This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

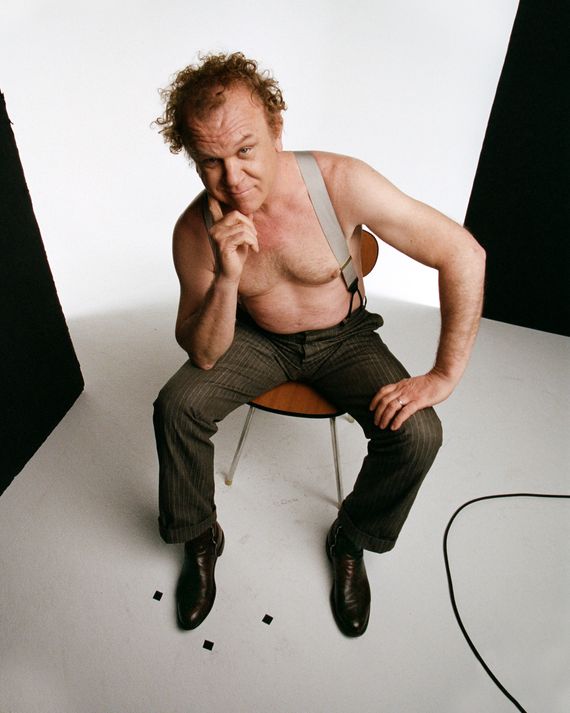

John C. Reilly has played lots of sidekicks, supporting the ambitions of great men like Dirk Diggler and Ricky Bobby. But in HBO’s Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty, he’s the one with the vision, starring as Jerry Buss, the real-estate mogul who bought the L.A. Lakers in 1979 and — with the help of cheerleaders (rare in the NBA back then) and a fast-break offense — turned pro basketball into a show. Winning Time executive producer Adam McKay directed pivotal Reilly performances in Talladega Nights and Step Brothers and here again shows us new sides of the actor (including most of his torso, on display under a period wardrobe of wide-open shirts). Over two conversations in mid-April, Reilly shared the secrets to a 70-plus-role career: It’s not the industry that typecasts actors, he said, “it’s the audience. If they don’t want to see you in a certain kind of part, you won’t be playing it for long. And my audience has let me do all kinds of different things.”

You were offered the part of Jerry Buss in Winning Time just a week before you shot the pilot.

That’s right. Seven days.

Buss seems like a difficult role to step into. He was a beloved public figure with a complicated personal life, plus in addition to owning the Lakers, he was a real-estate baron, chemist, aerospace engineer, and poker player. How do you become somebody like that in seven days?

First of all, I was lucky I kind of look like him with the help of hair, makeup, and the right clothes. Once I had all that, I was like, Okay, what did this guy do in his life? He passed away in 2013, and he didn’t write an autobiography, so I just tried to imagine what it felt like to be in his position. I had a lot of help from Jeff Pearlman’s book Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s and showrunner Max Borenstein, who did so much research. Plus Adam McKay and I had a common sense of humor about men in this era, about the entitlement and craziness of the male ego.

In some ways, I felt similar to Jerry. Like him, I wasn’t born with a silver spoon in my mouth — I come from a working-class family in Chicago — so I knew what it felt like to be an outsider who comes to L.A. seeking their fortune. He also reminded me of my dad, that generation of man that was unapologetically macho, that had seen real hardship. So I was intuiting my dad’s energy. The more layers of the onion I unraveled, the more I was amazed at how much I was already in the zone to play this character.

That still sounds like a busy week.

Actually, I also went to Nashville that week and played a couple shows with my band because I’d already committed to them. I was like, “Well, I can do a costume fitting on Tuesday, but I’m leaving for Nashville on Wednesday.”

According to Adam McKay, he and Will Ferrell had a falling-out because Will wanted to play Buss and Adam offered you the part without telling him first — but then you called Will and told him right away. I think it’s interesting you made that call. Do you think that says something about how you move through Hollywood?

I don’t want to give that any more oxygen. It’s a personal thing. Also, I had nothing to do with the casting decisions of this show before I was involved. If I got a role that any of my close friends had been interested in, I would let them know. That’s just the way I move through life, not the way I move through Hollywood. I try to do right by my friends. I try to do right by Adam, and I try to do right by Will.

You’ve played a lot of vulnerable men — say, John Finnegan from Hard Eight, or Officer Kurring from Magnolia — who put on a macho facade to mask their vulnerability. But Buss is more straightforwardly macho.

