The zombie genre has been declared dead over and over again, only to keep rising (har har) but that doesn’t mean it hasn’t been done to death. This is probably my own personal failing, but whenever I hear about a new zombie-related cultural effort, my own eyes roll to the back of my head, I start letting out long, droning moans, and I awkwardly scamper away. Maybe I’m in a minority here. The genre retains its popularity (and even some of that metaphorical power George A. Romero brought to it back in the day), and has recently acquired a newfound topicality thanks to, well, you know. And to be fair, some promising recent efforts have managed to punctuate the undead’s undying force-field of cliché. The Korean TV series Kingdom, a period political drama about a zombie plague, was one refreshing effort, as was the 2016 Korean hit Train to Busan, which ingeniously crossbred the zombie flick with another unlikely subgenre: the runaway train thriller. There, the combination of high-speed, tick-tock claustrophobia and flesh-eating shenanigans wound the viewer so tight that even ridiculously familiar tropes suddenly felt revitalized.

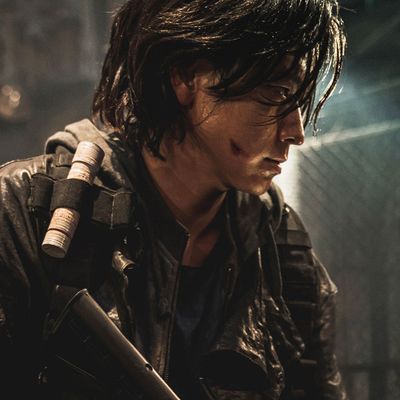

The new sequel, Train to Busan Presents: Peninsula (which actually opens in theaters this weekend, so you might want to make sure you’re not in the middle of your own plague vector before heading out to see it), starts off with a few similarly promising twists, but quickly unlearns all the lessons of its predecessor. There’s no train this time, but early on, there is a ship, filled with refugees from zombie-ravaged South Korea, which the film uses as the setting for an emotional prologue involving Jung-seok (Gang Dong-won), a military officer who is transporting his sister, her husband Chul-min (Kim Do-yoon), and her young son to safety. After a zombie breakout happens on the boat, the sister and her boy are sacrificed, in a scene that is equally terrifying and heartbreaking. This is the emotionally scarring memory that our heroes will have to work their way through, as the film jumps ahead four years. Jung-seok and Chul-min have since landed in Hong Kong, devastated and penniless and discriminated against, and there is still bad blood between the two: Chul-min blames Jung-seok for not doing enough to save his wife and his son. Their lives in ruins, the two men join a small crew sent by a local gangster back to the blasted Korean port of Incheon to retrieve a truck full of money. Okay. A zombie heist picture? That could be interesting.

Don’t get too excited. The money is treated as such an afterthought that to call it a MacGuffin would be an insult to lions in the Scottish highlands. Once Chul-min and Jung-seok return to Korea, director Yeon Sang-ho (who directed the original Train to Busan, so he knows what he’s doing, generally speaking) presents us with a frustratingly familiar dystopia. Jung-seok hooks up with a family that has been sheltering and surviving in this wasteland — and with whom he has some secret history. Chul-min finds himself in the clutches of a brutal militia whose bloodthirsty leader likes to pit his prisoners against hordes of zombies in grimy gladiatorial combat. There’s a decidedly Mad Max-ian flavor to this world, with nods to Beyond Thunderdome, The Road Warrior, and an epic, lengthy, elaborate multi-vehicle chase that feels inspired by Fury Road.

Alas, little of it registers as particularly new, or interesting. It might have worked had the film actually done anything meaningful with Chul-min and Jung-seok’s emotional distress and resentment. The film’s prologue is deeply moving, but we never quite get the sense that Jung-seok abandoned the child and his mother callously — this is, after all, a zombie movie, and once the kid was bitten, there was nothing to be done — which means that the central emotional dilemma remains unconvincing. That doesn’t have to be a problem; the bitterness and guilt between the brothers-in-law can exist even if the original betrayal was mostly imaginary. But instead of exploring it or complicating it, the film treats it as a given, then uses that trauma as shorthand for additional shading and motivation, which just means that everything else rings false, too.

If I’m harping an unusual amount on a momentary failing of character development, it’s because the film doesn’t give us much else to care about. The zombie sequences are strictly pro-forma; the undead are treated mostly as a nuisance rather than a genuine threat this time around, which is probably intentional. The car chases are debilitatingly fake-looking and try to make up for their flatness with speed, to little effect. It is my fervent belief that any movie cliché can be made new if the people living through it are otherwise compelling. It is also my fervent belief that if your sequences are ingenious or exciting enough, then you could get away with under-developed, maybe even bland characters. (Any Tron movie comes to mind.) Peninsula fails on both ends of that transaction. But maybe that’s just the zombie-cynic in me talking.

More Movie Reviews

- What If We Didn’t Know Abigail Was a Vampire Movie?

- David Dastmalchian Deserves to Be a Star

- Guy Ritchie Goes Brutally Posh