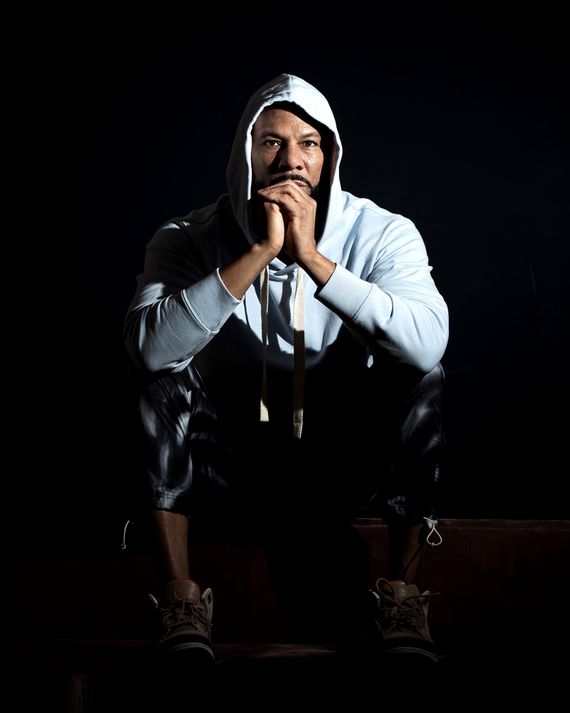

Survey most hip-hop heads and they’d agree Common hit legend status more than a decade ago. He’s an icon of “conscious hip-hop” — the long misunderstood, often oversimplified subgenre that’s become shorthand for a willingness to lyrically speak to Black people’s fight for basic human rights, even the right to self-love — and as both a soloist and a collaborator with acts like Talib Kweli, Yasiin Bey (f.k.a. Mos Def), Erykah Badu, and J Dilla, he released bona fide rap classics with 1994’s Resurrection and 2000’s Like Water for Chocolate. The former wrote hip-hop a fairy tale, “I Used to Love H.E.R.” — a song lamenting hip-hop’s direction toward commercialized gangsta rap and away from empowering, Afrocentric ideals — and when Ice Cube ridiculed him for it on “Westside Slaughterhouse,” Common released the blistering “The Bitch in Yoo” as his response, resulting in a Hall of Fame diss track. Then, in the mid-2000s, he signed with Kanye West’s G.O.O.D. Music and took his brand of thoughtful rap mainstream, earning a gold plaque for his 2005 masterpiece, Be.

The music has yet to stop, but now, at age 48, Common has carved himself a niche outside of hip-hop as its ambassador, an assertive yet nonthreatening voice that companies can rely on so as to appear hip and on the right side of history. In recent years, his fatherly, Chicago-inflected voice has been used in commercials for Microsoft and to introduce the rosters at the NBA All-Star Game in his hometown. Historically white artistic institutions and politicians alike in need of Black approval have leaned on him: He and John Legend’s song “Glory,” from Ava DuVernay’s Selma, won a Golden Globe and an Oscar; he earned another Oscar nomination for his Diane Warren collab, “Stand Up for Something,” from the Chadwick Boseman–starring Marshall; former president Barack Obama invited him to the White House for a poetry reading. He’s made the same inroads in Hollywood, appearing in strong ensembles like American Gangster, opposite Queen Latifah in Just Wright, and fighting Keanu Reeves to the death in John Wick: Chapter 2.

Some critics and skeptics find his calm, accessible persona corny and predictable; others find it dependably familiar, especially the music. His latest, the taut, independently released October EP A Beautiful Revolution (Pt 1), produced by longtime collaborator Karriem Riggins, covers all his bases: He questions the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, calls b.s. on justice reform, demands the close of the financial inequality gap, and conjures prescient images of neighborhoods being stormed by the National Guard. As much as he looks to be an accessible, omnipresent bridge to make people consider new perspectives, he’s also willing to speak his own mind — and has lots to say. Over a December call, Common makes sense of his reputation.