Jerry was a product of his time, but I don’t think he was especially macho. In my experience, macho people who are headstrong and think they always have the best answer are not the most effective leaders. Jerry was someone like me who was able to become a beta male when necessary. He knew when to defer to the women in his life, or to a player or coach with a big ego, when they had better ideas than he did. He could be like, “All right, you’re the boss. You’re the one who knows more about this. So you tell me, Jerry West, how do we put together a winning team?”

Speaking of Jerry West, Winning Time has come in for criticism for exaggerating the stories of the real-life people it portrays. Were you worried about blowback as you were making it?

The overall plot is based on historical fact, but we do fill in a lot of blanks. I knew it would be difficult for the people involved in this story to see their lives depicted in a semi-fictional way. But that doesn’t mean this story shouldn’t be told. The truth is these were crazy times. There was anger and betrayal, and the shit was hitting the fan. I respect everyone’s right to their own story, but I don’t think that precludes others from telling public stories. And this is a public story. People have said, “How can you tell the story of the Lakers without the Lakers themselves?” And my answer to that is, “How could you tell it with them?”

You recently met Buss’s daughter Jeanie, who is played on Winning Time by Hadley Robinson and is now herself the controlling owner of the Lakers. Did she give you any notes?

I went to a Lakers game and was in the lounge waiting for the game to start, and she came up to me and said, “Hi, I’m Jeanie Buss.” I was like, Whoa. I wasn’t sure if I was going to be thrown out of the building or what. She said, “Listen, the team’s not participating in the show, so I’m not here to say anything good or bad about it. But I wanted to tell you something personal: My dad knew who you were. He loved musicals, and he saw you in Chicago and really loved your performance as Mister Cellophane. He said, ‘See that actor? That’s someone that can make you laugh and make you cry. That’s the mark of a great actor.’ ”

Most of the actors who have made audiences laugh and cry did it in that order: They were comedians first who took dramatic parts later. There’s less precedent for actors who have succeeded in drama before embracing comedy as fully as you have. When you pivoted from movies like The Hours to ones like Walk Hard, did it feel like you were risking something?

No. It wasn’t like I was going to be disappointing so many people by being funny. And if I pulled it off, I’d be bringing them joy. An actor’s life is taking the most attractive opportunities you can get, and it just happened that comedy came my way. You can’t say, “No, I’m a serious actor. I won’t take that opportunity.” When people ask me if I prefer comedy or drama, I say, “I prefer being employed.”

You’ve said that before Winning Time, you felt like your career was “dead in the water.” How is that possible?

That’s the thing about actors: You can have achieved so much, but when you become unemployed, you don’t feel like a movie star — you feel like an unemployed actor. I was just sitting there thinking, Man, I got nothing going on. Because at that moment, I didn’t.

You were offered Winning Time not too long after the release of Holmes & Watson, which got pretty bad reviews. Did you learn anything from them?

I don’t pay much attention to the response to things. When I’m done, I’m done. You either like it or you don’t. Every movie is praying for a miracle.

You’ve been in movies across every possible genre. Now there’s a legion of John C. Reilly fans who have been conditioned to expect almost anything from you. Are there parts you think they don’t want to see you play?

Is there a legion? I don’t know. I’m not in touch with that legion, but I hope there isn’t anything people aren’t willing to let me do. That said, I do have things that guide whether or not I do a movie. A lot of times, it’s the worldview of the character. I’ve been offered roles of unethical people that are so far outside of my universe, like pedophiles and murderers. I don’t think it’s wrong to play those characters; I just don’t want to spend six months inside their heads.

So you wouldn’t want to play a Hannibal Lecter?

I think I was offered one of those movies at one point.

Really?

Yeah. But it depends where you’re at in your life. I don’t know that in the real world there are any real villains. That’s kind of a creative construct. When you actually meet people who have done bad things, you’ll see something human there. Everyone is born a baby, and I haven’t met an evil baby yet.

Do you have trouble separating yourself from a character after you finish a job?

At the end of a night, a violinist gets to put his violin in its case. If it gets broken, he takes it to the luthier and they fix it. But actors are their own instruments, and we have to perform maintenance on ourselves. You have to come back after these jobs that take a lot out of you emotionally. The physical wear and tear is another thing people don’t realize. It’s like, Just slam your hand on the table one time. No big deal. But then I slam my hand on a table 25 times from three different angles, so by the end of the day, it gets messed up.

