talked a lot about shooting Sleep. One night after a party, he came by my place to check out my bed to see what it would look like on-camera. He examined the electrical outlets and figured out where he would set up the tripod.

I was sitting in a chair in the living room, and we were talking. Andy came over, sat down on the floor, and put his arm on my knee and his hand on my foot, and we continued talking and laughing. With both hands, he ran his fingers over my shoes. I was talking and not paying attention. All of a sudden, Andy’s face went down to the floor, and he was licking my shoes. He pressed his cheek to the leather and licked with his little pink tongue. Totally astonishing!

He had a secret reputation as a shoe fetishist; for years, he’d designed shoe ads for Bergdorf Goodman, I. Miller, and Bonwit Teller. There was Andy Warhol on his hands and knees, licking my Abercrombie & Fitch loafers. He wiggled his tongue around and smelled. My shoes were covered with saliva. It was a turn-on.

I got some poppers to make it better, but Andy declined. I took off my shoes and socks and Andy licked my feet and shrimped my toes. It wasn’t as erotic as it was deeply moving that he had allowed himself to do this. His sad, timid little tongue went around each toe. He seemed delicate and fragile.

Every once in a while, I went down and hugged him lovingly and kissed his face. Andy was trembling, and his heart was beating a mile a minute.

Several times I slipped my hand down and gently took hold of his dick, but he pushed my hand away. He did not want to allow anything reciprocal; maybe it frightened him.

I decided to cum and put him out of his misery.

On July 4, Andy and I went back up to Wynn’s Old Lyme farmhouse with Marisol and Bob Indiana. Wynn was giving Eleanor Ward a birthday party.

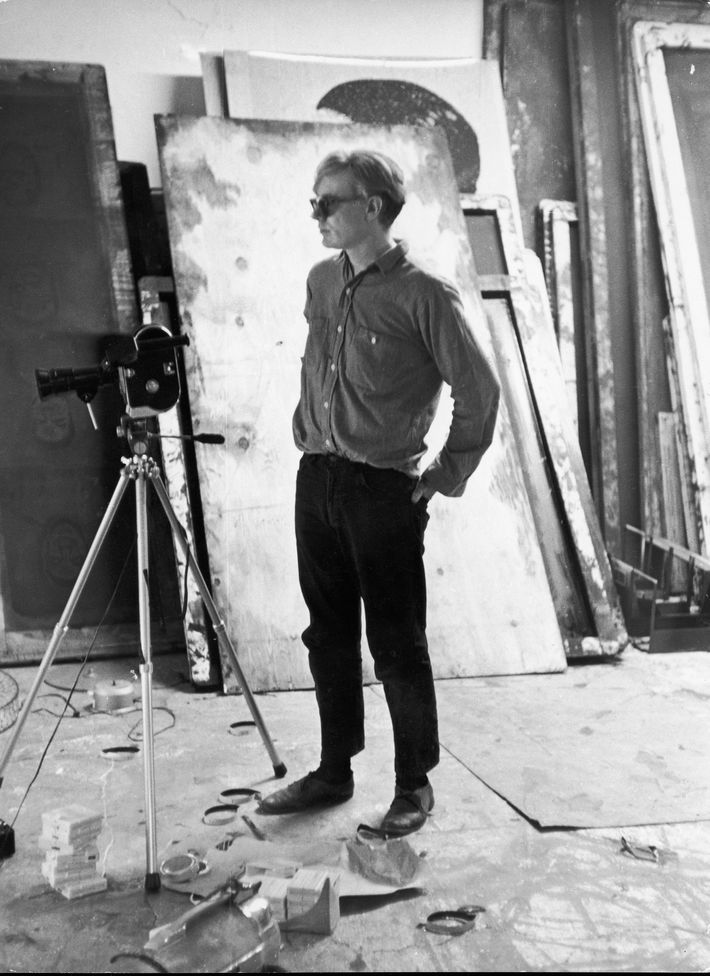

Andy also brought along his new 16-mm. Bolex. Because of the holiday, the Peerless film store had been closed so he had brought only a couple of rolls of black-and-white film. By chance, Wynn had some color film. So that weekend, Andy shot a lot in color, which he didn’t normally do. He used the film camera as if it were a still camera, which he knew how to use.

The day of the party was a hot, lazy day. We were all bored and annoyed at having to prepare for Eleanor’s birthday. I lay in a rope hammock between two trees, with my eyes closed, trying to take a nap, dazed from a hangover and the 95-degree heat. Sunlight flickered red and white on my closed eyelids, which somehow made me high. Andy was filming me from different angles. I was very comfortable with him and didn’t pay attention.

