In a ritzy suburban home outside Nashville with a turret, a wine cellar, and an anachronistic Tuscan motif, 55 of Santa’s helpers are spending the already humid Christmas morning (here, every morning is Christmas morning) building lighting rigs, ensuring the nutcrackers flanking the front doors are symmetrical, drinking bad coffee, and hanging up tinsel, wreaths, and a large banner welcoming everyone to “Santa Bootcamp.”

I’m standing a few feet away from Melissa Joan Hart, who graduated from Sabrina the Teenage Witch to Lifetime Christmas-movie lead to Lifetime Christmas-movie director. Santa Bootcamp will be her third Christmas movie in the director’s chair (her most recent, Feliz NaviDAD, stars Mario Lopez as a widowed high-school principal who has lost his Christmas spirit), and she has only 16 days to make the holiday magic happen. So “Action!” she calls, and a bubbly woman dressed as an elf (What We Do in the Shadows’ Marissa Jaret Winokur) throws her arms open and says, “Welcome, new campers!” to a group of smiling background actors. It’s hard to make out the dialogue over the sound of cicadas reminding us that it’s still summer. A bald crew member in a black T-shirt aims a leaf blower at Winokur, and her Santa Bootcamp sign-up forms swirl into the air as if shaken in a snow globe. Then it’s “Cut!” and time to reset the stack of papers to do it all over again.

Between takes, the bootcamp recruits in their festive knits shvitz in the sun; one dabs at her face with a handkerchief. The leaf-blower man crouches attentively. We’re almost ready to roll until — “Hey, can we have quiet from the trolley?” There’s an old-timey streetcar parked in the circular driveway for a scene that just wrapped, and the driver is watching TikTok videos with the sound all the way up. “Okay, quiet!” I’m not acting in this scene, so I try to open my bag of Sun Chips as silently as possible. A set decorator quickly lint-rolls Winokur’s elf suit. “Take No. 6.” “Take No. 7.” “Take No. 20.” Making Christmas happen is more tedious than you’d think, yet the television industry makes it happen dozens of times a year, every year, because the Christmas Movie Industrial Complex is one of the most predictable, profitable segments of the television universe.

As streaming eroded cable’s cultural primacy and romantic comedies all but disappeared from movie theaters, Christmas films have become a thriving source of romantic comedies and original cable programming. Last year, MGM and Walt Disney Pictures each released nine new films. Paramount released 12. The Lifetime Network released 35, and those were just the ones about Christmas. Together with the Hallmark Channel, UPtv, BET, Netflix, ABC, and Great American Family, there will be more than 150 completely new Christmas movies released this season. The networks are all a little different: Lifetime has embraced diversity, particularly with gay and lesbian lead characters, while Great American Family, Candace Cameron Bure’s turf, doesn’t make LGBTQ Christmas movies at all; Hallmark is known for Balsam Hill artificial-Christmas-tree product placement, while Netflix is known for self-referential Netflix product placement. But turn on your TV anytime in November or December and you’ll find a story about a workaholic woman who has neglected the things that truly matter in life — Christmas and men — until she finds both in a small town.

TV Christmas specials aren’t new (just ask Dolly Parton, Cher, or Cindy Lou Who), but in the 2010s, cable networks were incentivized by advertisers to produce more original content. What safer programming is there to sell Toyotathons and Happy Honda Days and Lexus Decembers to Remember against than feel-good holiday movies? The endeavor has produced more green than Taylor Swift’s family Christmas-tree farm … or Taylor Swift’s holiday single “Christmas Tree Farm.” In 2020, Hallmark’s parent company, Crown Media, made a reported $200 million in ad revenue in the holiday-dominant fourth quarter, more than in its second and third quarters combined.

These movies are audiovisual Christmas ornaments. Lifetime’s executive vice-president and head of programming, Amy Winter, tells me the archetypal Lifetime Christmas-movie viewer is “a woman who values family, whether the family is still in their home or coming home for the holidays. These women love the companionship of these movies to have on during the day.” Just as these films have become reliable advertiser bait, they have become part of viewers’ holiday routines — including mine.

I love Christmas the way only a Jew can. I grew up with nose-pressed-against-the-glass envy of the sparkliest December holiday, the one with the pretty songs and twinkly lights, the one that took as its mascots a jolly toy man and a magic baby rather than an insurgent militia leader. I started watching made-for-TV Christmas movies in my early 20s when former Disney Channel Original Movie stars made the extremely lateral move to the holiday sector. Did I know a single role Lacey Chabert had outside of Mean Girls? No. Did I delight in watching her play a meek web designer who makes A Wish to Santa for courage and ends up falling in love with her boss? Of course! These movies do not seek to win awards or impress Film Twitter. They aim to be the perfect background noise while you apply makeup for a holiday party you don’t want to go to or fight with your sister on the phone about your white-elephant exchange.

