Thirty-five hours before he was murdered, 18-year-old Jayquan McKenley was sitting on a yellow beanbag chair in a teacher’s office at the Children’s Village, a residential facility for at-risk youth, including juvenile offenders, tucked away in the woods of Westchester County. The campus includes a school, ball fields, and dormitories with beds for 137 students. On Fridays at 3 p.m., McKenley attended a voluntary after-school mentorship program called Bravehearts run by Robert Ramaseur, a 26-year-old from East Harlem who had lived at Children’s Village as a teen. Ramaseur would lead the Bravehearts through exercises like “Monster in the Basement,” in which students would try to identify suppressed traumas, such as “death, substance abuse, seeing things that you shouldn’t have seen when you were younger.” A dry-erase board featured a little cyclops at the bottom of a staircase, flexing its arms and looking a bit like the creature from Monsters, Inc.

A charismatic emerging rapper from the Bronx and a basketball talent — he averaged 17.9 points a game and was selected for the All-Conference Team — McKenley was the resident celebrity of Children’s Village. On campus, he assumed a leadership role, participating enthusiastically, showing up to class on time, making the younger kids who idolized him feel included. He also had a melancholic side. In one Bravehearts session, students were asked to name something missing from the juvenile-justice system through which they were passing. “Unconditional love,” McKenley said.

That Friday, February 4, 2022, the Bravehearts were studying the Mississippi Freedom Rides of the early 1960s. Ramaseur was preparing the kids for a trip down South that summer to mark the anniversary of the protests. Ramaseur had been out on sick leave, and when McKenley saw him, he ran up and dapped him hello. McKenley told him his court-ordered term at Children’s Village would be up in a few weeks, but he wanted to stay involved with the program. Come summer, he planned to join the Freedom Ride.

McKenley’s agreement allowed him to head back to the Bronx on weekends, where he was staying with his girlfriend, Jamayra Ingramm, and her mother. McKenley’s father, Perry Williams, lived in North Carolina with his wife and their two daughters; his mother, Naomi McKenley, had been living in temporary housing after a fire in her apartment. That Friday night, at Ingramm’s, he was working through some feelings he didn’t want to talk about face-to-face. He went into the bathroom and texted Ingramm from there. It was after 2 a.m. The couple had been fighting. He questioned his parents’ love for him, why his mother had not just aborted him, what awaited him in the afterlife. “What is after death,” he texted. “Why should I live not even knowin where ima goo.” She wrote, “i guess, Jayquan, you brushin it all on me like everything is really my fault.” He pushed on: “Like am I goin to hell for the shit I did.”

McKenley’s rap name was C-HII WVTTZ, and he was a part of the scene surrounding Bronx drill, a new variant of the hip-hop genre that had emerged in Chicago in the 2010s before migrating to the U.K. and Brooklyn. The Bronx sound is defined by high-tempo rapping, mostly about real-life violence, set to sped-up melodic samples and scuzzy, sliding 808 bass lines. McKenley wasn’t represented by a label, though, according to Ingramm, he was taking meetings in Miami and Los Angeles.

WVTTZ, pronounced “Watts,” was a reference to the L.A. neighborhood. C-HII, pronounced “C-high,” signified McKenley’s allegiance to the Crips. Specifically, he was associated with a smaller Bronx gang known as DOA 700, or Sevside, whose territory covers the area around East 187th Street in Bronx’s Belmont neighborhood. DOA’s rivals, or “opps,” are the Young Gunnaz, or YGz, whose territory includes the River Park Towers complex overlooking the Harlem River. The rival groups each include a number of drill rappers.

In June 2021, McKenley allegedly fired a gun into a vehicle, for which he was charged with reckless endangerment and criminal possession of a firearm. Nobody was hurt. He posted bail after spending six days on Rikers Island but was subsequently sentenced to a term in Children’s Village — a placement a rival rapper once mocked during a conversation they were having on Instagram Live — for violating his probation. (His father said he’d been involved in a robbery as a minor.)

On Saturday, February 5, McKenley traveled to an Airbnb in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood to shoot a music video for a new song, “WVTTZ.” The spot was off Lewis Avenue in a four-story walk-up several blocks north of the popular bakery and restaurant Saraghina. In the video, McKenley and his crew are jammed into the apartment, pointing finger guns at the camera and playing Nets versus Blazers on an Xbox.

