Thirty-three minutes into Malfunction: The Dressing Down of Janet Jackson, we see the incident, a moment that can easily be missed if you blink, sneeze, or look away from the screen for the teeniest of tiny moments. It is shown once, uncensored, by director Jodi Gomes, in a way that illustrates the truly minor nature of an episode that got blown up into a media controversy and a culture clash about decency.

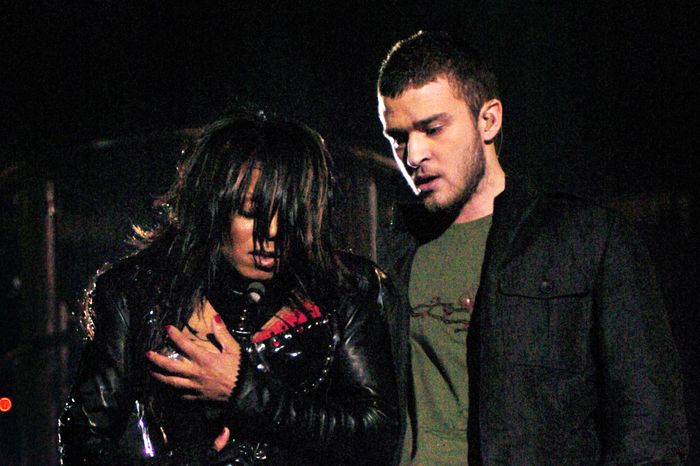

“It,” of course, is the tearing of Janet Jackson’s top during the Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime show, a move executed by guest performer Justin Timberlake, that accidentally exposed her bare breast to more than 144 million live television viewers. “We saw Janet’s nipple for nine-sixteenths of a second,” notes Touré, a cultural critic who used to write for Rolling Stone. That highly specific measurement sounds minuscule, yet the amount of time Jackson’s right breast was visible somehow seems even shorter than that. If you were watching the Super Bowl in real time in 2004, there is a solid chance you didn’t even notice it when it actually happened. But skittish network and NFL executives, conservative politicians, and overblown media coverage turned that “nothing” into a “wardrobe malfunction” wildfire, one that the latest documentary in The New York Times Presents series connects to a broader conversation about the unfair expectations surrounding women’s bodies and sexuality, as illustrated by the issues Janet Jackson has faced throughout her entire career.

The New York Times Presents, which debuts tonight at 10pm. ET on FX and tomorrow on Hulu, has covered numerous subjects, including COVID, Breonna Taylor’s death, and vaping. But its episodes about Britney Spears — Framing Britney Spears and Controlling Britney Spears — have generated the most attention and arguably played a role in the pop star’s conservatorship finally getting dissolved. Thematically, Malfunction is a continuation of the Britney installments; it’s about the public mistreatment of a major pop star, and what that says about the currents of misogyny that ran through American society in the ’00s — and often still do. One could also rightly describe it as another installment in The New York Times Presents sub-series, “Justin Timberlake, You’ve Got Some Explaining to Do.”

If you’re expecting to finally get a play-by-play on what happened that Super Bowl Sunday directly from Jackson or Timberlake, you won’t find that here. Neither appears in new interviews for this episode, although some key plot points from that night are provided by other parties, including former NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue, and Salli Frattini, former senior vice president for MTV, which produced the halftime show in 2004. What’s more illuminating, however, is the way this documentary connects the dots from so-called Nipplegate all the way back to the beginning of Jackson’s career.

Early in the show, footage of a very young Jackson appearing on The Merv Griffin Show with her brothers demonstrates the degree to which, even as a child, she was encouraged to lean into her sex appeal. “C’mere, lover boy,” she growls into a mic during a hip-swiveling performance that the audience clearly finds adorable.

Malfunction then cuts to Jackson’s roles on television — as Penny on Good Times and Charlene on Diff’rent Strokes — and an interview she did many years later with Anderson Cooper in which she describes being told by someone in wardrobe, on her first day on the Good Times set, that her chest had to be bandaged, presumably to flatten it. She would have been 11 years old at the time. The following season, she was told she needed to lose weight because she was too heavy. “I immediately thought, As I am isn’t good enough,” Jackson tells Cooper. Tito Jackson also confirms on-camera that when they were kids, her brothers nicknamed her “Donk,” or Donkey, a reference to her body supposedly being shaped like a donkey’s.