A cynic could say these films feel paint-by-numbers. But no two snowflakes are alike, even when those snowflakes are movies called A Christmas Prince, Christmas With a Prince, and Inventing the Christmas Prince. And for superfans, pointing out the similarities and differences is part of the fun. I have created taxonomies of the new releases, sorting them into subcategories including Old Hometown Flames, A Charming Inn, Sexy Amnesia, It’s Ironic This Romance Writer Is Single, Let’s Create the Perfect Conditions for Intimacy Using a Snowstorm, and It’s Not Catfishing If Your Hidden Identity Is Santa.

These movies do not simply arrive on my parents’ TV or Jodie Sweetin’s IMDb page fully formed. To learn how they are made, I decided to embed with one. Does a single big-city journalist going to a town with a Christmas-oriented economy to get “the scoop” sound like the plot of a made-for-TV Christmas movie? Absolutely. It has been the plot of at least a dozen, including Random Acts of Christmas, Christmas 9 to 5, Christmas She Wrote, The Christmas Edition, and The Christmas Yule Blog.

I found a willing host body in Santa Bootcamp, which is set to air in November, and was hired as one of several extras who will regularly appear in the background to make the titular bootcamp feel bustling. I wasn’t asked to provide a headshot or measurements, so I have to imagine someone in production has cyberstalked me to make costume size guesstimates. The film is about an event planner named Emily (The Walking Dead’s Emily Kinney) who is sent to a holiday bootcamp to find the perfect Santa for a Christmas gala to be held for investors at a very important mall. While there, she meets a hunky guy named Aiden (Days of Our Lives’ Justin Gaston) who may be just what she needs: not a mall Santa but a lover. The bootcamp is run by an elfin Christmas expert named Patty (Winokur) and a magical Christmas drill sergeant, Belle (bearing a suspicious resemblance to one Mrs. Claus), played by Rita Moreno: EGOT winner and recipient of a Peabody and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. She was recently the highlight of Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story. Here, she will be the highlight of a movie about a bootcamp for Santas.

Rita,” a worried-sounding producer says into her cell phone with a sigh, “went to the wrong Hilton.” I’m in the lobby of the hotel where the majority of the out-of-town cast and crew are staying, about 20 minutes from set. This is but a minor snafu. In fact, many Christmas movies begin with someone arriving at the wrong hotel or getting double-booked and having to sleep on a hunk’s couch. This is just life imitating Lifetime. Someone else at the hotel says this project is already going far better than Mistletoe in Montana, which she calls “the movie that shall not be mentioned.” Over the next few days, I will hear it mentioned at least twice more.

I carpool to and from the Santa Bootcamp base every day with two producers, their intern, and the movie’s screenwriter, Michael Murray, who has written 14 made-for-TV Christmas movies. An executive producer named Gina Rugolo is behind the wheel. “I love Christmas. I’m the queen of Christmas,” she says. “This is a dream job.” (She tells me she walked through the whole airport the other day in a Santa mask. “Nobody noticed.”) I sit in the back seat with another producer, Irene Dreayer, whose specialty is even more specific than Christmas movies: “I’ve created five shows with twins,” she tells me, citing Sister, Sister and The Suite Life of Zack & Cody. Dreayer says the people at Disney once asked her, “What do you do? Sit outside the maternity ward?”

I congratulate her on how her Disney Channel kids seem less screwed up than most. Tia and Tamera Mowry, for example, have robust careers starring in made-for-TV Christmas movies. (At least once, Tia’s Lifetime entry has gone up against Tamera’s Hallmark one.) These films are safe landings for child stars of the ’80s and ’90s; this is a genre where “A-list” usually means Lopez and Cameron Bure. Santa Bootcamp may not feature a former sitcom child star in front of the camera, but there is one behind it. Hart began directing in her early 20s on Sabrina, and she now regularly directs episodes of The Goldbergs and Young Sheldon. Between directing, producing, and acting, Hart tells me she must have been in “ten or 12” TV Christmas movies, beginning with an NBC one-off called Christmas Snow when she was 10. In 2007, she starred in ABC Family’s Holiday in Handcuffs, in which her character has a psychotic break and kidnaps Lopez. It scored the biggest ratings in the network’s history. In 2014, her company Hartbreak Films produced its first Christmas movie for Lifetime: The Santa Con, starring and directed by Hart and featuring Family Matters’ Jaleel White.