McKenley begins the song, “DOA, DOA, DOA. DOA, DOA, DOA,” then adds, tauntingly, “Rah Rah. Rah Rah.” “Rah Rah” referred to Rah Gz — Ramon Gil-Medrano — a 16-year-old alleged YGz affiliate who had been murdered in the back of a cab the previous summer and whom McKenley had mocked in songs before. In the first verse, McKenley raps, “Still outside nigga totin’ the Colt / DOA be the niggas I came with / We see a Gz we leavin’ him faceless / Locked up, still fighting these cases.” In the second verse, he seems to refer specifically to Rah Gz’s death. “Got caught in a cab and that little nigga died / Stupid nigga got his head fried.”

Around 2 a.m., McKenley left the Airbnb to record a scene for the video. According to the police, two individuals shot him from a car, one from the front seat, another from the back, hitting him twice in the chest. He was driven to nearby Woodhull Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at around 2:30 a.m.

Before his death, McKenley was not a household name. But set against the backdrop of the city’s rolling crime surge, his murder triggered an unusually public chain of events. Drill rap has been intertwined with gang affiliation since its inception, but the volume of recent casualties was unusual. Less than a week before McKenley’s death, Tdott Woo, a 22-year-old drill rapper from Brooklyn, had been murdered in Canarsie, and about a week before that, a rapper from a rival crew was shot in his leg and back in Prospect–Lefferts Gardens. Around this time, Hot 97’s DJ Drewski — an early champion of the genre — announced he would stop playing drill diss tracks on the air. “If you make drill music,” he wrote on Instagram, “there are a lot of drill songs without dissing your opps or smoking your opps!”

Eric Adams, then early in his mayoral tenure, seemed distraught after McKenley’s death, and on February 10 he delivered a tearful 13-minute speech calling on his administration to save future Jayquans by investing in housing and education and jobs. More controversially, he critiqued drill itself, describing a “scene that involves using music as a challenge on social-media posts — posts that bled out into violent real-world confrontations.” In a press conference the next day, he free-associated, wondering whether some drill-related posts could be censored online, the way Donald Trump had been removed from Twitter after inciting the Capitol riot.

That wound up turbocharging the news cycle, as Adams was accused of being a moralist and a concern troll, a contemporary version of the stuffy pundits who tut-tutted N.W.A and other gangsta rappers in the ’90s. Fivio Foreign, who has succeeded the late Pop Smoke as the king of New York drill, tweeted at the mayor, “it’s deff not the music that’s cause’n or contribute’n to the violence.” (Fivio was close with Tdott Woo, the designated dancer of his crew.) Within days, The Daily Show’s Trevor Noah would devote a segment to drill, featuring a photo of McKenley grinning in his Children’s Village Hawks basketball jersey. Noah was ambivalent, defending artistic license while critiquing drill rappers for their poor taste. “Why do you gotta make songs dissing a dead rival?” he riffed. “It’s not like God’s up in heaven like, ‘We were gonna let you in, but Lil Tre bodied you up so hard.’ ”

A decades-old debate resurfaced about whether certain hip-hop lyrics glorify or merely reflect violence. A mayoral crackdown on drill — functionally impossible anyway, unless Adams could pressure YouTube or Columbia Records to act for him — never materialized, nor has an official mandate to the cops, who, in any case, had been investigating drill rappers’ gang ties since the de Blasio administration. In mid-February, Adams smoothed things over with Fivio and a number of other drill artists in a late-night meeting at City Hall. By the summer, the mayor was having dinner with Rowdy Rebel, a Brooklyn drill pioneer. “I exercise to drill music,” Adams told me recently. “I enjoy drill music.”

New York drill, as told by …

19 artists who define the scene.

.

The tragedy of Jayquan McKenley.

The sound itself.

The essential tracks.

Lawyers and lawmakers.

In general, the discourse around drill seemed stuck, unable to move beyond the binary of “art or provocation?” But Adams, despite his distracted approach to finding solutions, hit closer to the heart of the matter by citing the role of social media. Drill, like any other ecosystem dominated by teenagers, plays by the rules of online engagement. Bronx drill in particular has a callout ethos in which rivals publicly insult one another, often on Instagram, with much of the back-and-forth not set to music at all.

