Sheree Miller has pretty much given up on American television. The 50-year-old stay-at-home mom spends about six hours a day sitting in her living room in La Vernia, Texas, in front of a large TV that’s never turned on. Instead, she’s busy working on her laptop as a volunteer for Rakuten Viki, a streaming service that adds subtitles to entertainment produced primarily in Asian countries. For over a decade, Miller has been part of the global community of unpaid users who translate video content on Viki into more than 150 languages. Viki declined to share an exact number, but Miller estimates that there are hundreds of thousands of people participating in the system; the 2015 book The Informal Media Economy put the number at more than 100,000. For their efforts, top contributors get a free Viki subscription. That’s all the compensation Miller says she needs: “The platform itself is for volunteers — those of us in obsession mode.”

Before Viki, overseas fans who wanted to watch subtitled Asian TV shows or films found themselves playing monthslong games of roulette with piracy sites. “It was just horrible, the wait,” Miller recalls. “Sometimes dramas would never get finished, or a website would be obliterated, and then you’d have to go looking around, trying to scrounge up another website to find the same drama.” Viki was born in 2007 as ViiKii.net, a project by three college students at Harvard and Stanford. The site’s name combined the words “video” and “Wiki,” reflecting a desire to translate videos using crowdsourced contributions. The founders didn’t invent the concept of community-powered subtitling — before high-speed internet existed, anime fans were trading “fansubs” on VHS tapes and laserdiscs — but they weren’t shy about wanting Viki to eventually become, according to a blog by co-founder Jiwon Moon in 2008, a new “grand cultural Silk Road.” Viki developed software that allowed multiple people to subtitle a project simultaneously, and in 2013, three years after its official launch, the company was acquired by Japanese e-commerce giant Rakuten for $200 million.

Today, the site once funded by donations from early users like Miller now offers two tiers of paid subscriptions as well as a limited free plan with ads. Much of Viki’s popular content hails from South Korea, including K-dramas What’s Wrong With Secretary Kim and Descendants of the Sun, reality programs like Queendom 2 and Running Man, and annual awards shows for music and acting. The platform also hosts titles from mainland China, Taiwan, and Japan, among several other countries, and since 2015, it has produced its own Viki Originals, including the viral Chinese series Go Go Squid! Viki survived even as major streamers such as Netflix and Amazon bid up the costs of licensing Asian content, which Variety reported was the reason for Warner Bros.’s 2018 shutdown of DramaFever, once Viki’s biggest competitor. By the end of 2021, Viki was serving 53 million users — many of whom want their new subtitled content now.

“Viewers of every language have something in common: They bitch, they complain,” says Connie Meredith, an 80-year-old contributor based in Honolulu, Hawaii. On Viki, an episode of a popular drama is typically translated into English, Viki’s base language for subsequent translations, within 24 to 48 hours of airing. Meredith says volunteers have been able to finish English subtitles as quickly as two to three hours. But less popular shows or shows that have complex dialogue take longer to be completed, and secondary language teams have to wait their turn for the English version. If you scroll through the ratings of any given title on Viki, you’ll see that the worst reviews overwhelmingly reference subtitling speed rather than the actual quality of the show or movie. Did the French translators go on vacation or what? Why am I paying for Viki if the Portuguese subtitles are never done on time? Meredith says reviewers frequently point out when translations are available on other sites before Viki. “And I’m thinking, Sure, you can get it with mistakes,” she says. “We are not in a race.”

In a sense, though, they are. The competition for international programming is only getting fiercer in the streaming-verse — and if Viki’s users aren’t getting the content they want at a speed they deem sufficient, they may look elsewhere. Yet Viki’s strategies to ratchet up subtitle production haven’t always sat well with an unpaid volunteer workforce that has wondered at times what, and who, the company actually values. “In experimenting to see what worked and what didn’t,” says Mariliam Semidey, 37, who served as Viki’s senior manager of customer and community experience from July 2016 to June 2021, “we might’ve made some mistakes.”

