Almost 30 years ago, not long after the collapse of the Soviet communist empire, Sesame Workshop — the company that produces Sesame Street — hired me to create Ulitsa Sezam, an original Russian adaptation of Sesame Street. For the next four years, I had the privilege of collaborating with hundreds of talented artists, writers, musicians, filmmakers, actors, puppeteers, and media professionals in Moscow as well as Sesame Street’s brilliant veteran creatives and researchers of the U.S. show.

I had first come to Russia in the early 1980s as an American exchange student to study Russian in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). For the next decade, I stayed in the land of my ancestors (my grandfather left Belorussia in 1912), producing television news for CBS, ABC, and NBC and directing and producing PBS documentaries. I made serious films about economics, underground culture, and politics, traveling from Moscow to Siberia and to Ukraine, Estonia, and Armenia. Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine I would later be producing a children’s comedy show. It seemed like a dream job.

However, I quickly discovered that despite my linguistic and cultural fluency of Russia, I had grossly underestimated the challenges the Muppets would face in Moscow. It turned out that translating Sesame Street’s ebullient and idealistic outlook to Mother Russia was not only incredibly difficult, but also incredibly dangerous.

As the executive producer of Ulitsa Sezam, I was thrown into the surreal landscape of Moscow television where bombings, murders, and political unrest constantly seeped into the TV studio where we worked. During our production, several heads of Russian television — our close collaborators and prospective broadcast partners — were assassinated one after another, and one was nearly killed in a car bombing. And the day that Russian soldiers bearing AK-47s pushed into our production office and sealed our office shut for good — confiscating our show scripts, set drawings, equipment, and even our adored life-size mascot — I thought it was “game over.” It wasn’t only violence that continually jeopardized our production but also cultural clashes pitting Sesame Street’s progressive values against 300 years of Russian Thought.

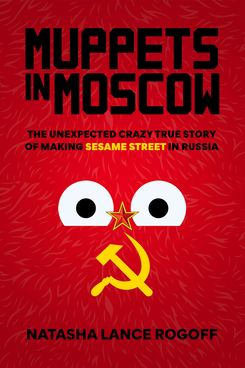

This excerpt from my new book, Muppets in Moscow: The Unexpected Crazy True Story of Making Sesame Street in Russia, is an account of the curriculum workshop for Russian Sesame Street, held in June of 1995 when educators from the former USSR assembled with the show’s research and creative teams from both sides of the Atlantic to determine the content of Ulitsa Sezam: what children in post-Soviet society would need to learn to thrive in their more open and democratic societies. The debates that emerged about education, history, individualism, inclusivity, and equality offer a window into the cultural discord and conflict between East and West that continues to dominate relations today.

While many American friends and my husband urged me during the course of the production to leave Moscow — especially when I became pregnant with our first child — I never could. There was something about Russia, about the brilliant people I was working with and the hope we all shared about the ways in which Sesame Street might change Russia for the better — encouraging freedom and tolerance and creating new opportunities for millions of children across the former Soviet Union. In hindsight, it’s a remarkable story and heartbreaking to think where we are today.

EXCERPT FROM ‘MUPPETS IN MANHATTAN: THE UNEXPECTED CRAZY TRUE STORY OF MAKING SESAME STREET IN MOSCOW’

The cornerstone of Sesame Street’s international television production model is the curriculum workshop, which involves bringing child education experts together with TV professionals to develop specific educational goals that also reflect the culture and values in the countries where new shows are being produced.

On the first day of the curriculum workshop for Ulitsa Sezam (Sesame Street in Russia), Moscow is experiencing a record-smashing heatwave for mid-June. I meet my production team outside the Danilov Monastery where the workshop will take place. The monastery, a fortress on the banks of the Moscow River, surrounded by freshly painted white stone walls, serves as the headquarters of the Russian Orthodox Church as had done, dating back to the thirteenth century.