Even to drill’s defenders, it seemed clear that social media had sped up a cycle of retaliatory shootings; the Bronx’s pandemic-era spike in gun violence persisted through 2021 and into 2022, even as it abated in other boroughs. Countless factors were at play: access to firearms, peer pressure, institutional failures at every level. “What social media did is kind of made it fashionable for these kids to be that disrespectful with one another,” said the rapper Maino, who brokered the meeting at City Hall. “It gives them a vehicle to do that in real time and gives the fans the opportunity to watch it in real time.”

The day after McKenley’s death, as rain drizzled in the Bronx, Ingramm streamed herself on Instagram Live from the passenger seat of a car. Braces showing, she lit a joint, cued up C-HII’s music on her phone, and started wading through a stream of incoming comments, some of which involved rumors about who might have killed or betrayed her boyfriend:

rah rah saying he getting beat up in heaven by Chii

let me know if u want his clothes from cv

Doa down bad

Yo heard dat man kay flock set him up

Pulling up to a sidewalk vigil for McKenley, Ingramm told off the disrespectful commenters but kept the stream live while she fussed with his candles and a poster-board tribute.

When he heard the news, rival rapper Yus Gz hopped on Instagram too. He shared a photo of McKenley overlaid with the text “And Another #1 bites the dust 🤣🤣.”

Within hours, someone compiled this insult and others in a YouTube video that would eventually get about 60,000 views: “Sha Ek, Lee Drilly, Yus Gz and Opps Dissing Chi Wvttz After Getting Killed!!!”

Until he was 10, McKenley lived with his mom in the Bronx. His father, who spent part of his son’s youth in prison, told me he was once in a Blood-affiliated crew but moved down South in his late 20s to escape gang life. In 2014, he brought McKenley to Henderson, North Carolina, to join him. Williams told me his intention was to keep his son from repeating his mistakes. After being suspended for an incident with a razor, he said, McKenley got his act together and made A’s in school while fishing, shooting hoops, and rapping on the side. In 2018, McKenley’s mother wanted her son at home, so he went back north. (Naomi McKenley did not respond to interview requests.) Ingramm has claimed online that McKenley wasn’t happy in North Carolina and that he once tried to drive to New York on a dirt bike until its tire popped on I-95.

In January 2021, while attending high school in the Bronx, McKenley released his first music video on YouTube, for a song called “Sanctioned,” in which he raps over a spare piano riff. The video — he and his friends bouncing around an apartment with a Christmas wreath hanging on the wall — features some of Bronx drill’s rising stars, including Dougie B and Kay Flock, who within a year would be cutting songs with Fivio Foreign and Cardi B.

That spring, McKenley joined Dougie B and Camrin Williams, who performs under the name C Blu, in a Bronx studio to record a song called “Geeked.” Camrin told me McKenley had an incredible work ethic. “He liked to be in the studio a lot,” he said. “He liked to make sure he had a long list of songs done, not just one or two. He was prepared.” That day, Camrin said, McKenley had come with his lyrics written out beforehand, ready to go. He put on a beat and told them, “I need y’all to get on this song and make it go viral.”

There are many more teenage drill artists in New York City equipped with stage names and iPhones than there are with record deals. Lifting rudimentary beats off YouTube and releasing snippets of a song on social media are enough to declare yourself a drill rapper — or enough for the tabloids to deem you one if you make the news for something tragic. McKenley was somewhere in the middle: known mostly to online devotees but possessing more talent than many of his peers. Management companies began posting in his Instagram comments, telling him they could make him famous.

In late October, he was sent to Children’s Village, stalling his hip-hop career. There was a recording studio on campus, and McKenley could try to shoot videos on home visits, but it seemed he mostly channeled his drive into classwork and basketball during his time in the program. “He had a specific goal here that was separate from the life that he had at that time,” said Anthony Colon, his basketball coach. “Okay, what can I make of this while I’m here? He didn’t like to waste time a lot. He wasn’t a kid that was just kind of sitting around.”

Colon told me a bit about his athlete’s quirks: He craved Twizzlers and loved ranch dressing and wore his warm-up sweats tucked into his socks — an affectation he had picked up down South. He told me McKenley’s energy on the floor was infectious, that he took lots of bad shots but thrived in big moments.