Your career and your place in society is really interesting. During the Obama administration, you were going to perform at the White House, and Fox News tried to vilify you for making a song about Assata Shakur. [Editor’s note: Longtime Daily Show host Jon Stewart notably defended Common’s stance during a visit to Bill O’Reilly’s show.] What is it like to have made songs like that for so long but to now see Black Lives Matter on a basketball court and to see companies tripping over themselves to issue BLM statements?

I always feel like, man, people get there when they get there. Let’s face it: Some companies are doing it to save their faces as dollars go. But some are sincere, and I really do believe that some people within those companies are like, “We gotta do something.” I used to always sit there and think, How are these companies making all this money and feeling no type of compassion toward the people that are supporting them? I just don’t get the concept. If I’m riding by in a nice-ass car, life is good for me, and I see hungry [people, how are you] not looking out for them? To me, metaphorically, that’s what companies are doing. People are now smarter. We’ve been through enough experiences of companies just hopping on bandwagons. You can see through advertisements about what the intention is. A lot of people don’t fall for it as much. And I think the people in the companies that have already been on it, they’re showing up, and it’s showing. I have no problem if you’re saying, “We’re gonna honor Black lives and say what needs to be said,” but I also want action with that too. It’s certain things I’m late to the table on. I wasn’t in criminal-justice reform 20 years ago; I didn’t even know how to address it. I knew it was systemic, but I wasn’t really able to break it down to how and why.

I’m saying that to say: I meet people where they are; I’ll meet the companies where they are. Okay, you want to be a part of this? Come on, let’s do some real work. That’s the most important thing for me at this point. Even if you’re doing it to be like, “We want our company name to be seen” — if it’s doing real work and changing people’s lives, then I can still rock with that. But along with you saying it and showing it in your commercials, I just want to see some decisions being made. If you’re going to say Black lives matter, then we need to see some Black people in leadership within those companies and at the table expressing how some Black people feel. And it ain’t just gotta be only a Black thing. It’s Latino people being overlooked, women that have been overlooked. It’s going to be steps, but equality is going to have to happen across the board.

You’re a very respected person: A lot of people trust you, you make music that makes people feel good about themselves, and you speak up for what’s right. But among many pro-Black activists, there’s legitimate distrust for corporations, distrust for government, distrust for technology. Do you bring any of that skepticism into your partnerships? How do you decide which companies are worthy of your co-sign versus who can take advantage of it?

I started off being like, Man, I ain’t messing with these companies. I remember one of my first things that was brought to me — this was during the times of Like Water for Chocolate or Electric Circus — was a big corporation deal with Coca-Cola. I was like, Hell no [laughs]. My whole team, my mother, called me, like, “This is the biggest deal you’ve ever had.” My mother was like, “This is going to pay your daughter’s tuition.” My management is like, “How could you pass that up when we’ve worked this hard?” I just felt like it wasn’t representing what I wanted to represent. So they ended up coming back, and I said, “Yo, this is what I’ll do. If you let me have creative control over this, and I can have who I want to direct it, [I’ll do it].” We had Chris Robinson [direct]. I had James Poyser and the Roots produce it. I was rapping about what real and fake is. Within the commercial, I was kinda saying, “You ain’t going to get me.”

That was the beginning of me understanding that the times that I partner with companies will have to be something where the agenda is bigger than me and them. You’re not gonna see me endorsing a company [where] I don’t believe real work is going to be done. I have a great partnership with Microsoft; some of those things that they’ve done for my foundation and kids in Chicago are things that are important to me. When I sit down at the table, it’s just like I do with a politician. I use my discernment and my own wisdom to say, Is this person sincere? Do these plans strike me with sincerity? And if they don’t feel right, I don’t do it. I’ve been offered some opportunities, but [I don’t do it] if it’s not in alignment with what the vision is and what my purpose is: to inspire and to uplift and to stand up for the people. To be honest, most companies that come to me at this point, they’re like, “We need to do something within the community, so what’s up?” My philosophy on that is: I can create some real change in people’s lives by guiding some of the people who run these companies and have the power within them to know what they need to do.