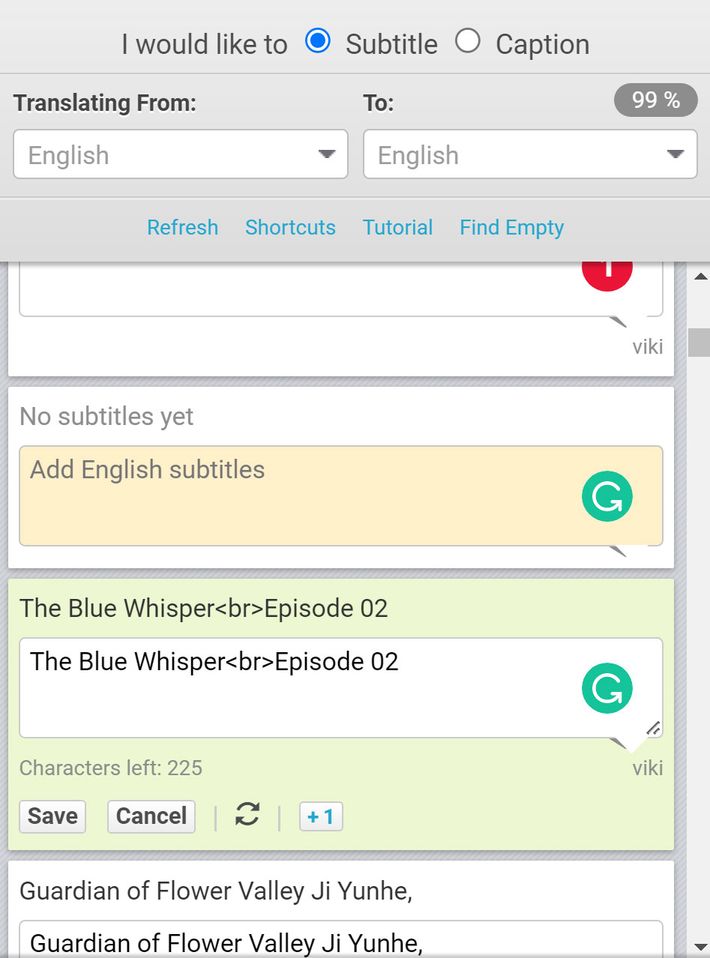

Time and time again while Semidey worked there, the question came up during corporate meetings: Should Viki get rid of its volunteers? But management always ultimately agreed that those contributors were too valuable because of the quality of their work. Over the years, Viki’s volunteers have developed their own training programs and standards for capturing cultural references, obscure idioms, and other tricky linguistic nuances. Their self-managed system involves several roles that don’t require fluency in multiple languages, although translation experience is also not necessary to become a subtitler. As a volunteer team lead, Meredith accepts subtitlers who do at least “a halfway decent job” on a short translation test she created. “The rule is don’t guess. If you don’t know the whole thing, skip it, and somebody else will fill it in,” says Meredith, who has taken Korean language courses through the University of Hawaii to improve her vocabulary. She might spend two hours hunting down a specific slang word or reaching out to friends with Ph.D.’s to determine the exact meaning of a phrase. Those efforts are representative of an ethos among the volunteers that has been present since the beginning: the understanding that good translations require time, effort, and teamwork.

“I think a lot of devoted volunteers feel the same way I do,” Meredith adds, “that we wouldn’t be here if it was a paid job because they can’t pay us enough for the time we spend.”

That’s why tension creeps in when volunteers get pushed to complete their contributions faster. Semidey says that when she was at Viki, any hour-long episode that volunteers took longer than eight hours to complete was considered “late” based on the speed of other streaming sites. If a team displayed a pattern of being too slow with their subtitles, Viki would speak up. Miller gets frustrated when Viki staffers reach out to tell her that volunteers should be moving faster. “Most of the people I know who contribute to Viki are not stay-at-home moms,” she says. “They have full-time jobs as nurses and techs and all kinds of things.” There are forms of compensation for contributors, starting with a free subscription to Viki, which is earned when a volunteer finishes 3,000 subtitles or segments (roughly equivalent to seven or eight episodes of work). From there, incentives are given to subtitlers who reach 20,000 contributions, rank high on Viki’s contribution leaderboard, or win volunteer-organized contests — in the past, such rewards have included tote bags, signed Psy CDs, and a Roku 3. Miller sees these perks as nice gestures of recognition. But as long as there’s no payment, it doesn’t sit right with her “to say to somebody that has a full-time job, ‘You better get your heinie here and sub this today at so-and-so time.’”

The dynamic Miller describes has contributed to the controversial efforts Viki has made to increase translation output over the years. In 2018, according to Semidey, Viki began using paid translators to speed up progress on select titles that weren’t expected to be popular, though Semidey says that the company sometimes made incorrect predictions and brought them in on shows that volunteers wanted for themselves. Nonetheless, she says, the decision resulted in a 50 to 60 percent decrease in customer complaints, though volunteers feel that it comes at the cost of quality: Often the subtitles they leave for last, such as the lyrics of official soundtracks (OSTs), require the most intricate translation work. “It’s like the difficulty of subtitling poetry,” says Meredith, who spearheaded the movement to start subbing OSTs on Viki in the first place. She estimates that the overwhelming majority of lines from paid translators “are wrongly subbed,” compelling volunteers to go back and make corrections.