McKenley grew close with a teammate from the Bronx named Miguel Pena, who jokingly insisted that he was the more talented of the two. But he conceded that McKenley, the point guard, was the teammate the other players looked to first. “I ain’t gonna lie, I was more like the co-captain,” Pena said. “He naturally had that leadership ability in him.”

Pena was a day student and, unlike McKenley, was allowed to have his phone on campus. During practices, Pena would lend it to him so he could text Ingramm. McKenley told him he drilled because it was popular, but, Pena said, “he wanted to change it up, make love-type music like R&B.” After he made it big, or if he didn’t end up making it at all, he wanted to start a family and have a son.

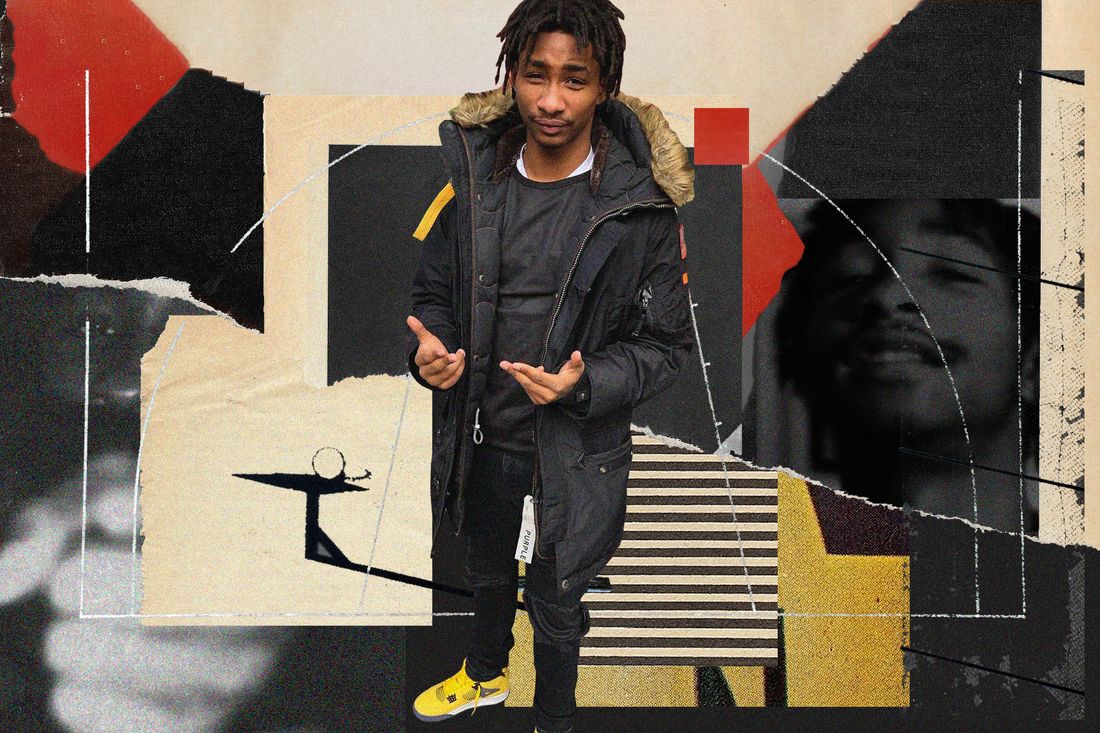

By all appearances, Kay Flock, born Kevin Perez, has the career McKenley wanted for himself. A year ago, the two of them were in photos on Instagram together, showing off their outfits. Now Kay Flock has a deal with Capitol Records.

Kay Flock is also tied up in the feud between DOA and the YGz. There are numerous videos of him on YouTube in which he records himself marching to the River Park Towers or other rivals’ turf and begging his opps to come out and confront him. The term of art for this is “spinning” a rival’s block.

The crews to which Bronx drill artists claim loyalty tend not to be sophisticated criminal enterprises accused of trafficking guns or narcotics. They fight over real territory but are mostly preoccupied with gaining clout on social media. The incentive to respond to each insult is heightened by its publicity. Things can escalate until, as Maino puts it, the disrespect reaches “a level you can’t swallow.” As McKenley rapped in “Geeked”: “We see a notification, my niggas, they ridin’ / My niggas, they ready to spin.”

