As summer turns to fall, the beach read finds itself replaced with another type of literary enjoyment. Now is the time to snuggle up with a book, perhaps under a blanket with a cup of apple cider, while the weather cools and the leaves change colors. Not every new book we’re excited about this autumn is cozy, though. There’s room on the bookshelf for gripping coming-of-age reflections, Japanese poetry, A-list autobiographies, historical fiction, and even a bit of frog dissection, so to speak. Let’s crack open the spine on Vulture’s 24 most anticipated books of fall 2023.

September

How do you sleep at night? French writer and longtime insomniac Marie Darrieussecq would like to know. Insomnia and writing “both thrive on the fantasy of the chosen,” she writes. A product of 20 years of sleep struggles, this strange but delightful book intertwines a diary of the author’s own restlessness with her collected evidence of the nighttime woes of other writers, including Proust, Duras, Kafka, and Césaire, and their pharmacological means to achieve rest. From a series of photos of the author’s hotel beds over the years to a spiraling account of the things that keep us up — ghosts, babies, trauma, a lack of shelter — this book examines a roving mind with the nocturnal logic of association and quiet. —Jasmine Vojdani

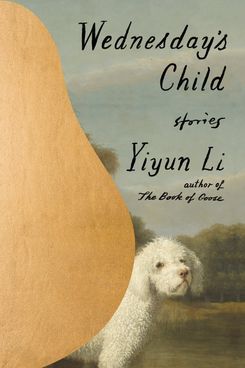

The Chinese-born writer who actively chose “to be orphaned” from her native language in favor of English, which she considers her “private language,” follows last year’s extraordinary The Book of Goose with a collection whose title is plucked from a nursery rhyme. Written over the course of a decade, these stories take up the author’s familiar themes of mourning, motherhood, and aging. In the titular story, a mother whose teen daughter appears to have killed herself travels alone during the pandemic and remarks that “there are very few things in life that are impervious to time’s erosion.” In “When We Were Happy We Had Other Names,” a bereaved mother compares a child’s death to “the probability of an ant’s being struck by lightning” and then having to “survive and toil on” before she attempts to use a spreadsheet to quantify a lifetime of loss. Few writers tackle the way grief reverberates through our lives with Li’s frankness, tact, and humor. —J.V.

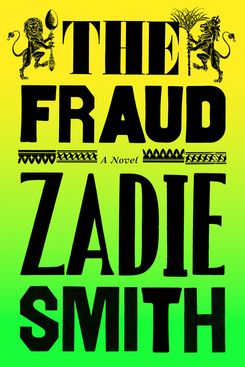

The celebrated author’s first novel since 2016’s Swing Time is a historical tale about class, writing, and gossip that begins with a famously controversial trial. In 1870s England, Eliza Touchet, the housekeeper and cousin to a middling novelist (who happens to be friends with Charles Dickens), becomes obsessed with the Tichborne case — a real-life court drama, relentlessly covered by London newspapers at the time, in which a poor man claimed to be the heir to a massive fortune who had supposedly died in a shipwreck. More than the suspected fraud himself, the abolitionist Eliza is captivated by the trial’s main witness: a man named Andrew Bogle who was enslaved for years on a plantation in Jamaica. —Emma Alpern

After Matrix, a sexy spin on medieval romance inspired by the 12th-century writings of Marie de France, Lauren Groff revisits her thesis: that much suffering comes from a misreading of Genesis, whereby man dominated the Earth in lieu of caring for it. Except this time she does it through a story described as a “female Robinson Crusoe,” following a servant girl who flees an early-American settlement in Jamestown, Virginia. As she navigates the harshness of nature and violent encounters with Indigenous people, we get flashes into what she’s left behind: her home, her language, and Bess, a child born into her care whom she considered her only family. A revelation about what exactly the girl had to do to escape the plague-infested colony comes at the end, but the flowing prose holds tension and sows mystery on every page. —J.V.

An extraordinary act of fan service for all of us who enjoy making literary jokes on the internet. The activist-author not only acknowledges the fact that she has often been confused with Naomi Wolf — the feminist author turned anti-vaxxer and conspiracy theorist — she has written a complicated, self-aware, and thought-provoking book about it, using her experience of being mistaken for the Other Naomi to explore how two paths can diverge so sharply. —Maris Kreizman

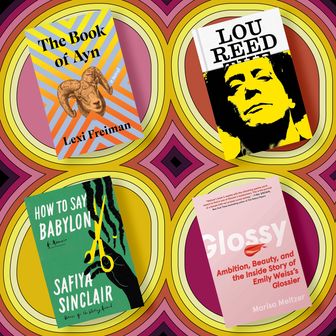

A reporter on the wellness and fashion beat with an ear for gossipy storytelling, and in the billion-dollar beauty brand Glossier, Marisa Meltzer has found a subject that suits her talents: Emily Weiss, Glossier’s secretive founder who once featured in a three-episode arc as a character on MTV reality show The Hills. This is the rare business book that’s actually fun to read. —M.K.