What kind of maintenance did you have to do to get through ten episodes of Winning Time?

All the usual stuff, like taking care of myself physically. But one of the main things I had to meditate on was not letting the power of my position go to my head. When you’re on a show like Winning Time, it’s in everyone’s vested interest that you are happy and stable, so they’re always trying to make you feel important. I like to be self-reliant because you can get spoiled really quickly. Once, I was running lines in my trailer. I think it was one of the early scenes where I rip Jerry West a new one. And I realized nobody had come to tell me when it was time to go to set. I went to the ADs like, “Hey, why didn’t you guys let me know it was time?” They were afraid to knock on the door because they thought I was screaming at my assistant. I was like, “We were running lines! Come on, you guys. You know I’m not like that.”

You said there are elements of your real father in your performance as Jerry Buss. But some of your best scenes in Winning Time are with Sally Field as Jerry’s mother, Jessie, who loses her battle with cancer. Did you bring anything about your own mother to those parts?

Oh, absolutely. I don’t like to go into too much detail about my family, especially people who have passed away, like my mom. She certainly can’t give me the okay to talk about her private life. But she did pass away very suddenly. I had no warning at all. My dad, I had a little more warning. He was ill, so I had four months to get ready. But my mom, it just happened. When I got into those scenes with Sally, I realized, Oh my God, I have a lot of stuff unprocessed in here.

I went to see a shrink one time after my mom died because I felt like that’s what you’re supposed to do. You’re supposed to talk to someone when you go through a traumatic experience. But I didn’t really. I muscled through it. And I spent a number of years after that pretty depressed. I couldn’t have found a better partner to go back into that stuff with than Sally Field. I could really open myself up to her. She’s gone through these difficult conversations with her own children. I felt safe.

And then after those scenes, I found it was important to be honest with myself: You just went through something traumatic: the death of your mother. Even though you were pretending and it wasn’t technically your mother, it felt like it. So be nice to yourself tonight. Take a bath and then try to let it go.

When you’re channeling those intense emotions, is it hard to keep them under control for the good of a scene?

I was struggling every day to not be too emotional too soon: Jerry’s tougher than this, man. Hold it together. There’s a scene on an elevator between Jerry and his daughter Jeanie where he says, “She’s going to be fine. Pull yourself together.” And that was also me telling myself, You can’t fall apart. Jerry didn’t fall apart yet.

When you’re a young actor, you feel like the main thing is to crack open your heart and let out whatever’s in there. Be vulnerable. You’re trying to learn how to open up Pandora’s box at will. As you get better, the challenge becomes, How do I keep the horses in the barn until it’s time to let them out?

I learned how to do that by doing musicals. When you’re singing a song, you’re trying to keep it technically perfect and sing it with enough breath and stay in tune and pronounce the words clearly. But you’re also trying to emotionally experience what’s going on in the song, and if you get too emotional, you can’t sing because you start to blubber. It’s a great way to learn the disciplines of communication and feel and not to let one compromise the other.

There was a stretch between about 1989 and 2002 when it seemed like every top director wanted to work with you — Brian De Palma, Tony Scott, Paul Thomas Anderson, Terrence Malick, Sam Raimi, Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Rob Marshall, and Stephen Daldry. What was it like being that hot?

Well, those directors all discovered me one at a time. Brian De Palma literally did discover me, and after that, the others were like, “Oh my God, I found the perfect person for this role. I don’t know where this kid came from, but he’s perfect.” Paul Thomas Anderson was the first one who put it all together, who was like, “I know you from this movie, and this movie, and this movie. And I know you can do more than you’ve been doing, so I wrote this part for you.”

As an actor who’s been directed by lots of filmmakers, what do the good ones do for you? What advice would you give to a mediocre director who wanted to get the best possible performance out of John C. Reilly?

I can tell you what it’s like to work with Paul. He’s someone who’s so excited to see what you’re going to do next. That sounds like an obvious thing, but having one person’s complete attention while you’re acting is important. You would be amazed at the number of film sets where the director is looking at the monitor or worried about what the lighting or camera is doing. Where there’s no one emotionally connected with you to come up after the take and say, like Paul does, all sweating and excited, “Oh yeah, that was so cool. I saw that time you got a little more pissed off when you said that thing. Let’s keep going that way. That’s so great. Yes, yes, yes.” Martin Scorsese is the same way: He hires great people, and he lets them surprise him. I haven’t worked with many mediocre directors, but if I were to describe someone that way, it would be because they weren’t paying attention.