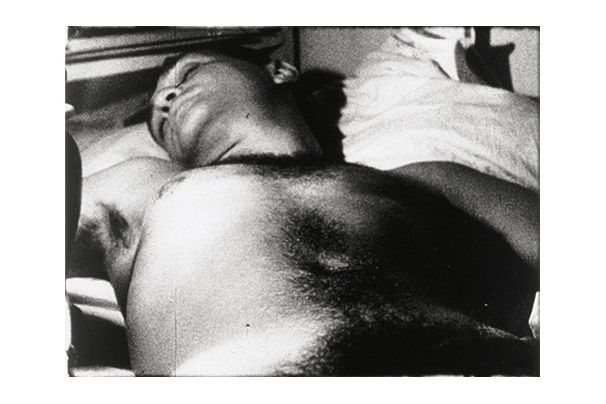

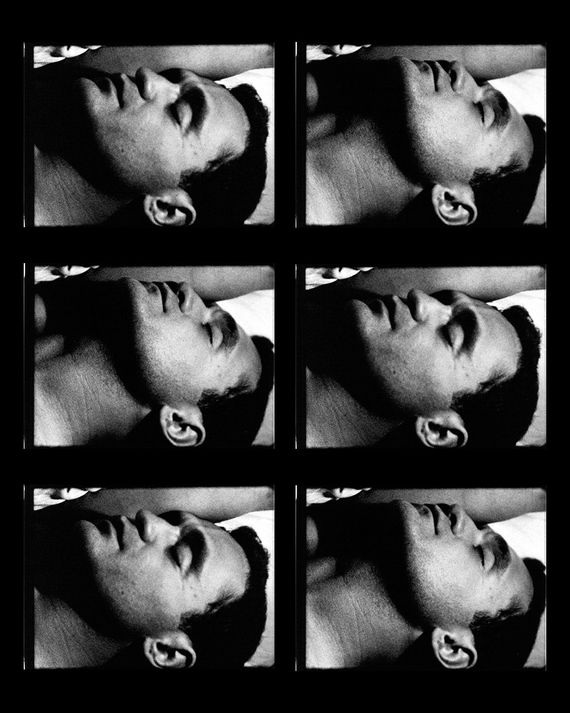

The footage of me sleeping in the hammock was beautiful — loving, very gay, everything that Andy would make sure not to include in the final cut of Sleep, which was about light and shadow. It was the one time that he could indulge himself with the pure pleasure of love. He filmed inches from my skin.

It felt like Andy was kissing or licking my skin with the camera, which is what he liked to do. He was making love to me with the camera while I slept!

We began shooting Sleep Wednesday, July 10. We had just come from a screening at the Bleecker Street Cinema and a loft party downtown. We stopped by Andy’s house and picked up the camera and lights. We got to my place and began shooting about one o’clock. I was a little drunk and made myself a vodka-and-soda. I took off my clothes, dropping them on the floor. Andy did the setup: two 150-watt aluminum reflector clip-on lights, tripod and Bolex camera, light meter and film. He was awkward and his hands trembled. He had never done it before. It was his first big film.

“Okay, let’s shoot!” I said.Andy paused, turned to me, and said, “Are you ready for your close-up?”

“Yes!” I laughed. I gave him a big hug with my naked body and pressed my soft dick into his leg.

I lay down on the bed, sank into a soft pillow, put an arm up over my head, and closed my eyes. I liked sleeping more than anything else. The movie was Andy’s problem. I let my mind rest and fell asleep immediately.

The next morning when I woke up, I saw the apartment lights were still on, and the floor was littered with dozens of crushed yellow Kodak boxes and scraps of film. Andy and the equipment were gone. And I had a hangover.

Andy shot again two nights later, and then a handful more times over the next two weeks. If our schedules were different, I left the front door unlocked and Andy came and did it while I slept. The process had an empty and caressing quality. He’d shoot for three or four hours, until about five o’clock, when the first trace of daylight came. Andy was on speed, amphetamines, when he worked — high and wide-awake. In the dead of night, everything was crystal clear.

We started over again in August, shooting Sleep for another ten days. We looked at the film on the hand-cranked movie viewer and the clacking 16-mm. projector.

“Oh, they’re so beautiful!” said Andy. It had worked. Everything Andy did was a great work of art.

There were thousands of rolls of film, and Andy didn’t know what to do with them. Every roll was from a slightly different camera angle or had a slightly different frame or light. Andy duplicated some shots that he liked, and placed them after each other and in between other shots. He was familiar with repetition from his paintings, but this repetition was out of necessity. Andy couldn’t figure out how to make the shots into a movie.