In this parallel Hollywood universe, a Sabrina-Urkel pairing is as big as Julia Roberts and George Clooney, and the success of The Santa Con led to Hart’s starring in a TV holiday movie every season since 2016: Broadcasting Christmas (she falls in love with rival newscaster Dean Cain), A Very Merry Toy Store (she falls in love with rival toy-store owner Lopez), A Very Nutty Christmas (she falls in love with a sentient nutcracker), Christmas Reservations (she falls in love with her ex now that his wife is dead), Dear Christmas (she falls in love with firefighter Jason Priestley), and the dreaded Mistletoe in Montana (she falls in love with a single dad vacationing on her ranch).

Hart calls these movies a “safe place to go” for viewers. “It’s the one time a year where maybe you turn off your true crime, or you’re not watching Housewives. You disconnect from all of that and get to this one safe space of cinnamon smells and pretty, twinkly lights,” she says. “I also think the holidays bring a lot of sadness. People are celebrating it for the first time without a loved one, or just had a breakup, or are struggling through a health problem, or are just depressed. These movies are an escape.”

Once on set, I’m thrown into the action-packed world of background acting for a scene in which I’ll play one of Belle’s helpers (not Santa’s helpers, which for Lifetime is a radical act of feminist praxis). We’re dressed in bright-green Alex Mill–meets–boiler-mechanic jumpsuits. Five of us will deck the halls in a time lapse that we’ll have to get right in one long, 15-minute take, after a shot of Moreno summoning us with the words “Let there be Christmas!”

Hart will later tell me that the shoot schedule on this kind of project used to be 20 days. Now it’s down to 16. “Do you want it good, fast, or cheap? You can pick two,” she says. “And of course, these are always done fast and cheap.” I learn that my fellow extras today aren’t actually extras at all: They’re members of the art department pulling double duty playing helpers decorating the room while decorating the room for real. The paid background actors won’t start until tomorrow, which frees up a little bit of the budget. Today, it’s spent on props like a vintage radio (so Gaston can do a wiggly dance to “Jingle Bells”) and a carton of rubber eggs. (Tommy from the art department yells “Think fast!” and tosses one at me underhand in what I’ll consider my on-set hazing.) Ashley Baker, the prop master, tells me that roping in crew members to fill out a scene isn’t uncommon on these productions and that she has been an ad hoc extra before, though the last time it was a movie about a stalker and she had to be an extra in jail.

Crew members aren’t the only parts of this production doing double and triple duty. This single-family home has been turned into an ersatz Silvercup Studios: The mud room is a production office, the living room is video village, the front porch is craft services, the side yard is the prop closet, the basement is wardrobe, and the upstairs is dressing rooms for the stars. Every other room functions as a multi-purpose set representing the titular Santa Bootcamp, Santa’s workshop, a lounge, and an enchanted library.

The mansion is loaded with the homeowners’ Christian art and décor, all kept strategically out of frame for this decidedly secular production. Anything that threatens to put the Christ in Christmas — a praying Virgin Mary statuette, a Last Supper carving at the base of a fireplace, a massive framed portrait of two children assembling a Nativity scene — is hidden. The craft-services coordinator tells me she likes that this movie, unlike Nashville’s many faith-based productions, doesn’t begin each morning with a prayer circle. Amen.

There’s an energy shift on set when Moreno arrives. “Good morning, everybody!” she says in a stage voice. “I’m Rita!” We all know she’s Rita, and I suspect she knows we all know she’s Rita. While the crew sets up the camera on a large dolly track, Moreno chats with us jumpsuited stooges. She is 90, and she declines multiple offers for a chair. We stand in a cluster, talking about meditation (“What it does is it dispels anxiety in a major way,” says Moreno), the fact that the boys are uncomfortable in the crotch of their costumes (“That’s the problem with jumpsuits,” says Moreno), and how she doesn’t drive anymore, though she’ll have to use a golf cart in the film (“I’m not thrilled about driving that fucking thing,” says Moreno). She is open and chatty and wants to know if we have any pranks planned. “I love mischief,” she says with a twinkle in her eye that would make Santa blush.