In 2003, your Gangs of New York co-star Daniel Day-Lewis won a SAG Award and in his acceptance speech he called you a “terrible man” because you have “this habit” of making other actors “look like they’re acting.” What did you do around Daniel to make him say that?

I could probably say the same about him. When you’re on set with Daniel, he is not there. When we were making Gangs of New York, he and I hung out a little on the weekends. I remember coming in on a Monday after having a playdate with our children — he’d been so lovely and gentle and he brought me a cup of tea — and I made the mistake of saying, “Hey, thanks for the great weekend.” Then he said, in the dialect of his character, “Fuck off, Jack.” He called me by my character’s name. I was like, Whoa, okay, message received. You’re not here right now. I get it. So at the SAG Awards, I think he just wanted to say something nice. I’ve never won an award, but that night I felt like I won the Daniel Day-Lewis Award. If that’s the only one I ever win, that’s enough.

What he said seems to imply there’s an understatement to your acting style. Do you think that makes it harder for the people who vote for awards to appreciate your work? They tend to go for flashy performances.

No, I don’t worry about that. I actually disagree with your premise. In my experience, people like it when they can relate to you. So when your character seems like an everyday person, or however you’d describe it, that creates more relatability and emotional connection.

You’ve told a story in a couple interviews about John Malkovich’s performance in the 1979 Steppenwolf production of Curse of the Starving Class. As the legend goes, he peed in character onstage every night, and you and other actors around Chicago were awed by that. No disrespect to John Malkovich, because that sounds tricky to pull off, but was there ever a point when you realized that level of immersion in a character wasn’t necessary for you?

Every actor is different. I only do as much research as I have to, to feel like I understand what a character did. Like, I understood enough about longline fishing to play the guy from The Perfect Storm. I familiarize myself with the character’s skill set but try to stay loose and improvisational enough to embrace the moment as it comes, to be alive on-camera, because that’s what the camera wants. The audience wants you to surprise them, to look like you’re not just doing something you planned to do but doing something right in front of them for the first time. That’s what makes acting compelling. But everyone I know who heard that Malkovich was able to pee on command onstage thought that was an amazing technical ability.

You once told Paul Thomas Anderson you were tired of playing “heavies” and “child men” and wanted to play a character who falls in love, and so he wrote your part in Magnolia. Do you think that movie changed the way audiences saw you?

I don’t know. I hope so, because that was a personal role and I really felt connected to it. Paul saw I was capable of doing more than character work, that I was someone who could carry a story. And actually, what I said to him was, “Hey, you’ve got to write me my Sunrise.” What I meant was a movie called Sunrise from the 1920s. It’s this romantic story. I can’t even remember what it’s about, but at that point, I had just seen it. Paul didn’t realize I was referring to that movie, so he wrote the scene at the end of Magnolia in the morning when the sun is coming up. He thought I literally was like, “Write me a sunrise.” He and I have actually never talked about that.

One movie that definitely changed perceptions of you was Step Brothers. When it was released in 2008, it seemed to come and go. It got mixed reviews and did fine at the box office. But since then, its reputation has grown, and these days it’s considered an all-time classic. When did you realize it was a big deal?

I could tell even at the premiere. Will’s mom was there with a bunch of her friends, so all of these older ladies were coming up to me like, “Oh, I just loved the movie so much.” I was like, “You did? Why?” I was worried it would be too crude for them. They said, “Oh, we just want to grow you two up.” I realized our characters were sweet enough that people could have maternal feelings toward them. And then 11- or 12-year-olds can also relate because our characters are pretty much kids.

Step Brothers anticipated some broader cultural trends. It came out just before the 2008 financial crisis sent a generation of young adults back home to live with their parents. A lot of millennials probably saw their futures in Dale and Brennan.

You’re right. Adam McKay tapped into this moment of infantilization, this idea in our culture that you have to be as hip as an 18-year-old for your entire life — you have to wear cool sneakers and the right concert T-shirt as an adult. Whereas my dad looked at that and was like, I don’t want to dress like a teenager. Teenagers are stupid. I’m a grown-ass man. I’m going to wear men’s clothes. I don’t give a shit what you think is hip. Now you turn on the TV and there’s no way to be a dignified grown-up. Everyone’s supposed to be as cool as their kids — and at a time when people in their 20s can’t even dream of finding an apartment, let alone buying their own home.