The guards at the entrance wave us through to an interior courtyard where blue onion-domed churches with golden spires rise spectacularly from the ground as in a pop-up fairytale. Our motley crew shuffles past wilting flower beds while our eyes lock on monks in black robes pacing the gardens with pensive expressions. I watch them, imagining how much they must be sweating beneath their heavy robes.

The group proceeds in silence to the Monastery Hotel, the site of our workshop. After climbing four flights (the elevator is broken), we arrive breathless and sweating at a cramped conference room where I discover there’s no air conditioning. The temperature in the room must already be well over a hundred degrees.

“We’ll roast like chickens,” someone shouts in Russian from the back of the room.

To prepare for the curriculum workshop during the past months, Dr. Genina made several trips to far regions of the former Soviet Union, recruiting experts to help shape the educational framework for the show. On one occasion, Dr. Charlotte Cole (Chary), Sesame Street’s American director of international research, joined her in Ekaterinburg. Together, they interviewed Russian teachers and academics specializing in early childhood development. Dr. Genina told these educators that the goal of the curriculum workshop is to find a middle ground between Western liberal values, typical of the Sesame Street brand, and post-soviet Russian culture and spiritual values.

Dr. Genina expects a large group to attend the workshop, including members of Ulitsa Sezam’s and America’s Sesame Street research teams, and key members of my production team.

I feel fortunate to have gotten to know Dr. Genina better during the New York training held at Sesame Street’s headquarters some two months earlier. After graduating with high honors from Moscow’s Pedagogical University, she’d worked for twelve years at the Moscow State Academic Children’s Musical Theater. Her background in both education and theater impressed me, as did her commitment and tireless efforts improving the lives of Russian children.

Many of the educators had arrived the night before and are now gathered around the amenities table getting coffee and meeting each other for the first time. Dr. Genina moves through the crowd, enthusiastically greeting the forty-three participants. Some of the teachers and academics recognize each other while others, visiting Moscow for the first time, stand uncomfortably off to the side, shyly eyeing their colleagues.

Dr. Genina, smartly dressed in a lime green jacket, powder blue dress skirt, and sensible walking shoes, is making all feel welcome — and I expect her poise and diplomacy will be needed over the next few days. From across the room, she nods to me and smiles slightly. She’s the ideal facilitator for today’s discussion.

She looks nervous, as though steeling herself for the upcoming battles.

I see Misha already seated at the conference table. The first Playboy just hit Russian newsstands, and he’s discreetly reading it inside the fold of one of the binders that has been placed in front of each chair. Other members of my team politely engage with the academics, inquiring where they are from. Despite earlier objections to attending the seminar — not only because of money issues — they now seem to welcome the hiatus from our grueling fourteen-hour workdays producing the show. The free coffee also helps.

Chary arrives. She’s one of Sesame Street’s rising stars and a brilliant American researcher with a Ph.D. in children’s education from Harvard. Tall, bookish, and intense, she works unimaginably hard, traveling extensively and often to dangerous locations for Sesame Workshop. Dr. Genina announces the start of the meeting, inviting participants to sit along one side of four rectangular folding tables that form a square, with a space in the center. She explains the workshop will be conducted in Russian with translators interpreting for English speakers. Excitedly, the participants pick up the pens and plush Elmo and Cookie Monster dolls placed at each seating for them to take home.

“This is so professional,” one academic says, in Russian, as he picks up the pen, examining it and clicking the top before straightening the placard with his name in front of his seat. He screws the cap off the water bottle and takes a swig, nodding approvingly. The labels on the glass water bottles say Svyatoi Istochnik (Holy Springs), and in tiny Russian print, “Manufactured by the Russian Orthodox Church.” I laugh out loud. It’s incredible that the Orthodox Church runs a bottling plant. It’s a good business. Most Russians consider bottled water a luxury and this blessed water is more precious than most.

After initial introductions and a review of the agenda by Dr. Genina, we watch a video of the American show’s segments. Even before the subtitled clip of Cookie Monster is over, one of the participants, a mathematics professor, raises his hand, impatient to speak.

