When it comes to hip-hop, New York and New Jersey are in an entanglement. Their close proximity allows for easy cultural exchanges, with people migrating from one region to another, or artists looking to expand their fan bases by traveling to different locales in the tristate area for shows and networking. However, while New York has the historical distinction of being the birthplace of hip-hop, New Jersey’s influence on New York, and subsequently the entire culture, has to do with business.

When the late singer-songwriter Slyvia Robinson and her late husband, businessman Joseph Robinson Sr., founded Sugar Hill Records in 1979, in Englewood, New Jersey, they changed the trajectory of hip-hop. At the time just before Sugar Hill Records launched, rappers mostly stuck to performing in clubs like Harlem World and Disco Fever, in the Bronx, and at neighborhood block parties around the city. In a 2014 interview with DJ Vlad, Grandmaster Caz noted how very few people had managers, pre-Sugar Hill Records, counting Grandmaster Flash and the Funky 4 + 1 among the rare exceptions. So many of the moves and deals that shaped the cultural zeitgeist in hip-hop at the time were parlayed in person, where artists represented and advocated for themselves. However, Slyvia Robinson recognized that rap was fast becoming a viable art form and sped up the inevitable.

“What the MCs were doing then was just rapping over music. It was like a party thing. We used to go out to different clubs and that’s all they did. One time, my sister had a birthday party at Harlem World for my aunt Sylvia. She came there and started listening to how they were rapping over the music and made the decision to put it on wax,” remembers Donna Ward, Robinson’s niece and former promotions director for Sugar Hill Records. “That’s why she bought the three guys together.”

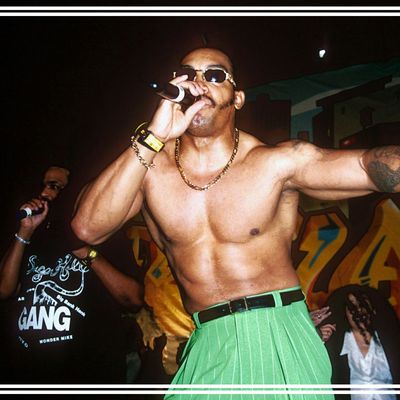

Sugarhill Gang started when Sylvia and Joe Robinson began asking men they encountered in various locations, sometimes on the street, if they could rap. The couple were told that they should check with Big Bank Hank, who worked at a local pizza shop at the time; he told them he could rap and auditioned on the spot. Wonder Mike went next, and then Master Gee, who happened to be walking by with a friend who coincidentally knew Sylvia, went next inside the Robinsons’ car. They began recording about a week later.

It wasn’t easy getting “Rapper’s Delight,” Sugarhill Gang’s monumental 1979 first single, on the radio. It wasn’t easy getting any songs on the radio, but at that time, the DJs who served as the gatekeepers at their respective stations, didn’t see it for rap songs, and found it absurd that Sugar Hill Records was trying to make the push. Ward, however, traveled the country, called around, and got as much face time as she could with as many DJs as possible. Her tenacity went a long way — so, admittedly, did some extra money. (“Let’s just say, there was a lot of payola going on then. It’s been so many years, so they’re not going to put me in jail now,” Ward jokes.)

Ward’s daughter, Shanell “Lady Luck” Jones, who was signed to Def Jam in the late ’90s, remembers her mother’s invaluable contributions well. “Aunt Sylvia had Sugar Hill Records, but my mom is the one who got the song hooked. She was the one who convinced them DJs to play a 15-minute rap record. It’s hard to convince them to play a three-minute record,” she says. “Uncle Joe sent her with the bag, and she went all around the country. I didn’t even realize who my mom was until I started working on a documentary [still in the research stage] about her. I put together a list of the DJs and radio stations that she was with, and I was amazed because this lady was really out here doing things.”

“Rapper’s Delight,” released in September 1979, became the first rap song on the radio, breaking on East St. Louis station WESL by a DJ named “Gentleman” Jim Gates. It eventually reached No. 37 on the Billboard Hot 100, sold over a million copies, and catapulted hip-hop into an international business. Sugarhill Gang have the distinction of rapping on the song that transformed hip-hop, however, they were met with criticism about where some of its lyrics came from. In that same interview with DJ Vlad, Grandmaster Caz mentioned that Big Bank Hank, who managed his group, the Mighty Force, was in a position to hear and memorize several of their lyrics. (He’d also worked at that pizzeria in New Jersey so that he could finance his group) Hank was at work one day when Sylvia Robinson walked in and asked him if he could rap. The rest, as they say, is history.

“There were people there who don’t feel good about [the rumors of lyric copying], but entering in from the surface level, it’s like, ‘Wow, this is amazing,’” says John Robinson (no relation to Sylvia and Joe), also known as Lil Sci of Scienz of Life, a New York and New Jersey–based group that became a staple in ’90s underground hip-hop. “But at the same time, it’s undeniable that even if you have some negative feelings around it, it did set the blueprint for the business.”