When we start rolling, Moreno delivers her line 20 different ways (“Let there be Christmas!” “Let there be Christmas!” “Let there be Christmas!”), then Hart films us decorating the hall. Her attitude while giving direction, to both actors and camera-people, is efficient and calm. She calls to us by first name and is obviously having fun with it: “Tommy, that wreath can use more sprigs!” “Rebecca, go inspect the nutcrackers!” I don’t know how to inspect a nutcracker, so I tap on its head and stroke its beard, drawing for inspiration on my lifetime of pretending to look productive while actually doing nothing.

As the crew sets up in the kitchen for the next scene, I overhear Hart telling Moreno about a production last year where there were “COVID cases on set, grizzly bears because it was Grizzly Bear Alley, one horse wrangler for nine horses — ”

“And a budget of two dollars and 25 cents,” Moreno jokes. They’re talking, of course, about Mistletoe in Montana.

Santa Bootcamp’s romantic leads arrive a bit later in the day looking exactly like a romance-novel cover: Gaston has a surgically precise five-o’clock shadow that’s pronounced enough to let you imagine he could sweep you away on a horse but not so scruffy that it would put off your conservative grandmother. Kinney has the requisite TV blowout curls and eyes the size of tree ornaments. They’re rehearsing a romantic scene in the kitchen in which Aiden wraps his arms around Emily and helps her knead dough, Ghost-pottery style.

I spy lush Nancy Meyers layers — a cream-colored cowl-neck and a flannel shirt — on a costume rack and ask if there’s a standard-issue uniform for holiday-movie leads. The wardrobe person tells me they go by what the script suggests: The leading man for Santa Bootcamp was described as “ruggedly handsome,” and the female characters are always “ambitious.” I point to a sparkly midnight-blue velvet up on a shelf and ask what it’s for, but it’s not part of the production at all. “The owner of the house’s daughter actually has her own line of designer leggings,” she tells me. “Wiz Khalifa performed at her birthday party.”

On the second day of filming, six extras arrive (the call sheet accounts for only five, and the sixth gives off major “Please don’t interact with me” vibes that the rest of us respectfully heed). In Los Angeles, background acting can be a full-time job. Producer Rugolo tells me her brother started working as an extra at age 50. “In sitcom pre-shoots, actors forget to hold for a laugh.” That’s where he comes in as a “professional laugher.” He can also do drama. “He’s died more on Grey’s Anatomy than anybody else.”

But here in Tennessee, the jobs are scarcer and the pay is worse, so background acting is treated more like gig work. As we suit up in the basement, another background actress, Jenna, tells me she’s a stay-at-home mom who loves Christmas and likes to watch how movies get made. Fittingly, she has naturally rosy cheeks and tells us that outside of extra work, she likes to take her daughter to a farm for “cow-patty bingo,” which involves drawing lines in the grass and waiting to see where cows stop to do their business. Another background actress named Raphinette likes that she can watch the movies she acts in with her nieces and point herself out in scenes. A soft-spoken military veteran, she notes that our bootcamp fatigues are all wrong: “These have zippers, but our pants all had buttons.” They probably didn’t have shirts with big red Christmas ornaments printed on the backs, either. Jai, who shows up every day dressed impeccably, swaps his silver-glitter oxfords for Army boots. He’s hoping to make it in the industry and has already had some local commercial work. A Willie Nelson look-alike named James tells me he’s a retiree twice over but likes background work because he gets to meet interesting people. “I’m usually a drunk, a homeless guy, or a cowboy,” he says. Background actor Todd hands me his phone and says, “I’m thinking of getting this tattoo. Should I get it?” It’s a picture of a stomach tattoo surrounding a guy’s belly-button to make it look like a monkey’s anus. As long as he’s not asked to do a Santa Bootcamp nude scene, I don’t see the problem with it.

We’re cut off by a PA who calls us upstairs to film in Moreno’s magical library (of course this house has a study lined with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves). This is the big group scene for the afternoon, in which Winokur, who originated the role of Tracy Turnblad on Broadway and is therefore my most-played singer of fourth grade, gives a speech. The extras’ job is to sell the idea that this home office is Hogwartsian in scope. We do this with lots of silent oohing, aahing, and nodding along while Winokur tells us about the wonders we’ll find in its tomes. When the camera rolls, her theater training leaps out; she gestures broadly, makes cartoonish facial expressions, and projects that we have “one hour to explore!” to the nonexistent cheap seats. “Marissa, can we do 75 percent on this next one?” Hart asks after she calls cut. Winokur dials it back just enough as she pulls a book off the shelf and says, “A Christmas Carol: Charles Dickens. They say that Belle was his muse.” This last part is said in a way that suggests Belle was Dickens’s lover: the slash fic I didn’t know I needed.