This book by the German writer is a kaleidoscopic romp through the decades that preceded World War II. The biography follows the lives and romances of the artists and thinkers who made a name for themselves during this era: from Simone de Beauvoir to Anaïs Nin to Bertolt Brecht. Through a series of vignettes, the work explores how these artists came to prominence and their affairs of both the body and mind — but hovering over it all is the impending catastrophe of war, which brings gravity to the book that balances nicely against its leaping, gossipy opening. As the culture of Europe shifts away from experimentation and play toward large-scale social collapse, the author wrestles with how easily — and disconcertingly — hate can take over a population. —Isle McElroy

The author has carved out a wildly productive 2023. In March, McKenzie Wark released Raving, her book about the underground queer and trans rave scene in New York. Now, her memoir about her childhood in Australia and transitioning later in life appears, written as a series of direct addresses to the women in her life, from mothers to lovers to herself, as she comes to terms with her gender identity. In an address to herself, Wark writes, “You — what do I even remember of you? Our past selves are probably extensively edited editions. Let me see what I can piece together.” The memoir is an attempt to make sense of the edited self and the person who we once were. A portrait of selfhood under construction. —I.M.

Zhang’s debut novel, How Much of These Hills Is Gold, was an epic reimagining of the western. Now she sets her sights on a dystopian future: In the aftermath of a global environmental disaster, a chef abandons her career in London to join an affluent mountaintop food-research community insulated from the problems plaguing the rest of the world. As she grows closer to her employer and his daughter, she rediscovers her passion for food, for others, and for herself — and learns that the community’s motives go far beyond preparing elaborate meals. An exploration of the kinds of complicated moral choices we are all likely to make as the planet becomes increasingly inhospitable. —I.M.

October

The release of a new collection by Lydia Davis will always be a big deal — she’s long been able to tell a whole, complicated story with just a sentence or two — but this one is especially exciting because you won’t be able to find it on Amazon. The author teamed up with the folks at Bookshop.org to publish it, the first book that the indie retail game-changer will put out as a publisher. Not only does Davis have the power to murder readers with just a few words; she’s giving life to indie bookstores. —M.K.

In her 2013 novel Hild, the author told the story of the teenage Hild of Whitby, an enigmatic figure from the rise of Christianity: In the seventh century, England was made up of small warring kingdoms. Hild, enlisted to be her king’s seer, cobbles together what seem like magic insights using her talent for social observation. That novel’s much-anticipated follow-up finds Hild a little older and living in a small stronghold of her own — while tensions across England are rising, threatening all sense of order. Like the first book, Menewood anchors its far-off subject matter with close attention to the natural world. It’s also visceral in a whole new way, dramatizing some of northern Britain’s most violent years. —E.A.

The musician Lou Reed is a slippery subject for a biography. He was notoriously prickly toward journalists, and his body of work actively resists interpretation. For this big new biography of the Velvet Underground front man, Will Hermes — longtime rock journalist and author of Love Goes to Buildings on Fire — threads the needle with a wealth of reporting, access to the entirety of the New York Public Library’s Reed archive, and a nuanced understanding of the man, who was less ahead of his time than apart from it. That description applies to both his music and his sexuality, which he didn’t care to define: “Reed lived as he pleased,” Hermes writes, “and answered to no one.” —E.A.

The author astounded me with When We Cease to Understand the World, a novel in which he explores the dark side of scientific breakthroughs by blurring fact and fiction in a way that might feel familiar to just about anyone consuming any form of media today. (It’s much easier to appreciate that blurred line when it’s done for the sake of art!) He promises to do the same with some of the early creators of AI in this novel, which will no doubt be equally as alarming yet also strangely beautiful. —M.K.

In this memoir, the poet reflects on her childhood in Jamaica living under the strict rules of her Rastafarian father, a volatile reggae musician who instituted draconian measures to protect his family from what he saw as the corruption of western influences. As a child, Safiya was able to find slivers of freedom and safety in the books her mother bought for her and her siblings, but her newfound independence resulted in clashes with her father, who became increasingly violent and paranoid as his daughter attempted to break free. Her book charts the unique ways she carved out a life while remaining true to the people and places she loves. —I.M.

Just over ten years ago, the author moved with her family from the U.S. to Rome to study Italian. The Pulitzer Prize winner has gone so far as to start writing in the language; her last two books were translated into English. Her newest is a short-story collection about Rome and its people — longtime residents, tourists, and immigrants. The characters here are mostly unnamed and near anonymous, many of them adrift after life-shaking relocations and trying to make their way in the massive city. In one memorable chapter, a flight of public stairs becomes the stage for a series of passing figures who race up them, sit on them, or “descend together like a bubbling hive.” —E.A.

