Children are inherently tacky. Left to their own devices, their preferred attire would mix the pomp of Liberace with the frouf of the Elizabethans. The more flammable the material, the higher likelihood they want to wear it: Dick and Jane favor poly blends. Kids rhapsodize about bug-eyed dolls with raspy mini boom boxes inside them, light-up teapots that giggle out tinny tunes. Kids’ taste can’t be trusted because they don’t have taste. They have preferences. For lamé.

The rest of us, though, live in fear of tackiness. It’s consumption that looks like consumption, camp without self-awareness. The specter of tackiness haunts our aesthetic attempts as the physical embodiment of trying too hard — the cardinal sin of ironized 21st-century social interaction. If minimalism is hyperconscious hyperselectivity, tacky is clueless excess, conveniently available at any price point. In her definitive “Notes on ‘Camp,’” about tacky’s sentient cousin, Susan Sontag wrote, “It’s embarrassing to be solemn and treatise-like about Camp. One runs the risk of having, oneself, produced a very inferior piece of Camp.” Which makes me wonder if there’s room for sincerity about tackiness. Would a “Notes on ‘Tacky’”-style essay bounce right off the leopard and pleather and rebound on the writer? Is it worth pinning down exactly what tacky is when its essence is to laugh in the face of neatness or order?

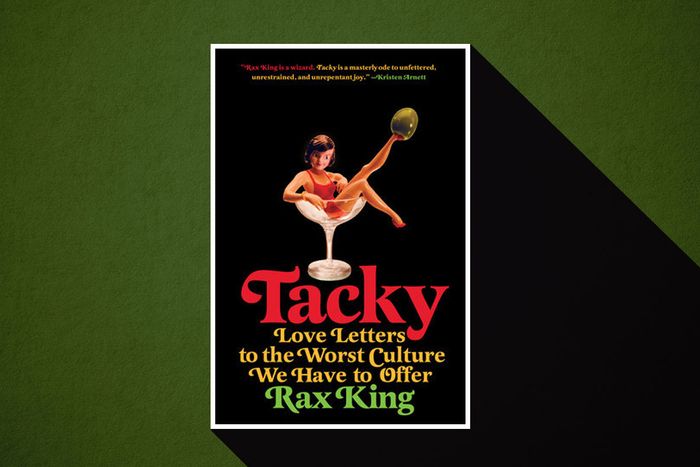

In her first essay collection, Tacky: Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer, Rax King decides to skirt the question, writing: “I still don’t really know what [tacky] means, though like Supreme Court Justice Stewart once said of the threshold for obscenity, I know it when I see it.” King, who’s based in Brooklyn and hosts the podcast Low Culture Boil, claims she never outgrew her unabashed childhood love for too much. In the book’s 14 dishy, memoirish essays, she hopes to convince us of just how wonderful it can feel to ingest aesthetic trash — if we could just let go of our snobbish inclination to enjoy it ironically, if at all. “I’m merely making explicit what most of us prefer to keep under wraps,” she writes, “which is that I like many things in this world, not all of which have the approval of n+1 or Artforum.” It’s a manifesto of anti-snobbery, equally vehement about corny TV, cheap perfume, and Flavortown. (King’s 2019 essay “Love, Peace, and Taco Grease: How I Left My Abusive Husband and Found Guy Fieri” was nominated for a James Beard Award.) This is a stance I can get behind, with Sontag’s endorsement: “One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.”

To King, tacky is in its own sparkly orbit, one swirl in the galaxy of plain old lowbrow or cheap. Her preferred subjects are nostalgia-driven, mostly stuff she loved as a tween and teen living in and around Washington, D.C., well before the age of discernment kicked in: Bath & Body Works’ “Warm Vanilla Sugar” scent, America’s Next Top Model, and other touchpoints of late ’90s and aughts American masscult. The writer — who asserts her down-market bona fides as someone who “dated an adult man who called himself Viper and believed that showers were a conspiracy inherited from the Nazi government” — equates “tacky” with “rebellious,” a label for bad girls with soft spots.

King’s writing in this collection often feels impetuous and unpolished. Her sentences (“Season one, episode one of Jersey Shore contains more action per second than either of the two world wars”) embrace a kind of hyperbole reminiscent of the early aughts internet and its provocations against formality — a subject I wish King had written about. That tone is perfectly on pitch for essays about Degrassi and Hot Topic. It doesn’t work as well when she’s stretching her own thesis. King ties her own sexual liberation to her tackiness, by which she means a healthy disregard for other people’s opinions about her bawdy sexts and ravenous appetite for screwing. “I had never minded being called a slut,” she writes. “It struck me as a toothless word — why should I be insulted by the correct idea that I was having sex?”