Is Step Brothers still the role you’re most recognized for?

In the whole time since the movie came out, I would say yes. But lately people are yelling “Dr. Buss” left and right because Winning Time is popular. My whole career has been like that. All of a sudden, people start mentioning a certain movie a lot. And then it turns out this cable station has been showing that movie for the past month.

Which movies are you proudest of?

I’m proud of everything I did. I have high quality control. But to give you an honest answer, the things I’m proudest of are the things I put the most personal stuff into, where I improvised or drew from my literal memories. That includes everything I made with Paul Anderson: Hard Eight, Magnolia, Boogie Nights. That includes Step Brothers, Talladega Nights, and What’s Eating Gilbert Grape. It includes Winning Time.

Boogie Nights is another movie of yours that’s had a long afterlife. Why do you think that one has endured?

Like all Paul’s movies, there’s some real stuff in there. It’s not really about porn; it’s about choosing your family. If your blood family doesn’t love you, you can choose another family. I know people in my own life who have done that, and that’s a very powerful, self-loving thing to do.

But there’s something else that’s interesting about Boogie Nights. When it came out in 1997, it already seemed like an old movie. It seemed nostalgic because Paul shot it on Super 35 film, so it looked like the ’70s and early ’80s.

Winning Time uses a similar trick to evoke its time period. It uses different film stocks and old broadcast cameras.

Yeah, we shot every scene with a 35-mm. camera and this Ikegami broadcast camera from the ’80s, which makes it all seem of that period. And then the DPs would run around grabbing close-ups with Super 8 cameras. I was unsure about it while we were doing the pilot. I thought, I don’t know, man. Is this going to be hard to look at, like a quilt or something? But it was a great device to take you back to how you might’ve felt watching this stuff in the first place. The lack of high-definition detail is like looking at a painting; you use your imagination to put things into it that aren’t there, like when you’re looking at an Impressionist painting and imagining what Gauguin was seeing.

There aren’t many TV shows shot on film anymore. Do you prefer it to digital?

Yeah. What 35-mm. film does to a film set is break it up into 11-minute chunks, because you can’t put more than 11 minutes’ worth of 35-mm. into a magazine. So no matter what happens in a take, when that film runs out, you have to stop. I’ve done movies that are just digital, and it’s very hard to maintain the moment between “Action” and “Cut” because it doesn’t end — it goes on and on. You’re 20 minutes into a take and you hear people outside the set walking around because they have to go to the bathroom.

The moment between “Action” and “Cut” is sacred. Everyone has to shut the fuck up for a second and give focus to what the actors are doing. Otherwise, what have we been preparing eight months for? We spent all this time, money, energy, and planning — location scouting, building sets, all of it — to get to that moment when the director says “Action.” So it needs to be this heightened moment where we try to tap into something bigger. If it just seems like 30 minutes while we’re riffing, it loses some of its power.

As an actor accustomed to movies, what surprised you about making a TV series?

The biggest surprise for me was the lack of final cut for directors. I guess it makes sense: These are directors hired to come in and direct a couple episodes, so they’re not in the same position as Adam McKay or executive producer Rodney Barnes to decide what the arc is going to be. That took getting used to because the way I work is I get involved with the director. I’m a loyal soldier kind of actor. I have one authority on the set. So I went up to each director and said, “Listen, you’re in charge. I’ll do whatever you say. If you have a vision for the way this should go, I’ll stand with you.” And sometimes they’d say, “Yeah, but John, after my first cut, I’m literally not part of the conversation.” And I’d say, “Yeah, but if you want to be, I’ll advocate for you.” I think that meant something to them because they come in, there are all these famous actors, and it can be hard to feel like they’re the boss.

Winning Time is a gender and racially diverse show in front of and behind the camera. Looking back on the sets you’ve been on over the past 30 years, how have things changed from your perspective?

When I started doing movies, it was all white men. If you’re away from home for six months, it’s not that fun to spend all of your time with just men or people of the same race. Certain departments have always had women, but the camera departments had barely any women for the first 15 or 20 years in my career. That was a bummer. Men can get pretty crude, and it ends up feeling like the Army.

With Winning Time, the story of the Lakers and of basketball in general is one of racial politics. The NBA at different points would have liked to have ignored that, and you can’t. That’s what was going on on the courts in 1979, and racial and social justice is part of the game right now. For me, it was like, Finally, there’s representation in these stories that we’re telling — we’re looking at a working-class Black family in Lansing and the life of a super-intellectual Muslim guy who was a leader in thought in his era. It’s more interesting than the same old white-guy stories.