I’ll give you another good example: After John Legend [and I] won the Oscar for “Glory,” different people were reaching out to me. Howard Schultz, who was the CEO of Starbucks, reached out before the Oscars, actually. I just got to know him. He had been having these sessions in Starbucks [between] community leaders and the police. This was right after Michael Brown got killed. He said he was so moved to do something. He and I sat down with no agenda, just to talk. We eventually started building more. He was like, “What kind of things can we do?” It wasn’t, like, him saying, “Yo, can you do a song for us?” We ended up doing something in Chicago, the 100,000 Opportunities Initiative. He called all these other corporations, and they all came in and we had a whole day for young people from the hood. I was seeing people from the South Side of Chicago, West Side, coming up getting job training, filling out applications, getting that guidance. They had people to help them with clothing they needed for job interviews. A year and a half later, I’m on set filming for The Chi, and a young lady walked up to me, like, “Yo, Common, I’m coming home from the job that you got me.” Tears came from my eyes ’cause I was like, Yo, this really works.

It don’t always pan out. When I did the commercial with Coca-Cola, it wasn’t like they did so much in the community. Maybe they were, but I didn’t know what they did. But I felt like I could get a message across on that one. But now I’ve grown to know if it ain’t no social or activist component to it, you won’t see me doing an advertisement or partnership with a big corporation.

I was also not into politics at all. I looked at politics like, These dudes don’t care about us. But I started to realize that, as much as I care about my people, and I keep saying it and I’m speaking on it, these politicians are affecting my people. The attorney general in Kentucky didn’t put the police officer who killed Breonna Taylor on trial — that’s an elected official. The juxtaposition of that is the people [among] Minnesota’s elected officials said, “Yo, this dude is going to be on trial. This is unjust.” Those elected officials are the ones making decisions. The same people that say “Now marijuana is legal” can also say “These people who have been locked up for selling marijuana for half their lives deserve to be out.” Just like this new DA [George Gascón] in California who is removing cash bail — I’ve been part of getting a bill passed in California, called SB 394, where juveniles no longer can be sentenced to life without parole. And I sat down with politicians — they came to concerts that I did in prison and sat down with people who were incarcerated. I gotta be involved in politics because this is actually affecting our lives. Doing that work is one of the things that I’m most proud about ever in my life.

These days, you’re seen as a hip-hop ambassador — you use hip-hop as a bridge to speak to different groups of people. I think that there’s a perception of you as “safe,” at least as safe as a Black man can be. But I can listen to old Common songs like “Heidi Hoe” and see you weren’t always that way. What do you make of your image?

I do believe, in some instances, I’m seen as safe. Overall, a lot of the people that you’re saying — whether it’s a corporation or some of the politicians — they ain’t gonna meet up with me if they think I’m going to get caught up in something, ’cause that’s going to make them look bad. What it makes me feel is that they recognize the integrity that I bring, and they recognize the honesty, too. I wouldn’t shy away from it. If somebody [says], “You did a song called ‘Heidi Hoe,’” or “You did ‘The Bitch in Yoo,’” “You used to fight during this time,” [I can say], “But, hey, I see you had something on your record before.” I feel like I represent the everyday person that understands that we are human beings. I represent the person that is working daily to be better, the person that actually can be as honest with themselves and honest with others as possible. I also represent somebody who cares for not only himself and his loved ones but cares for his community and overall cares for people. I care for people, and I think they feel that. That part also ends up feeling safe.

Because, ultimately, I’m not anti-white — I’m anti-hatred, I’m anti-ignorance, anti oppressing people. I got love for white folks, brown folks, Asian folks; I got love for people. The safeness comes with part of my history and the integrity of what I do and who I am. Even if I do make a mistake, I’mma acknowledge it and work to get better. We live in a time where you can get canceled for certain mistakes. I would have to just acknowledge my work to be better. To be honest, a lot of my beliefs and philosophies and spirituality usurps and overrides some of the things that they expect and want. I just bring my honest and true self to the table. And if that ends up being called “safe,” cool. If it ends up being called a “rebel,” great. If it ends up being called “a man of the people,” that’s what it is. But at the end of the day, I know my intention of love and creating a better place. And that’s what they are drawn to more than anything.

