Recently, whenever some public figure steps in it, planting foot in mouth via untoward remark or questionable endorsement, a chorus of cynics appears suggesting that our frustration with this is our own fault, as if we’re trolling for trouble having standards for celebrities beyond their core fields of expertise. “Why should we look to [insert pop star] for nuanced commentary?” “Why do you want [insert comic or actor or athlete] to inform and not just entertain?” It’s easy. It happens! Dick Gregory existed. Nina Simone existed. Harry Belafonte existed.

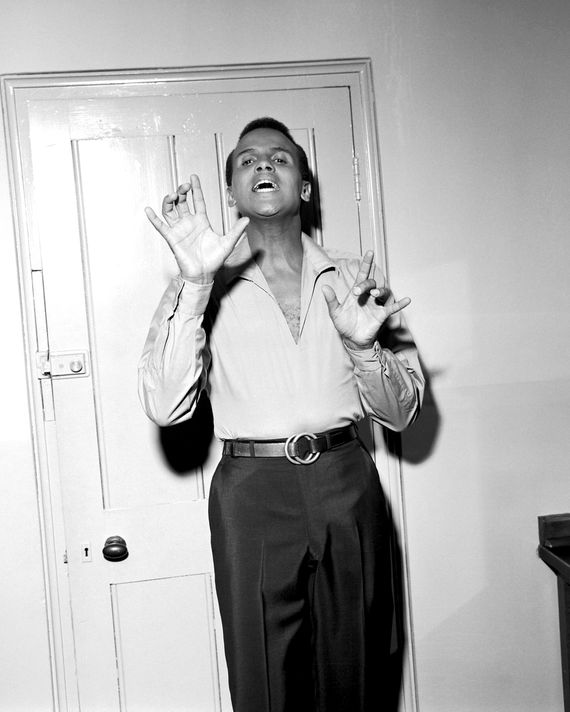

The first Black actor to win an Emmy, and the first Black man to win a Tony, and the first human of any denomination to sell a million records, Belafonte found a way amid the inequities and indignities of the 1950s to meld his polymathic gifts of acting, singing, and oration. He spoke with the burning political consciousness he developed while splitting his childhood between pre-Depression Harlem and Kingston, Jamaica, under British rule. Bearing witness to colorism and racism early on, feeling his communities bear the brunt of the fallout whenever hard times hit, the entertainment and civil-rights titan, who died on Tuesday at 96, applied himself so intently to the causes of Black upliftment, artistic integrity, and general humanitarianism that it complicated and often derailed opportunities to reach greater audiences as a performer.

Harry Belafonte could’ve cleared a mil singing whatever he wanted; the instrument was rich and pliable, capable of conveying lightness and excitement through soaring notes and lilting cadences but also blue misery in the bellowing low end. Folk felt important, as did honoring his Jamaican heritage through song, tracing lines of influence between New York and the Caribbean (the very cultural trade route that fostered the flowering of hip-hop decades later) and the rest of the world. “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song),” the hit from the history-making 1956 best-seller Calypso, contains multitudes. It’s an old work song, a celebration of the few hours’ peace squeezed out of a rough week, a tune boisterous enough for Shirley Bassey and Sarah Vaughan and also for Beetlejuice and Lil Wayne.

Dubbed the King of Calypso, Belafonte seemed to bristle at the honor, pushing past the sound of his signature track in a series of gospel, blues, and jazz albums that succeeded in establishing a lack of interest in repeating himself, both musically and on the charts. The 1959 live double album Belafonte at Carnegie Hall drives home what the artist was trying to say in those years. Split into three acts — “Moods of the American Negro,” “In the Caribbean,” and “Round the World” — the show gave a pained, triumphant voice to Black American resilience, tying it to the rich histories of art and defiance throughout the diaspora while expressing how this all resonates with the plights of other ethnic groups. Singing the migrant workers’ song “Jamaica Farewell,” the Lead Belly lament “Cotton Fields,” the Irish ballad “Danny Boy,” and the Jewish standard “Hava Nagila” laid bare the dimensionality of the struggle for equality for audiences shielded by affluence, an inkling that later led Belafonte to collaborating with the South African singer and notable apartheid critic Miriam Makeba and to coaxing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. into tapping international allies for assistance with civil-rights outreach.