Police argue that this dynamic in particular directly contributes to bloodshed in the form of “on sight” shootings, in which rivals target their opps as soon as they see them. “I have never seen so many investigations where gunfire is met by opposing gunfire, by multiple guns, by both teams,” says Jason Savino, commanding officer of the NYPD’s Gun Violence Suppression Division, which oversees major gang cases. (There have been 324 shooting victims in the Bronx as of August 7 of this year, compared to 145 through the same period in 2019.)

In the course of investigating such shootings, the cops wind up monitoring drill rappers the same way fans do: by bingeing online content. I spoke with homicide detectives as well as higher-ups who study not just the songs themselves but also the cottage industry of mini-documentaries and reaction videos that flourishes on Reddit, YouTube, and Instagram, giving them deep familiarity with even the most obscure artists.

In the spring of 2022, following an investigation by Savino’s division, the Bronx district attorney Darcel Clark indicted 23 alleged members of RPT, a YGz-affiliated group from the River Park Towers. She said several drill rappers in the group had bragged about their crimes in their songs; the most serious allegations were attempted murder and conspiracy to commit murder, though the livestreamed beating of a pigeon generated the most media attention. In a press conference, Clark urged rappers to stop “using music to encourage shootings and use it to better the community.”

Although the investigations began before Adams took office, their timing added to a suspicion that law enforcement was scapegoating rappers. The NYPD already has a “hip-hop surveillance unit,” officially the Enterprise Operations Unit, which effectively muscles promoters into taking certain artists off concert bills in New York by arguing that the threat of gun violence at the shows is too high to let them perform. Bobby Shmurda spent several years in prison for crimes that he also rapped about, though prosecutors didn’t explicitly mention his songs in the indictment. In May, the State Senate passed a bill, supported by Jay-Z, Meek Mill, and other stars, designed to limit the use of lyrics at trial. (It is still before the State Assembly.)

Several weeks ago, the three detectives who led the investigation into RPT — Michael DelGardo, Patricann Caputo, and Brandon Ravelo — met me in an unmarked NYPD building in the North Bronx. I had asked them to show me how they connected drill rap to gang violence. DelGardo picked an example from a related case, an investigation of a gang called the G-Side/Drillys. In July 2020, he said, a 24-year-old named James Rivera, a.k.a. Lil Loc, was leaving his girlfriend’s home on the corner of 209th Street and Decatur Avenue in the Bronx when he ran into members of the Drillys gang. DelGardo says Loc was a Crip and that e Drillys are Bloods. A confrontation broke out and Loc was shot, dropping a knife, which DelGardo says one of the gang members picked up and used to try to stab him. Loc died at the scene.

In the course of the investigation into the Drilly gang, the detectives began to take notice of a rapper named Lee Drilly, real name Ali Doby, who had mentioned Lil Loc in a song called “Final Destination.” “He names about 25 individuals who were killed, assaulted,” DelGardo said, and includes the line “Little Loc got put in a casket, spinned with a knife, that nigga got blasted.” In another song, “Bet,” Drilly mentions the knife again. The detail about the dropped knife, caught on police surveillance video, would not have been public knowledge. DelGardo and his partners took another look at the tape and identified Drilly as an individual who picked up the knife and attempted to stab Loc. He was charged with conspiracy to commit murder in the second degree.

DelGardo and his team are aware that mining hip-hop lyrics is a bad look for police. They repeatedly stressed that they use the music only as an investigative tool. “There is no district attorney in New York, probably the country, that would allow a prosecution off of a song,” he said. “Everything we do is corroborated by further evidence.” Ravelo added, “Some people think we just watch videos.” Doby’s attorney, Phillip Hamilton, says evidence will show that his client “did not concoct a plan to harm anyone” and did not try to stab Loc. Drill lyrics, he argues, are being taken too literally. “Anita Baker sings about love and all these intimate emotions,” he says, “but for all I know, Anita Baker could be a sociopath.”

When I spoke with Mayor Adams, he insisted he had no problem with drill itself but doubled down on critiquing inflammatory lyrics. “When you looked at the music of the early rappers, what you saw was that they were rapping about the realities of their lives. What you’re seeing here, which is extremely dangerous in some of the drill music, you are now calling out others to retaliate,” he said. “Black music has always come under scrutiny — I don’t care if it was jazz, gospel, the blues. And then during the mid-’80s, early ’90s, hip-hop artists, they had the hip-hop police.” His own scrutiny of the music isn’t “here we go again,” he argued. “This is something totally different.”