The show was recently renewed for a second season, and in theory it could run for a while. Is it daunting to think Buss is a role you could be playing for years?

I’ve never played a character for this long in a movie or play, and it took a certain amount of emotional stamina to hold on to Jerry for ten episodes. It’s above my pay scale whether HBO wants to get into the Shaq and Kobe era, but I’m only obligated to do another season of the show, and I haven’t even thought about whether I would want to keep doing it beyond that.

This is sort of a random question, but you made a cameo on A$AP Mob’s 2017 album, Cozy Tapes Vol. 2: Too Cozy. How did that happen?

Well, for some reason, rappers love me—I think it has to do with Step Brothers — which is great because I love rap too. I was in London and a friend of mine was like, “Hey, man. I’m at a recording studio two blocks from you with A$AP Rocky. You want to meet him?” I texted one of my sons, “Who is A$AP Rocky?” And he was like, “Oh my God, he’s a hero of mine.” So I met him, and he was just so lovely. First of all, he’s so handsome. You’re like, Wow, I’m meeting the Black Montgomery Clift here. He and his producer played me all these different tracks. Later they texted me, “Hey, would you ever want to do a sketch on one of our records?” So they explained the concept of the whole thing—“Yamborghini High,” the album being like a high-school effort—and I was like, “Well, I’ll be the principal.”

While I was preparing to talk to you, I watched Boogie Nights and Stan & Ollie on the same day. They don’t have too much in common, but they’re both about sea changes in the entertainment industry and performers at the end of their eras. What do you, a movie star, make of the sea change we’re in now, as all of the attention moves to streaming TV?

I once might have said, “I don’t know if TV is ever going to be as good as a movie. With advertising and commercial breaks and the speed at which TV productions work and the way budgets go, there’s just less focus on quality.” But then I saw Escape at Dannemora and realized I was wrong. If you have a film director and amazing actors, why wouldn’t you want a story to be seven hours long? And then when corona kept everyone out of movie theaters, that was a nail in the coffin. It was a shock to the system when the ArcLight went under. Everyone was looking like, Wait, what is going to happen here? I think it might be time to start calling this business something else. It’s not the film business. It’s not the TV business. It’s computer vision or something.

Do you have anxiety about the shift?

I don’t feel anxious about it. One of my favorite sayings is, “Worry is negative prayer.” In other words, it is like praying for the thing you don’t want to happen. I try to imagine the way I want things to go and then put in my time into meditating on that. Novels didn’t destroy the short story, and streaming TV shows will not kill the movie. There’s something great about seeing a story play out in 90 or 120 minutes. That’s about as long as we want to sit still.

More Conversations

- The One and Only Benedict Wong

- Made for Jessica Lange

- Michael Mann’s Decadeslong Drive to Make Ferrari

Amos “Mister Cellophane” Hart. According to Rotten Tomatoes, the 2018 comedy is Reilly’s worst-reviewed movie. The real Jessie Buss died years before the events portrayed on Winning Time. Reilly got his first big break in De Palma’s 1989 film, Casualties of War. He’d been hired for a small role and was promoted to one of the leads. The 2000 Wolfgang Petersen movie based on the true story of a fishing boat lost at sea during a 1991 storm. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans is a 1927 romantic drama directed by F. W. Murnau about a woman (Margaret Livingston) who woos a farmer (George O’Brien) in hopes that he will murder his wife (Janet Gaynor). New York’s David Edelstein called Step Brothers “gorgeously controlled pandemonium,” but Roger Ebert’s review was less effusive: “Sometimes I think I am living in a nightmare. All about me, standards are collapsing, manners are evaporating, people show no respect for themselves.” Six of the ten Winning Time episodes are directed by POC, and four are directed by women. “Good morning, Yamborghini High students, faculty, and staff. Welcome back, returning students — and welcome, new students. This is Principal Daryl Choad, and these are the announcements for today, our first school day of the new year. Just a reminder to students with drama on their minds: Auditions for the school play Bad and Boujee are being held after school today.” The 2018 movie about the final years of comedy duo Laurel and Hardy, in which Reilly plays Oliver Hardy to Steve Coogan’s Stan Laurel. The legendary Hollywood multiplex that closed its doors in 2020.