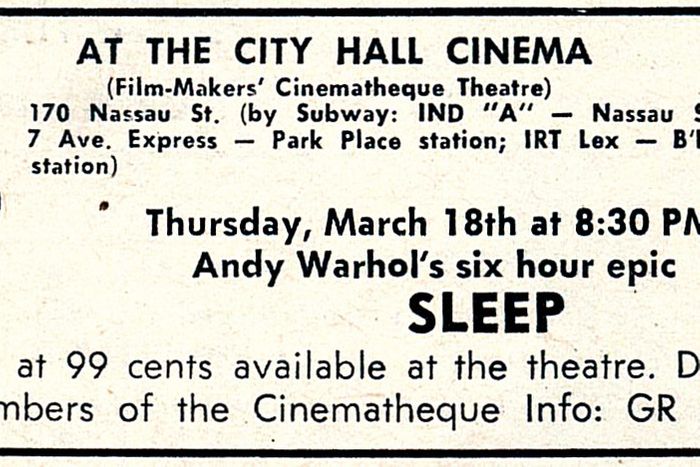

The world premiere of Sleep was on January 17, 1964, at the Gramercy Arts Theatre on East 27th Street near Lexington. The Village Voice advertisement read: “ANDY WARHOL’S EIGHT HOUR SLEEP MOVIE. Friday, Jan. 17; Sat., 18; Sun., 19; Mon., 20. Starting 8 p.m. (one show every evening). The only New York showing for some time. Contribution: $2. Benefit show for the Film-Makers’ Cooperative.”

The film ended up being five-and-a-half-hours long, not eight. Any more might have been too much.

Sleep was a great triumph. All of New York, uptown and downtown, came or had something to say about it. “You’re a star,” said Andy. “You don’t know what I’ve done for you.”

“I do! And I appreciate it,” I said, laughing. “I told you I want to be Marilyn Monroe.”

“Oh, John!” said Andy, laughing, and we leaned into each other.

On Halloween 1963, I went over to pick Andy up for a show, but as we got ready to leave, Andy said, “My mother wants to meet you.”

“What! … Why! … Great!” I was shocked. Nobody had ever laid eyes on Andy’s mother. He talked about her and was deeply attached to her, but she was a big secret. She lived on the ground floor, in an apartment behind the kitchen.

“She’s heard about you.”

“What!”

“She’s heard you on the stairs coming in and out.”

I was horrified. The night before, I had come back to his house, drunk, and when we said good night and walked down the stairs to the front door, we hugged and kissed, sloppy and affectionate.

“She heard us last night!” I gasped. “Oh, no!”

“She just wants to meet you.”

Andy took me down the back stairs in the darkness, where I had never been. It was off-limits. “Let me put on the light.” Andy knocked. His mother, Mrs. Warhola, unlocked and opened the door. “Ma, this is John.”

“Pleased to meet you!” I bowed slightly, warm and gracious as I could be.

Andy’s mother was an old woman. She had a gentle face, gray hair, a wide waist, and strong arms, and she wore a cotton floral housedress and slippers. She smiled and we laughed as we gazed at each other.

“I am very happy to meet you.”

“Good to meet you.” She was filled with loving-kindness.

Andy and his mother talked about something in what I thought was Czech. (Later, I would learn they were not Czechoslovakian but, in fact, Carpatho Rusyn, a small ethnic group from the Carpathian Mountains.)

Listening to them talk, I realized this was a very important moment. Andy introducing me to his mother was a statement, an affirmation that we were lovers. I was thrilled that it was really true. Then I said to myself, Stop thinking stupid thoughts and just be in the moment.

“You’re a good boy,” she said with an accent, smiling.

On Christmas Eve of 1963, I stopped by Andy’s house. “I have some Christmas presents for you.”

“Ohhh, no.”

“We are not exchanging gifts, but you’ve given me so much, I want to give you something. Winter solstice, New Year offerings.”

I had three presents for Andy, all wrapped in colored paper.

The first was a pair of fine black leather gloves from Brooks Brothers. “When broken in, they’ll go well with your black chinos.”

“Ohhh, they’re so … ,” said Andy, caressing them with his delicate fingers.

The second was a paper collage that I made as a Christmas card using found images, pictures from magazines, some of them pornographic, and overlaid heavily with jewels from the Tiffany catalogue. “A Rauschenberg!” laughed Andy.

“Why not!”

The third present, wrapped in white tissue paper, was a gold wedding ring. There was a pawnshop next door to 222 Bowery, one of the last surviving ones on the street. In the window, on a blue velvet tray, were 20 or 30 old gold men’s wedding rings. They always caught my eye as I went to visit Wynn. For a Christmas present, I bought one for Andy. A thick, rich, glowing yellow-gold wedding band.

“Ohhh!” Andy was shocked. “I don’t know!”

“I’m not asking you to marry me. I think it’s a really sexy gift.”

Andy looked frightened. “It’s so large, he must have had a big dick.”

I wondered if I hadn’t made a mistake. A dead man’s wedding ring or a failed marriage, but it was too late to take back.

“It’s so strong and sexy!”

“Did you get one for yourself?”

“Guys don’t wear wedding bands!” We hugged and kissed.

