Keith Knight is the co-creator and executive producer of the new Hulu series Woke, which debuts today and is loosely based on Knight’s life and work. This is Knight’s first television credit, but he didn’t come out of nowhere. He’s been a cartoonist with more than two decades of work to his credit. His cartoons have been featured in The New Yorker and Mad magazine, and he illustrated the Jake the Fake book series, co-authored the book Beginner’s Guide to Community-Based Arts, writes and draws two weekly comic strips (The K Chronicles and (th)ink), and last year ended his daily comic strip The Knight Life after 11 years.

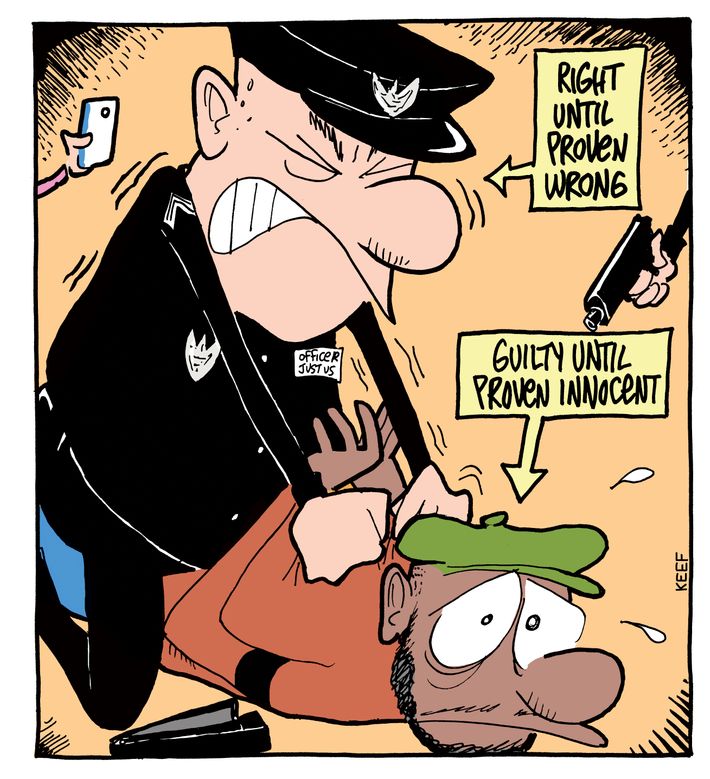

Woke stars Lamorne Morris (New Girl) as Keef Knight, a character Knight describes as a younger, more naïve version of himself. The show also stars Blake Anderson (Workaholics), Rose McIver (iZombie), and Sasheer Zamata (Saturday Night Live). The show introduces Keef as a largely apolitical cartoonist who gets traumatized after being profiled and detained by the police, which blows his life up in different ways. The series isn’t solely based on any story or book that Knight has done, and it uses his characters — like Knight himself, and his friends Clovis and Gunther — who don’t necessarily appear as they do in the comics, but the show is infused with his sensibility and approach. Woke is a comedy about police brutality, social issues, and the experience of being Black in America. It’s a fine line to thread, all while mixing high and low humor, nerd culture and Black culture, punk and hip-hop. Knight recently spoke with Vulture about translating that vision to television.

How did you end up making this TV show?

The producer John Will approached me. He really dug my stories. John started working with the actor Eric Christian Olsen from NCIS: Los Angeles. He was starting up his own production company and he brought it to one of his buddies, Will Gluck, who had his own production company, which had some sort of deal with Sony, and Sony dug it. This was after I moved to North Carolina, so I came to L.A. to interview a bunch of different writers. Marshall Todd came in, and he was one of the guys who co-wrote Barbershop back in the day. His script resonated with me because it was very different.

A lot of the scripts I was reading had these racial tropes of “white girlfriend brings Black boyfriend to meet white parents.” Silly stuff like that. Marshall’s script opened with somebody doing rails of cocaine off the glass of a gun shop, and it just got crazier from there. [Laughs.] I just remember calling John up and going, “I think this is the guy.” I gave Marshall a bunch of my books, and I think he was the one who came up with the premise of this traumatizing incident that triggers this “woke” vision, and since he’s a cartoonist, inanimate objects come to life. We just went from there. Marshall really infused Clovis with this personality, because he’s not a character like that in the comics. It was important to show two very different Black men.

This is something comedians might be able to relate to more, where a producer was interested in your sensibility and it was about finding a way to build a show around that.

I have to give thanks to Tom Gammill, who’s a cartoonist and a television writer. He worked on the Harvard Lampoon, Seinfeld, SNL, he still writes for The Simpsons. He’s like the Forrest Gump of classic comedic television. He said to me early on — and I have to give credit to him because he was so smart in saying, “It doesn’t have to be animated. You can take your sensibility, and it doesn’t have to be a cartoon and he doesn’t have to be a cartoonist as long as you have your humor in there.” He made it sound doable in ways outside of what I was thinking. I think everybody who came on the show did that: expanded the idea of what it could be.