The question of what to do about the white gaze as a Black auteur with a massive following informed the work Belafonte would carry out in and after the ’50s, when he acted as a liaison between Hollywood and the Black social-justice movement, nudging peers into activism and working fundraising miracles (like the perilous night in 1964 where Belafonte and his close friend Sidney Poitier narrowly escaped a Ku Klux Klan ambush while trying to deliver funds to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee following the murders of three civil-rights workers). He drove a hard bargain about positive representation for Black actors in both film and television, fostering racial unity, and bringing the arts in touch with the pressing matters in the lives of viewers and patrons. After winning an Emmy for 1959’s Revlon Revue special “Tonight with Belafonte” — which teased the 1960 full-length Swing Dat Hammer, a chilling collection of chain-gang work songs that won a Grammy in ’61, and featured stunning performances from folk legend Odetta — Belafonte signed a million-dollar deal to tape more variety nights, but he walked after being asked not to mix races on camera. “I cannot be resegregated,” he recalled telling a network exec in a 1996 talk with Henry Louis Gates Jr., while also noting that he was able to pocket $800,000.

After shining in Otto Preminger’s 1954 take on Hammerstein’s Carmen Jones, which featured an all-Black cast, he turned down a star turn in the director’s adaptation of the Gershwin musical Porgy and Bess. He felt the story made the community look bad. In those years, Belafonte declined any role he found degrading, initiating an 11-year break from a film career that never seemed to hit its stride. He found other ways to be of use. The U.S. Information Agency’s Hollywood Roundtable, filmed after the March on Washington, is a window into the prickly conversations it takes to get people to change course on rights issues. The conversation hosts astute and personal observations about growing up amid the legal racial stratification of the early 20th century from Belafonte, Poitier, and James Baldwin; words of encouragement from a typically outspoken Marlon Brando; and footage of Charlton Heston wishing he’d done more in the public eye to ease race relations (that would age awfully when he left the Democratic Party in the ’80s and antagonized rappers and eventually fronted the NRA). Asked to sit in for Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show for a week in the heat of 1968, Belafonte modeled the integrated, informed entertainment spectacle he’d been itching to create all along. He made sure to extend invitations to people like the Smothers Brothers not long before the duo was edged out of its CBS show for gestures like letting Belafonte sing “Don’t Stop the Carnival” over a backdrop of scenes from that summer’s Democratic National Convention, where the police clubbed and tear-gassed Vietnam War protesters.

Harry Belafonte might not have enjoyed the same far-reaching megawatt success, or consistently affirming box-office tallies and record sales, as peers who climbed the ladder in the same years he did. He took the prickly, insistent path instead. He brought people together while making anyone who was too at ease in the old ways of thinking a little uncomfortable, even if bristling about Black visibility in the entertainment industry and heightened political awareness from Washington to Hollywood to living rooms all over the world distanced him from opportunities to pipe down and cash out. “The movies and television weren’t all-powerful arbiters of culture,” he wrote in his 2011 autobiography My Song: A Memoir of Art, Race, and Defiance. “They just reflected the culture. Doing battle with them was like fighting a mirror. To change the culture, you had to change the country. And only one thing would change the country: the movement.”

Here in the conformist, consumerist hellscape of the new ’20s, the most nonsensical thing you can do is destroy some money, and the quickest way, now as ever, is to voice a loud and specific political stance, and the choices, now as ever, are to be annoying and illuminating or appeasing and encouraging. As bloggers and vloggers are leaning into the winds of right-wing media, and artists and influencers are boosting dicey money schemes and offshore gambling to fans who lack endorsement deals and side hustles to fall back on, and comics are invoking jester’s privilege to distance themselves from the worst messages people take from their jokes, and we’re greeting this carnival of disappointment and embarrassment with lowered expectations, let’s not forget the mountains that move whenever public sentiment lurches toward enlightenment and the many hands ceaselessly turning the gears, the thinkers and organizers and fixers and dissidents who pour their time into dragging everyone else into the future.