With a dusting of snow outside, Andy and I spent the evening together, an intimate and almost corny Christmas Eve.

We should make another movie,” I started saying to Andy after Sleep.

“Yes,” said Andy, laughing.

Time passed, and I said, “When are we going to make another movie?”

Finally, in early 1964, he said, “Let’s do another Screen Test.”

I half-thought he said it to shut me up. We had shot the first Screen Test in June 1963 and would shoot the second in March 1964. But it wasn’t enough. “Another movie idea! I want to be a movie star.”

“You are a movie star!”

I did not give up. “Andy, when are we going to make a movie?”

“There are so many ideas … What should we do? … How about Blow Job?”

“Blow Job. Yes! Brilliant! Totally great! It’s my part.”

“I thought so,” said Andy.

“You know what it looks like.”

“A tight head shot of your face, while you jerk off and cum.”

“It’s Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra.” I was thrilled. It was my role.

Time passed, and nothing happened. Andy was busy, and kept putting it off, and I kept saying encouragingly, “When are we going to shoot the movie?”

“How about Saturday? On 47th Street.”

Andy had just rented a loft on East 47th Street, the first Factory. It was still raw industrial space, a couple of months before his friend Billy Name put silver aluminum foil and silver Mylar up everywhere. There was no heat in the building on Saturdays and Sundays, which was when Andy liked to shoot, because it was quiet.

I met Andy at three o’clock on a bleak, freezing-cold Saturday afternoon in early February. The Factory was dismal. “Where are we going to do it?”

“In the back.”

We walked to the rear of the loft. There was a toilet, old and dirty, paint peeling off the walls, and graffiti. “A sleazy toilet! Andy, this looks gorgeous! It looks like a subway toilet.”

“Oh, I know!” said Andy, very pleased.

He set up the camera and lights. I smoked a joint and a cigarette and we talked. It was cold. Andy was ready.

He crouched down on his knees on the dirty concrete floor and sucked. He was nervous. I relaxed affectionately, to make it easy for him, and I put my hand behind his head.

But it turned out he’d run out of film and had just been shooting blanks. “I’m sorry. You looked so great. I couldn’t stop.” It augured bad things.

In April, Andy made Blow Job starring somebody else. I was deeply offended. How could he have done that? It was going to be my starring role, and he gave it to somebody else. I was devastated and furious but did not let it show. I couldn’t help but see it as a sign, an early death knell signaling the end of our relationship. That fall, Andy and I were supposed to meet at Castelli’s for a Roy Lichtenstein landscape show. When I got there, Andy had already left. My heart sank. This happened often: He would tell me a time to arrive, but when I got there, I would have just missed him.

Andy was tired of me. And the new Factory was full of new people pushing their way in front of the camera. Edie Sedgwick was center stage, and I was last year’s news.

On November 21, Andy Warhol’s show of Flower paintings opened at the Leo Castelli Gallery. It was his first show at Castelli, where he had moved after his show of Brillo boxes at the Stable Gallery in April. It was a well-calculated, political decision suggested and advised by Henry Geldzahler, a big move up.

The Flower paintings were Pop Art at its most pure. Brilliantly conceived, it was a popular image, which could be reproduced endlessly. Andy said he wanted to be a machine, all identity dropped, the individual gotten rid of, made anonymous. That night, I had arrived at Castelli alone. Andy and I no longer went out together.

He stopped answering my phone calls and didn’t call back. I wasn’t told about parties. And when I saw him, he acted like nothing had happened. It was heartache. I loved Andy. I was his first superstar, and I was the first one he got rid of.

Over the years, later superstars complained endlessly about Andy exploiting and getting rid of them. They spoke of his cruelty, his sadism. This was possibly true, as Andy was only human. It also might have been the result of the amphetamines. But at the time, I had no context. I couldn’t understand why it was happening, and I felt only suffering and pain.

On September 25, 1965, Andy gave a party for John Ashbery at the 47th Street Factory. The literary and art worlds anticipated it for a week, but I wasn’t invited and I was devastated. Everyone was there and talked about it endlessly afterward. Because I was a poet, it was a double insult.

Two weeks later, I ran into Andy at a party and he had the nerve to say, “Oh, you didn’t come to John Ashbery’s party.”

“I wasn’t invited.”

“I told Gerard to invite you.” That was it! I never called Andy again, not for years. I allowed my anger to blossom into big changes. Andy was dead for me. I almost never ran into him, and if I did, I avoided him or, of course, greeted him cheerfully and moved on.

Giorno died at the age of 82 last October, weeks after submitting his memoirs for publication.

Excerpted from Great Demon Kings, by John Giorno. Copyright © 2020 by Giorno Poetry Systems Institute Inc. Published by arrangement with Farrar, Straus and Giroux. All rights reserved.

*This article appears in the July 20, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!