“Our preschoolers are much smarter than American children,” he says. “We will need a more advanced curriculum for our show.”

The educators on each side of him nod in agreement.

I sit quietly, aware how such a statement will sound to every American in the room. Education is one of the Soviet Union’s most outstanding achievements, but it’s not as though the kids have finished calculus by kindergarten.

But most of the Russian experts appear to agree with the math professor. To an assemblage of bobbing heads, a history teacher adds, “We must figure out how we will speak about our country’s difficult past and how to present it in a positive light so that we can restore faith in our country for future generations.”

A music expert suggests focusing on Russian culture as a way to “bring to light Russia’s glorious past — showing our music, our literature, and our faith.” His poetic words evoke beaming smiles.

Then the math teacher stands up, slaps his hand loudly on the table, and says, “We must remember that above all, we are still a superpower, and our children must not feel humiliation about our past. On the contrary, they must be proud of their country!”

Dr. Genina allows this free-form discussion, encouraging others who had not yet spoken to do so, but also reminds them, “It’s true that we are a superpower and that our children excel at learning letters and numbers compared to children in other countries, but they also need new skills and a new way of thinking to prepare them for a successful transition to a democratic society.” She emphasizes that the curriculum goals for Ulitsa Sezam will naturally differ from the U.S. show, but “not because Russian children are smarter.”

The educators speak at length, uninterrupted, and I sense they feel respected and valued. Dr. Genina emphasizes that while the Russian show is expected to be distinctly Russian, Sesame Street’s experience will be useful in helping the group develop concrete ideas for their show.

Dr. Genina halts the first session at eleven o’clock for a break.

Thank goodness. I need coffee after a morning listening to so many comments bashing American education.

Sipping my coffee in a corner of the room, I overhear a Russian physicist apologizing to Chary in English, explaining that he’s considering leaving soon. “You are tasking us with developing this curriculum to help kids learn the skills they need for an open society, but how can we do it if we haven’t lived in an open society?” There’s sadness in his voice.

I move closer.

Chary gently touches his shoulder, encouraging him to stay and engage in the multiday process and see what happens. He does.

Later in the morning, we broach the thorny topic of teaching children the skills needed to thrive in Russia’s new free-market society.

The physicist talks about how capitalism cannot meet the needs of ordinary Russian people who are used to socialist state protection and security. “Those who are less capable or weaker should not be penalized just because they don’t know how to make money. It’s not humane, and we shouldn’t teach such ideas to children.”

The health expert agrees, “We do not want our children to envy people who have material things and are rich.”

A preschool teacher with brown hair disagrees, “Ulitsa Sezam must include lessons about the free market. Otherwise, our children will not know how to survive.”

Across the table, one history expert exclaims, “Business should not be a bad word in Russian. We need to teach our children to respect people who are doing business because they are a creative part of the new society.”

The antipathy toward capitalism that some educators express is understandable. Most Russians are suffering economically, and no one disputes that inequality in Russia has risen, far surpassing levels experienced under communism. Russian life expectancy has plummeted, along with teachers’ lifetime savings, including many in this room. It’s not surprising they are frightened.

The math teacher shouts across the chasm between the tables, “Russia’s strengths are in math and science, and above all else, we must preserve this strength. We must not succumb to the West’s destructive obsession with capital.”

Another teacher argues, “If the show focuses on money in any way, our children will grow up paying attention to making money, instead of focusing on being socially responsible people.”

The group’s concern about how wealth will change their society is valid. Many of my Western friends in Moscow, and possibly even me, are guilty of evangelizing free markets while ignoring escalating economic inequality across the former Soviet Union. As I listen to the intense exchanges, I find it startling how many of these ideas about capitalism resonate with ongoing debates in America, between liberals on the left and neoconservatives on the right.

Natalia, a psychologist, raises her hand. Her voice is sweet and sincere.