Does it ever feel restrictive to be seen that way? Like you can’t show certain sides of yourself? I think back to the August Greene album where you said, “I’m supposed to go high when they go low / I forget the big picture and, snap, like a photo.”

A lot of what is seen is about the socially conscious aspects of me. That’s what I’m asked to talk about in the interview, and that’s who I am. If you get in a conversation with me, I love to joke and talk shit, but I will get into something that is talking about life, or I’ll be listening to you, wanting to know how we can get better. So I don’t think I’m being wrongly accused of being someone that’s so aware and that functions in socially conscious spaces, but I also like to have fun, and that’s one of the things that I think gets overlooked. And I’m a South Side dude, so it ain’t like I’m gonna sit here and be a punk in a situation. I talk about love a lot, but I ain’t talking about love where you just fold over and be like, Oh, smack me. And I’m just going to take it. I believe in Black Panther love, too. That was revolutionary love. They protected our families and their communities, and they also were feeding the children. I believe in a Malcolm X love, speaking the truth. But I also believe in the Marianne Williamson self-growth love of self. And, truly, I believe in the way of God’s love. I have no problem being stereotyped in that way. But people don’t talk about the raw sides of some of the people that we looked up to as leaders.

Over the past eight years, we’ve seen the Obama administration end and the Trump administration begin and end. How have both of those presidencies changed how you view the country and the world and how you choose to use your platform?

When Obama was president, I felt like it was one of the first times I was a part of America. The possibility of us breaking through the system was there because Obama was the president, and it’s a Black woman as the First Lady. We have a long way to go, but we accomplished something. Seeing him made me know that we could actually change the system. This is our country. Before, I was in that space of, I ain’t a part of this country overall. But, man, our ancestors earned it. They were enslaved and built it. We’ve created so many things as Black people in America. So I started to see the potential of what it means to be a Black American when Obama was in office. I also started to understand that because he couldn’t get certain things done, it’s politics. It ain’t just the president that can make the decisions; we need other aspects of the government to be aligned to start making things happen. That got me more involved in politics. It gave me an unprecedented hope: Our children saw a Black man as president. I’m in the White House, and D-Nice is playing Mobb Deep and A Tribe Called Quest. This is different, man. The world can change. We are changing.

With President Trump — ah, why did I say that? I never call him President Trump. When Donald Trump got into office, what I noticed was that it was more people than I knew that felt hatred seeing Black and brown people have opportunities they would take away from them. It was awakening, but it also made me go deeper into, What can I do? My mother said this to me the other day, and it was true: “I didn’t know as much as I do about politics now ever in my life, and it’s because Donald Trump was in office.” What he did was make us say, We need to know all the details so we can change this situation. I campaigned and canvassed in ways that I did because Donald Trump had been in the office. His presidency made me become more educated, more diligent, and more passionate about changing the political structure and electing officials who represent the people.

What direction do you think Black leadership should be going in right now? What should they have learned?

Black leadership has to have learned that the more we are in tune with the people we represent, the more we can truly reflect them. That means going to the grittiest of places and being able to lift and take that in. Then making sure that things are aligned to be effective to those communities and places that you just visited — staying engaged with those communities and having people there to represent you when you’re not around. Empowering those communities would mean a lot too. One of the biggest things I learned about leadership is that the best leaders know how to listen and translate that into action.

That’s what I think Black leaders can get from this. And the people who have done the work to help Joe Biden and Kamala Harris get elected — we got to hold them accountable. The work that a lot of the Black church leaders did to support, any work I’ve done to support, I gotta hold them accountable and get what the community needs, get that reflected in action.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.