That Jackson was able to not only overcome all this, but embrace her sexuality later in her solo career is remarkable. But Malfunction reminds us that the older, sexier Jackson who appeared topless on the cover of Rolling Stone got pushback, too, for metaphorically removing the bandages she was once told she needed. “Our culture doesn’t know what to do with independent women, and definitely not independent Black women,” says Jenna Wortham, a writer for the Times. “And when there is an opportunity to punish her for it, they did.”

Providing all this background before delving into the actual Super Bowl performance makes that punishment seem all the more personal when it arrives. Malfunction naturally revisits the uproar unleashed in the wake of Americans being exposed to the sight of a woman’s breast for — again, I cannot stress this enough — nine-sixteenths of a second. Like everything in The New York Times Presents series, the evidence of the uproar is presented straightforwardly, letting its ridiculousness speak for itself.

“Janet lost her damn mind, whipping out her titty on a Sunday afternoon,” Chris Rock shouts in a bit from his Never Scared tour, adding “and a 40-year-old titty at that.” A clipping from a newspaper article refers to Janet Jackson as “a bitch in heat.” The New York Times doesn’t let itself off the hook, either, noting one of its own articles that said of the halftime show, “Perhaps the one moment of honesty in that coldly choreographed tableau was when the cup came off and out tumbled what looked like a normal middle-aged woman’s breast instead of an idealized Playboy bunny implant.”

So much of the shame and blame is directed at Jackson: for creating an alleged publicity stunt, for her age, for not seeming sufficiently penitent, and for the simple fact of her body, one that has been criticized since she first stepped in front of a camera. It is wild that everyone was so bothered by a boob and almost no one commented on the actually shocking aspect of that reveal: that a white man ripped off the clothes of a Black woman, who, based on her immediate reaction, was not expecting to bare as much as she did. The whole atmosphere after that Super Bowl is, still, shocking in its hurtfulness. A woman who was famous for being in control had it literally stripped away from her.

The atmosphere at that time also seems incredibly stupid — the FCC spent a lot of time and money investigating the incident, then fining CBS more than half a million dollars for it, a fee the Supreme Court ruled the network did not have to pay — and, in retrospect, overflows with hypocrisy even more than it already did. There is a lot of talk, from Tagliabue, from Jim Steeg, former head of the NFL special events department, and from football fans, about how the NFL is supposed to provide wholesome family entertainment. “To have sexualized the Super Bowl in the manner that they did it, is just unforgivable,” says a female talking head on an unidentified news program. You mean the Super Bowl that routinely shows provocative commercials, brought to you by an NFL that exploits its cheerleaders and lets the Washington Football Team basically do whatever it wants? You mean that Super Bowl and that NFL?

There are also rivers of irony in the fact that the then-head of CBS, Les Moonves — you know, the guy who had to resign in disgrace after accusations of sexual harassment — was so “offended” by Jackson’s routine that he suggested she should pay the FCC fines, and also demanded that both she and Timberlake apologize during the 2004 Grammys. Jackson refused to say sorry and skipped the ceremony that year; Timberlake did apologize and got to perform.

Timberlake comes across just terribly in Malfunction, thanks to footage that shows him almost bragging about getting nasty with Miss Jackson immediately after the performance, then later absolving himself from blame, and, much, much later, happily prancing across the Super Bowl stage in 2018, when he got to headline the halftime show. The documentary makes a point of reminding us of the backlash from Janet Jackson fans that rippled through social media on that more recent Super Bowl Sunday — the hashtag #JanetJacksonAppreciationDay became a thing — and of Jackson’s subsequent induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2020. While also noting Moonves’s fall from grace, the episode implies that, as a culture, we’ve become more fair and that we show greater respect toward women who proclaim their sexual agency

It’s nice to think so, and maybe some of that is true. But what rings in the ear most after watching Malfunction isn’t the sound of progress, it’s a warning in the form of something else that Wortham says: “We should never forget what they did to Janet. We should never forget that outrage.”