Considering these movies’ squeaky-clean image, I ask Murray, the screenwriter of Santa Bootcamp, about network notes and censorship. Is it okay to joke about sex with a ghost? He says he always knows that one or two lines won’t make it into the final production and tells me a story about one made-for-TV movie he wrote eons ago in which a character quotes the song “Tits and Ass” from A Chorus Line: “They had never said tits on this network before, so standards and practices came up with this list of alternative terms. And one of them was snack trays!” We agree that euphemisms almost always sound far more perverted than the words themselves.

There’s a PBS special from 1996, narrated by Maya Angelou, called Elmo Saves Christmas. In it, Elmo wishes it were Christmas every day but learns this would be a bad thing for many reasons (one is that the Easter Bunny, played by Harvey Fierstein, would be out of a job). By the third day of making a Lifetime Christmas movie, I relate to Elmo.

Today, Hart has to shoot six scenes, including what is arguably the most important in a made-for-TV holiday movie: the meet-cute. This time, busy bee Emily meets hunky caterer Aiden while he’s hauling produce off a truck bed, signifying both strength (he’s lifting crates!) and sensitivity (he’s delicate with the Anaheim chiles!). Because female leads’ character traits often amount to “busy” and “klutzy,” Emily falls and Aiden catches her. They run this scene possibly a dozen times. “In one of the takes, she tripped and fell for real,” Gaston tells me later. Christmas is a contact sport.

These films rarely, if ever, take place in the sort of car-based suburban sprawl where the majority of Americans live (and where we’re filming). Instead, they’re located in a small town with a walkable Main Street lined with charming businesses. In the long shadow of You’ve Got Mail, these quaint shops and inns are often threatened by a land developer or conglomerate with more capital than heart. These small family businesses’ fictional struggles are then interrupted by commercials for Walmart and Amazon. It sounds counterintuitive, but it feels seamless in the moment; by virtue of buying ads during these movies, the brands manage to align themselves in the back of your brain with the good guys.

Plots about struggling family-run inns aren’t going anywhere, but the people who fall in love at them are becoming more diverse. Murray wrote 2020’s The Christmas Setup, which features Fran Drescher as the lead’s meddling mother; this movie received more press and acclaim than most because it’s funny, sweet, and the first on Lifetime to star two gay leads and tell a gay love story. Murray says he tried to get a gay Christmas movie into production for years and found this network was the more open-minded of the Big Two. Last year, Murray followed The Christmas Setup with Under the Christmas Tree, a rom-com for Lifetime lesbians. He tells me he wrote a small beat in which one of the women takes a bobby pin out of her hair and puts it in the love interest’s. “It was this sensual moment,” he says, but the shooting schedule was tight and it got cut. He’s still not over it.

I ask the production designer, Robert Wise, a focused man in a porkpie hat (his filmography includes The Trouble With Mistletoe, Romance at Reindeer Lodge, and Hollywood Sex Wars), what sort of changes he would like to see in the Christmas-movie genre, and he replies that he’d love a holiday sci-fi movie. “Science fiction is a designer’s paradise,” he says, “because even a pen is special.” I ask if he goes all out decorating his own home for the holidays, and he says no before I can even finish the question, then excuses himself to marshal some more human-size nutcrackers from the lawn onto the veranda.

I chat with a set decorator named Michael Yori, who has worked with Wise and Hart on a number of films, during a brief moment of respite between hanging up decorations and taking them down. He talks about the business of Christmas as though it’s mercenary work, taking a long drag on his vape while he does, then adds with a thousand-yard stare, “This Christmas shit is steady.” It’s also hard-core. “Last year, I had a big cut on my arm, and it started to scab over but it scabbed over with glitter. It’s embedded in my flesh.”

