Richard Belzer died in February. We weren’t friends but were friendly; I was more a fan than anything else. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, I saw him perform many times. “The Belz” became a legend not because he got old and nobody knew what else to say about him but because he did legendary things: He hosted shows at New York City’s hottest showcase club, Catch a Rising Star; worked as the first-ever warm-up comic for Saturday Night Live; and opened for Warren Zevon on his infamous Excitable Boy tour in 1978.

Zevon’s tour was the first time I saw Richard: walking onto a Washington, D.C., stage with no guitar in hand to face thousands of raucous fans who had paid to see a rock concert by the “built a cage with her bones” guy. By then, I had been doing stand-up for a little over a year and was as surprised as everyone else to see a comic onstage. The difference was I was excited when he launched into a stand-up act — the people around me, not so much. The boos and angry shouts immediately peppered the air.

Comedy-club audiences very much want the comic to win against hecklers, while rock fans are just as likely to cheer for the heckler to chase this unknown party crasher off the stage. I watched as Richard gamely tried to get into material but was forced to battle hecklers during his entire set. I remember only one line: “Hey, pal, how about I come down there and do a dick dance on your tonsils?” Watching him play whack-a-heckler for his entire set was a lesson. He was cool in his delivery and precise with his words, never showing fear or anger. He exited with the same strut he entered with and to more applause than jeers. He never gave up the stage.

When he actually got to do his act in clubs, Richard had all the tools: a quick mind, an ear for impressions and dialects, a decent singing voice, and a fearless attitude. But what made the room fill with comics was his crowd work. His attitude was so New York — and not a “Woody Allen, Central Park carriage ride, Annie Hall” kind of New York but the “Martin Scorsese, rain-soaked garbage strike, Taxi Driver” New York. He put such anxiety in the room, way more than the usual “Hope this comic can make us laugh” nervousness.

During any given show, he might talk to ten audience members and insult each one in a different way. By the time he finished mauling some heckler, the rest of the audience avoided his gaze like he was a gang of switchblade-flicking, leather-jacketed hoodlums entering their empty subway car at three in the morning. His New York speaking rhythm pulsed with New York phrases: “Yeah, right.” “What’re you gonna do?” “You know what I’m saying?” Sometimes that last one was a slam, and other times it was an admission he was on his own: “You know what I’m saying? … Apparently not.”

In an era when most comics worked clean to get on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, Richard used fuck in all its forms. The Port Authority should have hired him to record greetings at bus terminals, train stations, and airports: “Welcome to New York, you fucks. Have a good fucking time — but don’t blame me if you get fucked up. You know what the fuck I’m saying?” He had nicknames for the audience: “kid,” “pal,” “babe,” and his signature, “Sparky.” Once he tagged an audience member “Sparky,” they might as well have started playing taps.

I loved whenever a tourist in the Catch audience would finally snap and shout, “You talk too fast!” Richard would whip back, “You listen too slow, pal!” and resume his high-speed delivery. Another favorite was him dismissing a drunk: “Why don’t you go outside and practice falling down?” Within the context of his freewheeling style, even a stock line sounded off the top of his head. It seemed every night Richard would lean down to a ringsider and ask, “Hey, pal, can I bum a cigarette? I left mine in the machine.” He would take a drag of the cigarette, exhale, then say, “Anybody can quit smoking. It takes a real man to face cancer.” He would spin off a smoking or heckler exchange into a related bit, making the standard part of his act look improvisational to the audience. That was another great lesson from Richard: The more material you produce, the greater the chance that any exchange with the audience can lead you into a proven piece of material. Of course, when watching someone as talented as him wade into a crowd, there were lessons, and then there was the unteachable.

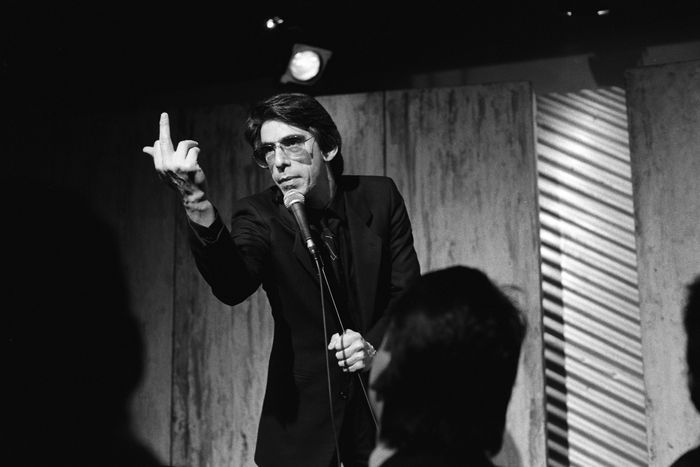

Richard didn’t just go after hecklers who confronted him. He went after the table talkers, bathroom walkers, and pretty much any movement that caught his predator’s gaze. It didn’t take much to set off his hair-trigger lip. Maybe that contentious relationship with the audience was installed in his comedic DNA from the physical abuse of his childhood; no doubt his upbringing contributed to his strong anti-authoritarian attitude. Even his tinted glasses formed a subtle barrier between performer and audience: I’m up here, and you’re down there, and let’s not play that it is anything else. The audience can easily be viewed as an authority figure: As comedians, we don’t just seek audience approval in the form of laughter — we need it. But Richard seemed to rule the stage without any of that need. I was so mindlessly pursuing it like a dog chasing a car without a thought to what I would do with it. Richard’s “Take me or leave” attitude seemed to eschew the need for laughter, and as a result, it earned him a ton of it.

Richard was admired and respected by so many of us, a true comic’s comic. But that crown can be crushing. Outrage was not the marketing tool and brand it’s become today, but it made Richard a legend while still in his 30s and broke. He could not get to where he wanted to go on the attack, no matter how artful his annihilations. I had heard he grew tired of watching lesser comics swim like dolphins while he was fighting the undertow. Whatever the reason, the Belz made a strategic shift in his 1986 HBO special, Richard Belzer in Concert, and decided to play nice. His crowd work was easygoing, even friendly. He showed vulnerability and a need to connect with material about his abusive childhood and a violent encounter with an idiotic Hulk Hogan. Richard still wore the tinted glasses for the benign crowd work, but they came off for the rest of the performance. He even dropped his standard black suit, white shirt, and tie for a sweater. (The Belz in a sweater!)

A year later, Richard and I were hired by a D.C. FM rock station to prepare the audience for the coming of Howard Stern, his third radio market. Richard and I did some area gigs together. One show was in a big bar one exit too far from the city. Nice guy Richard stayed in the limo because it was the Belz who took the stage in full attack mode. It really was an improvisational work of art, a comedic Jackson Pollock using audience blood. My high-school friend in attendance remembered it as “viciously funny.” You can put a sweater on a tiger, but sooner than later, somebody’s likely to get mauled.