By the time Robinson — who was born in Harlem — established Sugar Hill Records, which took its name from Harlem’s famed Sugar Hill neighborhood, a creative hub for Black artists in the ’20s, she already had experience as a record producer, singer, and songwriter. She performed with the guitar and vocal duo Michek & Sylvia, known for 1956’s “Love Is Strange,” produced 1960’s “You Talk Too Much” (for which she was uncredited) for a New Orleans singer named Joe Jones, and did production on “It’s Gonna Work Out Fine” (uncredited), the 1961 hit that scored Ike & Tina their first Grammy nomination.

After the success — and criticism — of “Rapper’s Delight,” Robinson went on to sign acts that were considered more “authentic,” such as the Funky 4+1, the Sequence (which Angie Stone was apart of), the Treacherous Three, Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, and more over the next few years. Robinson co-wrote and produced several hit rap songs, including Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s 1982 classic “The Message,” another prolific tune that influenced generations of rappers who came up during the ’80s and ’90s.

“Sugar Hill Records is the reason why you still have hip-hop today,” says Ward. “It was the opening of record labels, and everyone getting into studios and making these songs.” The first iteration of Sugar Hill Records folded in the mid-’80s. By then, other labels had begun signing hip-hop acts, and Def Jam, a label solely dedicated to rappers in its beginning, was on the rise. Def Jam introduced the world to some of hip-hop’s most iconic songs and artists, from Run D.M.C., to LL Cool J, to Redman, an outlier who put Newark, New Jersey — a city forgotten in pop culture — back on the world’s radar.

“Living in Jersey, I knew glimpses of the riot era, and what was happening back in the ’60s and ’70s, but I didn’t realize how rich of a music history Newark had,” John Robinson admits. “And it made sense because some of the musicians that played here in New York live right across the water in Newark, which was once considered a jazz capital, and other places in Jersey.” He continues, “So Redman repping Newark, Brick City, stems from that cultural pride. New York gets all the props, but don’t get it twisted, the Bricks is just as thorough. That’s the foundation Redman was coming from. Newark, New Jersey, is entrenched in music history [and] Brick City is the first thing that comes to mind, if you ask someone that’s connected to the culture about New Jersey hip-hop, because of Redman.”

To date, the Garden State has produced some of the most impactful artists the world has ever known. DJ Cheese, from Plainfield, was the first non-New York–based turntablist to win the DJ Battle for World Supremacy at the New Music Seminar in 1984. East Orange’s Naughty by Nature, one of hip-hop’s biggest groups, released their first album in 1989 under the name New Style on Bon Ami records, a subsidiary of Sugar Hill Records. That album flopped, but they kept developing their craft and were eventually discovered by Queen Latifah and Shakim Compere of Flavor Unit Management in the early ’90s. From there, they went on to deliver some of hip-hop’s biggest anthems, like “OPP,” “Feel Me Flow,” and “Hip-Hop Hooray.” They won a Grammy for Best Rap Album for 1995’s Poverty’s Paradise. Meanwhile, Treach, the group’s leader, embodies what it means to be a rapper’s rapper — he figured out how to be pop but also appeal to the streets without being corny, influencing both Eminem and Jay-Z. In 1995, Lakim Shabazz, another late-’80s New Jersey hip-hop pioneer, founded the Flavor Unit Crew, a collective of New York and North New Jersey based rappers and DJs. Queen Latifah later came along and revitalized Flavor Unit in the ’90s, turning it into a management company. (Also hailing from New Jersey: Lords of the Underground, the Fugees, Poor Righteous Teachers, Ice-T, Rah Digga, Joe Budden, Akon, Fetty Wap, and dozens more.)

Both Robinson and Lady Luck credit theatrics and eccentricity as the hallmarks of NJ hip-hop: Redman merged lyricism with comedy, and set the tone for how to create epic skits; Naughty by Nature figured out how to authentically balance being hood but with pop appeal; the Fugees deftly genre-bended hip-hop, reggae, and soul, illustrating how singers and rappers collectively enhanced group sonics; and Queen Latifah brought business acumen, laying the groundwork for how rappers could become a brand that transcended rap and extended to Hollywood. There have been times when artists from New Jersey were needed on a track for their particular set of skills. Would Nas’s “If I Ruled the World” have inspired a generation of then-young millennials without Lauryn Hill’s vocals? Would EPMD’s “Head Banger” without Redman shouting, “Negroes!” at the beginning have the same level of raucous detail? Would the world have ever known a duo as iconic as Redman and Method Man had Def Jam never existed? Would Def Jam have existed without seeing the possibilities laid out by Sugar Hill Records?

“Sugar Hill Records stretched the creative mind towards entrepreneurialism. It allowed it to happen and be seen. I think that changes things forever,” John Robinson says. “It’s culturally responsive and aspirational — like, I see people who look like me running a record label in this business and pushing forward and things are happening. “Rapper’s Delight” is one of the most successful records. Despite all of the chitchat, the perspective was brilliant. The story was a brilliant family business pioneering a new sound, connected to culture and connected to community, and without that happening things would be different.”