Did you always want to be hands-on at every step — not just writing it, but being on set during the shoot and overseeing the editing and animation?

I just heard about people who sell their stuff to Hollywood, and they have nothing to do with it and then someone takes and just wrecks it. I didn’t want that. If it was going to get wrecked, I wanted to have a hand in the destruction of it. [Laughs.] I have this particular style of mixing highbrow and lowbrow, of having serious issues with a lot of humor. It’s this fine line that I thought I needed to be there to make work. I don’t think that my sensibility would have translated if I was not there. The same thing with Mo — Maurice Marable — the director-producer. I think more than anybody else on the project, he understood what I wanted to do.

What did Marable bring to the project?

He elevated it by suggesting we use puppetry and all sorts of animation that really looked like it was living in the world. So the bottles that come to life are real bottles. The trash cans are real trash cans. It’s so much better than it would have been if it was just 2-D animation. When he suggested this Michel Gondry–type of style, that just made me go “Yes! Yes!” [In] his look book, which is how you pitch what you want things to look like, he suggested Amelie, Do the Right Thing, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and Sorry to Bother You. So magical realism. It just made me excited. And that’s what you want to do: Every time you add someone to the project, you want it to get better and better and better.

It must be so different going from writing comics on your own to working with other people to translate your vision into a show.

It’s totally different, because there’s so much out of your hands. You just have to trust that you have talented people, and there were a lot of talented people around. There were plenty of people saying, “I don’t know if you’re going to be able to pull this off,” especially with the animation. We wouldn’t show executives stuff where the animation wasn’t done yet, because it looked silly when it was just somebody behind a trash can moving it around. You have to show them the finished thing so they get it.

I remember we were looking at sets for the comic-book shop and being taken to a comic-book shop and saying, “This is too mainstream. It’s got to be a hole in the wall.” They said, “Well, we can’t fit all the equipment into a hole in the wall,” but they found a much smaller comic-book shop. They painted it some cool colors and the owner was psyched. I just remember walking into the production office in the warehouse. I loved walking through the whole place and saying hi to the props people and the people that write the checks and the people who build sets and talking with all these different people. It was so fun to know you’re giving work to all these people.

Was it hard to hire writers and allow them to write “you”? Because the show is “yours,” but it’s also not yours.

I had no experience in it, so I didn’t have much to do with hiring the writers. I think I’ll have a lot more to comment on next time around, but we had a diverse writers’ room. I’m spoiled — I only know a writers’ room that consists of mostly women of color. We had a Black female casting director and two Black directors, and we tried to have as diverse a production crew as we could. It would be nice to have an even more diverse production crew. I think it’s important, because Hollywood is all about who you know. To break in, you’ve got to give somebody a break.

So much of the coverage of the show has been about the big ideas, which are important, but it’s not just a show about social issues.

A lot of journalists asking about the show are putting way too much on us: “Is this going to change the world?” We’re not out to change the world with the show! We’re out to make people laugh, and take the piss out of a few things, and make you think. The gatekeepers that allow TV to be created have only let a certain image through to the public of what Black creativity is. When my wife first met my family and friends, she said, “It’s funny, Black people in real life don’t talk like Black people on TV or in the movies.” When we got interviewed recently, this guy said, “I’ve never seen anything on TV like this. You’re mixing magical realism with Black characters.” I think for a lot of people, Black characters have to be in an urban setting, and it can’t be fantastical. It’s a nice combination of bringing Black culture and nerd culture together. I hope that the success of the show opens the door for more ideas and more folks to come in.

We’re at a point where these ideas and concerns you’ve been writing about for years are suddenly everywhere. What is the role of humor in these conversations?

What its role has always been. Cartoonists are the modern-day court jesters. Humor helps folks deal with serious issues. I’d like to think that the show itself is an extension of my work in print, which is to use humor to approach these serious issues. Like my comics, I want the show to make people laugh first, to make people think second, and third, motivate people to do something, whether that means speaking out, or joining something, or donating something, or creating something. That’s the important thing to me.

If you had to give advice to a younger you, or a younger cartoonist, what have you learned? What did you take away from the process?

The advice I always give to everybody is: Tell your authentic story. Because if you don’t, someone else will, and they’re going to screw it up.

The other thing is just be nice to people. People want to help you if you’re nice. You hear these horrible stories about asshole directors or producers or actors, and it was nice to be surrounded with a lot of nice people. You want them to do well. So, be nice, and tell your story.

This interview has been edited and condensed.