On an antiquing trip through New England with his wife, a photography professor named Tunde notices two objects: an elegant antelope headdress made by the West African Bambara people and a photocopied note describing a Native American attack that took place in the 1700s. From there, Tunde’s thoughts spin out — to his teenage years in Nigeria (where parts of the book take place), the brutality of history, and the American “fever dream of mindless Indian violence.” Cole has written plenty of essays in recent years, many of them about photography; this is his first novel since 2011’s Open City, and it shares that book’s heady elliptical style. —E.A.

In this debut novel, Abernathy, a self-proclaimed loser, lands a job entering the minds of white-collar workers to remove anxieties from their subconscious. The gig seems like his big break, a way for him to escape mountains of debt and remake his life, possibly even find love. But it’s morally compromising, and he finds it increasingly difficult to separate work from life, dreams from reality. McGhee grapples skillfully with the complicated ethical questions at the core of late-stage capitalism. How much of yourself must you sacrifice in order to make a life? Who do we risk becoming in the pursuit of safety and comfort? —I.M.

Ward is a writer of skill and vision who has already won the National Book Award for Fiction for two novels in a row (Salvage the Bones in 2011 and Sing, Unburied, Sing in 2017). If only she had consistently been paid as such, but that’s another story. Her fourth novel is the story of an enslaved teenage girl who must walk the many miles from North Carolina to Louisiana when she is sold to a new owner. It promises to be a brutal read, but if there’s any author we can trust to take us on this harrowing journey and find beauty in the bleakest of human conditions, it’s Ward. —M.K.

November

Many excellent comedians (Maria Bamford, Aparna Nancherla, Gary Gulman, Leslie Jones) are putting out books this fall, and Vulture’s own Jesse David Fox is the critic who can put all of these power players into context, making an impassioned argument for why comedy matters and examining breakthroughs from the past 30 years to make the case for comedy as an art form that deserves to be analyzed and appreciated. Fox is funny in his own right, combining comprehensive knowledge with superfan enthusiasm. —M.K.

Ishii is one of Japan’s most celebrated poets. In this new collection, he continues his practice of modernizing the classical poetic form of the tanka, a five-line, 5-7-5-7-7 syllable poem that he instead writes in one line. His work is stark and sensuous: “Already my body is tired out with desire / Probably so is my soul,” he writes in “Bathhouse.” In “Treetop Flowers,” he captures the coy directness of desire: “All the flowers called flowers scatter / The naked mariner spreads the / Sails of his boat to the island of love.” Hiroaki Sato’s brilliant translation maintains Ishii’s innovations, including the poet’s nontraditional use of punctuation. This collection is an excellent introduction to the beauty of Ishii’s verse. —I.M.

When Park’s new novel was pitched to me as “Squid Game meets Gravity’s Rainbow,” suffice to say I was intrigued. Personal Days, Park’s 2008 office novel, is one of the best in that suddenly exploding mini-genre, and this next novel feels bigger and more ambitious and weird as hell. Same Bed Different Dreams is a multifaceted alt-history that traces the ripple effect of what might happen if the Korean Provisional Government had never been dissolved before the partition of North and South. Park has spent years as an editor in book and magazine publishing helping writers to make their own work better, so it’s thrilling to see what he can do now that he’s put on his author hat once again. —M.K.

Streisand is at the tippy top of a list of icons from whom fans have been clamoring for a memoir, and now the wait is almost over. Weighing in at a whopping 992 pages, My Name Is Barbra promises to be the perfect tome to gift for Hanukkah. Her publisher says Babs will discuss her trailblazing career in detail in the book, but here’s hoping she avoids a simple résumé rundown and spends many pages in juicier, more personal territory. —M.K.

Gabriel Bump, who won the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence for his debut, Everywhere You Don’t Belong, returns with a novel about a young Black couple who attempt to create a Black utopia in rural Massachusetts. After losing their only child, the pair comes to see the world as hostile; they are eager to live safely, to build a place where they can feel loved and seen for who they are. What begins as a fantasy soon becomes reality when a wealthy benefactor helps bankroll the community’s construction and outsiders begin to show up. But as the numbers accumulate, so do the concerns. No utopia can avoid conflict for long. —I.M.

Anna, a 39-year-old writer living in New York, has been canceled. A New York Times reviewer deemed her satirical novel about the opioid epidemic classist, and her publisher drops her, Twitter attacks her, and she’s suddenly overwhelmingly disliked. Full of despair but not at all remorseful, she finds herself ushered into a new world populated by belligerent centrists and edgelord podcast hosts. Most significantly, she discovers a group of Ayn Rand superfans and decides to devote herself to the infamous advocate for unfettered egoism. Anna’s newfound passion for objectivism takes her all the way to Hollywood — at least for a while, until she loses her grip on things again. Freiman’s novel (her second after 2018’s Inappropriation) is uncomfortably funny and sure to cause a stir. —E.A.

More From 2023 Preview

- The Search for the Next Will and Kate

- 25 New Classical Music Performances to Hear This Fall

- 10 Art Shows We Can’t Wait to See This Fall