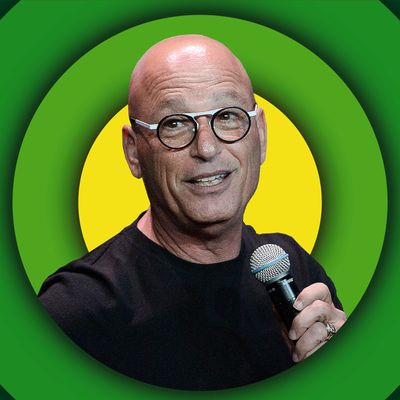

If you just know Howie Mandel as the affable, germaphobic host of Deal or No Deal or judge on America’s Got Talent, you might have certain assumptions about his stand-up. You might picture him in a 1980s comedy club, wearing an oversized blazer with the sleeves rolled up, telling some jokes about how airplane food actually tastes bad. You would be wrong. Mandel was a deeply strange, highly improvisational comedian, more likely to scream and run around than stand and deliver a polished tight five. Though it earned him a legion of die-hard fans, as Mandel tells it, it turned off certain comedians and the bookers at Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show. Mandel, however, showed them, eventually appearing on the show with Carson over 20 times.

On Vulture’s Good One podcast, Mandel, who recently launched a new podcast with his daughter called Howie Mandel Does Stuff, talks about his long road to getting on The Tonight Show, how he created just a little bit of chaos when he was on, and why he was eventually told he could keep coming back, but never when Johnny Carson hosted. You can read an excerpt from the transcript or listen to the full episode below. Tune in to Good One every Thursday on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Overcast, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Good One

Subscribe on:

How did you find your voice, your persona?

Well, April 19th, 1977, to be exact, I went to a comedy club called Yuk Yuk’s in Toronto. It was the first time I saw stand-up comedy live. They said, “At midnight on Mondays, amateurs can get up.” The people I was sitting with said, “You should get up.” And I went, “Okay, okay.” I have mental-health issues, but I always say yes and don’t think of ramifications. So I showed up thinking the joke is going to be they’re going to go, “Ladies and gentlemen, Howie Mandel,” and then I’m going to walk out and it’s going to be me — like I’m not a comedian, and they don’t know I’m not a comedian — and that’s the joke. That’s the extent. So, I was introduced, and I walk out. There’s a smattering of applause, and then that applause dies down. Nobody knows who the hell I am, and I barely know who the hell I am, and I’m standing there blinded by the spotlight. You could see the front row, and there’s just people who I don’t know looking up at me like, Okay, funny boy, you were introduced. That realization became terror and I realized, What the fuck did I just do?

Just like when a mom finds her child under a car and has that ability, that energy that goes through, I just started going, I’ve got to come up with things. I’m actually just really, legitimately, authentically panicking, and I’m going, “Okay, all right, all right, all right, okay, okay.” The audience started giggling at my discomfort, and I didn’t really understand because I was so self-conscious. So I start going, “What? What? No, really, What?” I started saying things like, “Oh, come on, don’t laugh. It’s throwing me off.”

I suffer from OCD and have my whole life, and I remember being uncomfortable, putting one of my hands in my pocket, and thinking, Oh shit, I got a rubber glove that I carry because I don’t want to touch things in a public restroom. So I took the rubber glove out, just needing to do something. I pull it over my head and pull it past my nose. I never had done that before. I started breathing, and the fingers are going up and down. I can hear the audience is roaring. So I just started inflating it with my nose, and it blows up and pops off my head, and they go into spontaneous applause. I go, “Good-night.” And [co-founder of Yuk Yuk’s] Mark Breslin is there and he goes, “That was amazing. Come back tomorrow.” I go, “For what?” He goes, “You do it again.” And I go, “Do what again?” And he goes, “Do what you did.” I didn’t do anything, but I started coming back and showing up at that place.

You continued in this style for years to come, including on TV sets, like the HBO Young Comedians special. From there you got a lot of TV work, you played theaters. What did The Tonight Show think?

If you didn’t do anything else with your career, the one thing that you would want to do is to be on Johnny Carson. I had everything — everything but The Tonight Show. Every week, Jim McCauley, who was the casting person for comedy on The Tonight Show, would be at the Comedy Store or the Improv. Every time he saw me, he’d go, “Not only am I not going to book you, you’re never going to be on the show.” He wasn’t being mean. He just said, “What you do is not what Johnny likes. We like monologists. We like people who tell jokes, people who have a point of view. You’re just this silly little man who just runs around.”

Did you try to adapt your style?

I’ve always tried, but I’m going to be totally honest with you: It always bothered me. It was a very dark time at the Comedy Store. Everybody was fighting and clawing to try to make their way to the top. And in their view, I didn’t put a lot of time and work into it, so I didn’t deserve the success that fellow comics saw me getting. I was getting killed for using a lot of silly props. When I walked into a store, if there was a little toy or a bag of candy, whatever there was, I would just buy it, without an idea, just hoping I would get an idea. I don’t think prop comics even today get the props they deserve and the respect. It’s just as hard to come up with a prop or look at a prop and find something to say alongside it. It’s all subjective, but I was getting killed. Even when Letterman was at his height, I can’t tell you how many times I was, to my chagrin, in the “Top Ten.” It was always “and then we’re going to force him to go to Howie Mandel concert.” And that killed me. Killed me. I just was so embarrassed, so hurt, so destroyed.

It’s interesting because watching your old set and specials, it feels like there are multiple time periods in comedy where what you were doing would’ve seemed like the cutting edge, in how free flowing you were with the audience. It’s like if you came up in the ’50s, you’d be seen as interesting because of how you improvised. But the 1980s was the exact time where what comedians wanted was these super-polished acts, where you were all about connecting to the audience.

You’re absolutely right, except the dichotomy you’re talking about was between my peers versus the audience. There’s a huge dichotomy, because I went on that one Young Comedians special and I’m selling 100,000 tickets at the same time, but nobody at the Comedy Store likes what I’m doing. I’m the joke. I don’t deserve it. I don’t write. So I was torn between, Am I good or are people wrong? Is this audience wrong?

One of the big, momentous moments in my career was when I was asked to play Radio City Music Hall in the early ’80s. They put tickets on sale and it sold out in hours. They said, “You want to do a second show?” I said, “Well, I don’t want to stay away too long from home, so I’ll do a second show the same night.” That sold out, so now you’re talking about 14,000 people in one night in New York City. Night of, in between shows, my wife and I look out from the dressing room onto Seventh Avenue, and there’s 7,000 people walking out of the first show and 7,000 people making their way into the venue for the second show. You look out on Seventh Avenue, and there’s 14,000 people in the biggest quagmire I’ve ever seen on a city street. They’ve got stanchions in the street and cops, and traffic is fucked up. My wife says, “What are you thinking? This is all for you.” I said, “Well, I’ll be honest, this is what I’m thinking: This city is probably the biggest city in America. There are 10 million people here. What I really see is that 9,986,000 people don’t give a shit. Those odds aren’t really good.” I was chasing The Tonight Show. I was selling out Radio City; it didn’t matter. I had all these people coming; it didn’t matter. It didn’t matter that I was getting notoriety and I was on a network show. I needed to do The Tonight Show.

More From This Series

- How to Turn a Comedy Podcast Into a Comedy Documentary

- This Is Judd

- Ramy Youssef on the First Israel-Palestine Joke He Wrote After 10/7