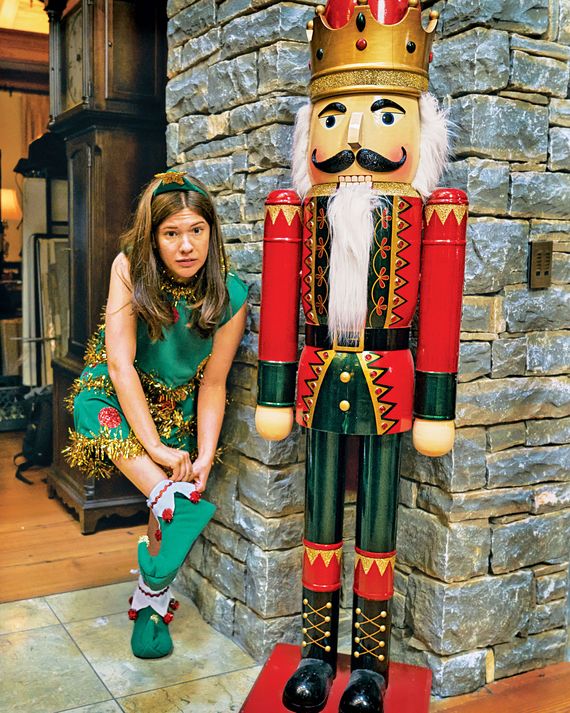

Day four is my last on set, and wardrobe has put me in a green dress with tinsel and baubles on it and a little conical headpiece with a star on top. In my most difficult acting challenge yet, I will be playing a Christmas tree in a scene in which the bootcampers are put to work throwing an ornament-decorating party for rowdy children. The dress is almost cute, more cosplay than vérité. The other background actors aren’t as lucky. Todd, who’s talking to the group about being the “world’s first cybersleuth,” is doing so in a reindeer onesie with a perky Bambi tail. Jenna’s in a snowman suit, and Jai, the tallest of the group, is naturally an elf. At lunch, I sit next to the head of the hair department, Monica, and I compliment her on Winokur’s sky-high tease and giant bows. They’re at the level of exaggeration I wish more of these movies would embrace. “It’s a running joke,” says Monica. “We start with a small bow and get progressively bigger and bigger over the course of the movie. It wasn’t in the script. It was my idea, and people went with it.”

After lunch, hordes of children swarm the set like lantern flies. They’re the nieces and nephews of crew members and friends of Hart’s son Tucker. The party we’re filming involves badly behaved children testing the patience of the bootcamp recruits. For the first time on set, I’m seeing tiny cracks in the snow globe. Tucker has a scene with love interest Aiden (dressed as Santa). The environment is overstimulating, even for someone with “child star” baked into his DNA, and Tucker can’t get his lines right. He grows hyper and restless, and Hart ends up bribing him with a Target toy-aisle visit to get through the scene. This approach seems as if it would work with actors of all ages. (Another person who is excellent with children? Rita Moreno, who ad-libs a version of “The Three Little Pigs” for a story-time scene while cracking the kids up by saying the word butt a lot.)

I notice an unfamiliar cameraman taking B-roll footage. It turns out he’s making a promotional video for the Tennessee Entertainment Commission to attract more moviemakers here. It’s clear why shoots like this one are good business for the state. I’ve seen the scale of this production, the number of film-industry workers it employs in the area, and the ancillary businesses that sprout up around it. The set decorator runs his own year-round Christmas store in Jonesborough. The young women who lead the wardrobe, hair-and-makeup, and art departments get to make bold creative decisions like letting Santa wear blue. These movies are training grounds for writers and steady work for production teams in smaller markets. It’s an efficient, chaos-free set. Well, except for the kids, one of whom saunters up to a background actor dressed as a reindeer posing on all fours and asks, “Are you finna get rode?” And with that, I’ve had enough Christmas for one August.

Murray later tells me he’s hopeful that he and others will keep finding new directions for the genre. “You don’t want to feel like you’re writing and creating sausages on the assembly line,” he says. “The last thing I ever want to do is be in the sausage-factory business. That’s the biggest challenge. Trying to write something that stands out from the bunch.” Even the unexpected casting of someone like Moreno suggests the humble TV Christmas movie is letting itself dream bigger. Murray tells me that other networks inspired by Lifetime’s success are getting into the business. Last year, his friend Danielle von Zerneck collaborated with Ana Gasteyer and Rachel Dratch on the Comedy Central original A Clüsterfünke Christmas. This year, Murray’s releasing an HGTV original Christmas comedy, Designing Christmas. “It in some ways resembles the Modern Family format or Abbott Elementary with addressing the camera,” he says. “It’s also a workplace movie.” Murray explains that he wants to expand the genre to make more stories about non-romantic love: Christmas movies about friends, colleagues, and chosen families. So maybe they’ll buy my screenplay; it’s a twist on the classic workaholic woman. This time, she’s a blogger who goes to a small southern town to write about a bootcamp for Santas and ends up learning the true meaning of Christmas. I’m thinking Marissa Jaret Winokur for the lead.