Adams accused the social-media companies of exploiting violent content for profit. “They know exactly what they’re doing. They know what promotes clicks,” he said. “So what we’re saying is use your algorithm, your artificial intelligence, to identify key words, key actions, displaying of guns — all of this is possible — and start being socially responsible.” Adams said he’s in conversation with all the major platforms and meetings with them are forthcoming. When I asked whom he’d be sitting down with, he replied, “The ones we believe we’re making traction with, we don’t want to release names and blow it up until we are able to seal a deal.”

Police have not yet arrested anyone in connection with McKenley’s death. Savino said McKenley wasn’t even on his department’s radar until he was murdered. “We found him because RPT was posting so much thereafter,” Savino told me. The investigation is still open.

Kay Flock, in the meantime, is awaiting trial for murder on Rikers Island, following a December 2021 shooting in Harlem. He has pleaded not guilty and his lawyer has suggested he acted in self-defense. In the music video for “Shake It,” Kay Flock’s blockbuster collaboration with Cardi B, he is represented onscreen by a shot of a prison call on an iPhone. (“Bronx Rapper Kay Flock Arrested for Murder After FaceTiming on the Opps Block,” a video analyzing the shooting, has more than 700,000 views on YouTube; “Shake It” has nearly 40 million.)

This summer, seemingly retaliatory attacks have continued: In June, Lil Tjay, a 21-year-old crossover drill star, was nonfatally shot in the chest and neck in New Jersey; in July, 14-year-old Notti Osama was stabbed to death on a subway platform. DJ Drewski said the incentives to release insult-laden tracks remain in place, even as some rappers have second thoughts: “Artists hit me up. They’re like, ‘I got four more diss songs. After that, I’m not doing no more.’ They feel like that’s what people pay attention to. They look at YouTube numbers.” The very existence of Fivio Foreign’s recent hit “What’s My Name,” a romantic song that cheesily interpolates a Destiny’s Child chorus, is a symbol of his newfound stature.

Online, C-HII WVTTZ lives on. In February, the video for his song “Head Pop” was released on Kay Flock’s YouTube page, where it has gotten more than 3 million views, dwarfing the exposure he received while he was alive. As his death faded from the headlines, attempts to define his legacy also began to play out. “They took the wrong person 18 years old ambitious young king 👑 gone over the fiendish like craving we have for violence,” wrote Robert Ramaseur in a devastated remembrance he posted to his Instagram page. “I love you Jay.”

Williams, McKenley’s father, cultivating an online identity as C-HII WVTTZ pops, began posting unreleased tracks and tributes, including a shrine he made featuring sneakers, basketballs, and a framed proclamation in his honor from the State of New York. Williams has also started managing a 15-year-old from Florida who has adopted drill’s sound but wants nothing to do with gang life. “He might say, ‘If you come over here, I’ll do this to you,’ but he never did none of that stuff,” Williams tells me. “I deal with his mother and father; they don’t even allow that type of stuff. He found something that keeps him out of trouble.”

In July, Laura Gillespie, a humanities teacher at Children’s Village, forwarded me emails she and McKenley had exchanged before his death. He told her he would be going home in March. “That’s so great!” she replied. “There are not many boys who come and maintain good behavior their entire stay. To be honest when you first came I thought he can’t be this good, he’s gonna act up soon. And you never did!!!”

He wrote back that he planned to return to campus, telling her, “I came so far its no reason to mess up now ima stay as a day student so I can get my diploma.” He added that he was disappointed his classes wouldn’t be with her, as she had been assigned to teach a different grade. “i wish you could of stay with me 😢” Gillespie sympathized, inviting McKenley to come by her classroom anytime. “okay be safe,” he replied.

At a school holiday party in December, Gillespie took a photo of him: He looks sheepish, a blue surgical mask pulled under his chin. “I told him to smile,” she said, “because I was always going to remember him when he got famous.”

More on drill music

- Everything We Know About Sheff G and Sleepy Hallow’s Indictment

- A$AP Rocky Takes ‘Full Responsibility’ for Short Rolling Loud Set

- The Voice of New York Is Drill

- The Drill Songs to Know