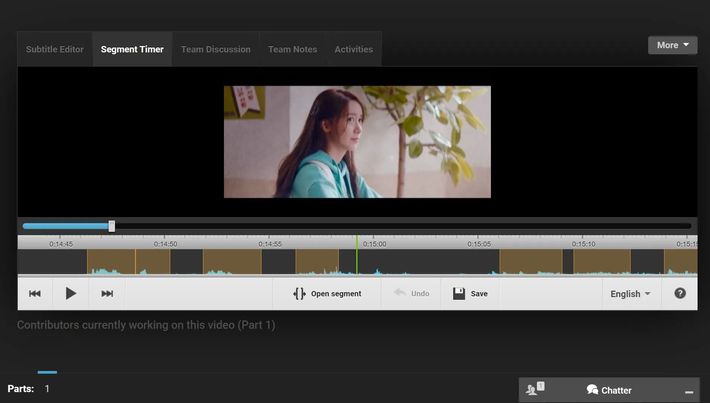

The same goes for content that arrives on Viki with premade segments and subtitles. Beverley Johnson Wong, a 64-year-old contributor based in the Twin Cities, says it takes “at least double or triple the time” to correct errors compared to doing the work from scratch. She specializes in segmenting, which involves cutting videos into the clips that subtitlers fill in. Redoing short segments that cause text to disappear too quickly is tedious and doesn’t count toward contributions for Viki’s leaderboard, yet segmenters still clean up the mistakes. “We don’t want people thinking that was our work,” she explains, “because it was not done well.”

Volunteer frustrations hit a flash point in September 2019, when Viki introduced a robot into its workforce. That month, hundreds of Viki volunteers went on strike because of the rollout of “Vikibot,” a collaborative project with the Rakuten Institute of Technology that used machine learning to automatically create segments and suggest subtitles. A form of AI called natural language processing also allowed it to learn from Viki’s large library of volunteer translations. The bot had already been implemented on inactive titles for a couple years, but Semidey says it was fed incorrect data and began overwriting existing subtitles in several languages. Outraged volunteers who felt that the machine’s work was subpar translated a strike notice into 12 languages. On Viki’s discussion board, one disgruntled user pointed out the site’s own ban on volunteers using automatic translation tools such as Google Translate: “Can I report Viki if they don’t follow the own guidelines they set?” Another warned, “Remember that we are the reason why Viki exists today as it is.”

Roughly a week later, Viki’s community team held a call to issue an apology and assure volunteers that future use of machine translation would be “as minimal as possible.” But the trust was broken, says Semidey. When Viki proposed a feature the following year that would allow viewers to opt to switch to a separate track of “auto-translated” subtitles, volunteers reacted negatively, stating that the decision would pressure them to rush to prevent viewers from settling for lower-quality translations. While the auto-subs feature was not officially implemented, current volunteers still identify external translations from paid translators and auto-subs as a persistent issue.

Semidey says that working at Viki was a constant struggle to balance the needs of volunteers with the wishes of customers who could threaten to cancel subscriptions. During her time at the company, she remembers having at most three staff members assigned to directly interact with its vast network of volunteers. She also saw several well-known contributors quit over conflicts with Viki staff or other volunteers. When she left in 2021, she felt there were many promises Viki failed to deliver on, including better project-management tools.

“We understand that there are elements that can be improved within our Viki Contributor community, which is why we value their thorough and honest feedback,” Viki said in a statement from current community manager Sean Smith, noting that the company has “enhanced” project management and user-messaging features over time. “We’re actively engaged with a mixture of contributors to further improve tools and workflows.”

Meanwhile, Viki’s overall contributor numbers continue to grow. During the pandemic, volunteers had more free time to join Viki’s pool, leading to 22 percent year-over-year growth in subtitlers globally from 2020 to 2021, according to company data. In 2021, the average monthly contribution by Viki’s community of active subtitlers and segmenters increased by nearly 40 percent. Manuela Ogar Mraovic, who is currently topping the May community leaderboard, had only been subtitling on Viki for a couple months before taking the top spot in March. The retiree from Šibenik, Croatia, hasn’t dropped below second place since, and says she’s “really enjoying every second in this community, working and gaining knowledge.”

Some longtime contributors nevertheless have concerns about the platform’s sustainability, especially as Asian entertainment continues to gain international popularity and attract investment from large corporations like Netflix, Disney+, and Amazon Prime that don’t rely on volunteer-powered systems. One anonymous volunteer who was involved in the 2019 strike says they believe Viki’s volunteer community will inevitably “disappear” in the long term, noting that machine translation software is said to be improving in several key languages. “But we have dozens and dozens of other languages on Viki. That’s why they need us,” the volunteer adds. “For now, we are useful because we are better qualified in all the languages of the world.”