“But our children already know all about money. Three-year-olds in my preschool class can tell me the ruble-to-dollar exchange rate even though it changes practically every day.” She pleads, “We can’t just ignore it. If we don’t help them understand what a free market is, our children will be left behind.”

These educators face a significant dilemma; few of them even know what a free market actually is. Three years earlier, these teachers were standing in front of their classes, waving wooden batons, conducting their pupils in songs glorifying socialism.

Raising my hand, I propose that Ulitsa Sezam could feature, for example, a segment showing children running a lemonade stand as a way of teaching about business and teamwork.

The group is horrified — not only by the idea of children selling items on the street but also at the thought of showing children engaged in what one participant calls “dirty mercantile activities.” “Only desperate, poor people sell stuff on the street to survive and it’s dangerous,” one educator argues. Another admonishes, “It’s not right to show children trying to earn money — it encourages individual greed.” I hadn’t anticipated my example would provoke such reactions. Of course, though, it makes sense — in Soviet times, selling items on the street was illegal, and only the poorest Russians or Mafia resorted to street commerce.

Skillfully changing the subject, Dr. Genina tells the group how Ulitsa Sezam’s research team canvassed teachers, librarians, and heads of nursery schools and orphanages in several regions of Russia for their opinions on what preschoolers should learn. “We were startled to discover that many Russian educators are unsure about the ideals and history they should teach children.”

For example, she says, one of the teachers interviewed said, “Thousands of children’s textbooks glorifying the Russian Revolution and its leaders had to be discarded, and there are no new books for us to use to teach children.”

In this stifling room, it’s hard to keep everyone focused, but Dr. Genina has the group’s rapt attention and presses on.

The next speaker is Dr. Elena Lenskaya, the head of the international relations department at the ministry of education. She’s well known among the other educators. Three years earlier, at Sesame Workshop’s request, she’d traveled to Washington, DC, to advocate for Russian Sesame Street before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee [chaired by then-Senator Biden].

She stands up to speak. “The Russian education system is certainly in a state of crisis,” she says. “We at the ministry do not have enough money to pay teachers’ salaries, let alone create new textbooks.”

Her voice softens, and Dr. Lenskaya addresses the elephant in the room: “The Soviet education system was set up to excel in science and mathematics, and we accomplished this beautifully. But today our education system is no longer tenable, and Ulitsa Sezam can help us by giving us an alternative tool to help educate our children while we redesign our curriculum for a new Russia.”

Many shift uncomfortably in their seats. They seem embarrassed to hear a government official acknowledge any weakness in Russia’s education system in front of the American guests. Dr. Genina offers a gentle statement of support, “All countries go through difficult times and being able to admit weakness is the first step to changing things.”

I feel grateful to Dr. Lenskaya and Dr. Genina for framing Ulitsa Sezam in a positive light. Although I’d anticipated some criticism of Sesame Street because our program is foreign, I’d hoped the Russian educators would recognize the artistic brilliance and universal humanity of the Muppets and understand the show’s potential value for their country.

Although I’ve been having discussions like these with my team for months, the penetrating insights raised on this first day of the seminar impress us all. I now realize why Sesame Street’s research-production model and the curriculum workshop are essential to the production process. The workshop is key to reaching a consensus on how to meet the actual needs of children and produce content that is relatable, relevant, and compelling. Despite this, the attendees appear immobilized by their differences, and I worry they will not come to a consensus. Chary assures me that she’s seen it before and encourages me to be patient.

By the end of the workshop, a consensus was reached, and production of

Ulitsa Sezam, which would run for four seasons, began.

Excerpted from the book Muppets in Moscow: The Unexpected Crazy True Story of Making Sesame Street in Russia by Natasha Lance Rogoff. Used by permission of the publisher Rowman & Littlefield. All rights reserved.

Natasha Lance Rogoff is the former executive producer and codirector of Sesame Street in Russia. She produces documentaries and children’s programming and is a fellow of the Art, Film and Visual Studies department at Harvard University