An essay about going to the mall as a high schooler is also about whether or not the two guys working at Starbucks and Mrs. Fields, respectively, wanted to fuck her. (They did, to a point.) Another, about the irreducible Samantha Jones of Sex and the City, is about the lackluster sex that accompanied King’s kink phase. For King, the freedom to enjoy tackiness seems to go hand in hand with the freedom to be a slut and enjoy it. But much of the book is about habits of consumption, and when King includes blowjobs and threesomes in that, the connection isn’t always clear. Sex shops sell tacky crap — and horniness might push us to buy it — but can a sex act itself be tacky?

I’m delighted that King hasn’t grown out of her adoration for calorie-rich, nutrient-lite culture. It was heavenly to be reminded of my own late ’90s mall wanderings. But I do wish Tacky cared about what tacky really is. When King writes about how Cinnabon-laden American malls were first imagined as “something analogous to the Viennese Ringstrasse,” or when she’s calling fans of the band Creed “flyover people, country idiots, anybody too buffoonish to know better” (a group in which she includes herself), she is only briefly glancing at the central tension of tackiness: the whiff of class confusion that trails behind it.

Picture Donald Trump’s New York penthouse, a caricature of a rich person’s home: The ice floes of marble, the hysterical gilding, the crowded crystals, all painfully opulent, oozing excess out of every light switch and doorknob. Think of the Real Housewives’ daily beauty maintenance, the way they bleach and contour and stiletto themselves until every inch of their photographable selves is designed to shoot dollar signs into the air. Dictators and despots drape themselves in ermine and hang up big game heads on their walls because excessive wealth evinces excessive power, or at least they think so. The rest of us laugh with a bitter taste in our mouths: What a dopey waste of millions. But this kind of tackiness is hardly marginalized. Arguably, it runs the world.

This is not what King writes about. She’s more interested in the tackiness of the American 99 percent, for whom the sin is an uncomfortable-to-behold mix of cultural cluelessness and misguided aspiration. She recognizes that tackiness is about longing. In her essay on the Cheesecake Factory — one of the collection’s most persuasive chapters — King notes that the megachain restaurant doesn’t seem to know that it’s just a place people pop into on a mall run when they want some heavily doused fettuccine alfredo. “The design principle of the place is courtesy of the Cheesecake Factory’s founder, David Overton, who refers to his distinctive blending of casual and ornate as stemming from the ‘palate of the common man,’” she writes. “As far as he’s concerned, the common man loves fall-of-Rome opulence, Penthouse porno lighting, and heaping plates of unpredictable food.” Though she sometimes digs beneath her pet topics to understand why they’re so scorned, she does seem to forget — or purposefully ignore — that “the worst culture we have to offer” slides up and down the spectrum of wealth, that the most blatant offenders are the heiresses with engagement rings so expensive they need faux versions to wear in public.

Lurking under any consideration of tackiness is the way that noting it in other people confirms our own superiority. You can spot it on the street or on TV or among the gifts a cousin leaves under the Christmas tree and think, I would know not to choose that. It’s a method of self-reassurance. Recently, though, the internet’s undying thirst for material has churned up a new type of nostalgia that resuscitates the imperfect remnants of cultures past. Reclamation is the order of the day, whether that means celebrating C-grade ’90s movies or the Delia’s catalog, and King is far from the only critic doing it. Some of King’s subjects, like Creed and Guy Fieri, have been so roundly abused that there’s no juice left in that lemon — in fact, Fieri’s reputation has rounded the corner, despite the occasional whiff of scandal around his empire.

That’s what’s so provocative about tackiness as an idea: Tacky status is temporary, but its possibility is eternal. King is devoted to it as a mantra with a full-body love for vigorously enjoying bad shit without any “protective layers of irony.” Beyond personal philosophy, she sees tackiness as a bonding mechanism. Writing about America’s Next Top Model, she celebrates the intimacy of tween and teen BFFs, bound by “femininity’s peculiar witchcraft” of physical transformation. In one essay, King writes about the college winter break she spent holed up with her ailing dad, eating corned beef on rye as together they immersed themselves in Jersey Shore.

When King first stumbled upon her father enmeshed in the lives of Snooki and JWoww, she writes, his house in Rockville, Maryland, “smelled like a wet ashtray. Empty shopping bags and cigarette cartons littered the floor.” He was wearing a “grubby gray tracksuit” and had essentially given up on improving his poor health and failing lungs. Luckily, hanging out with the guidos and guidettes doesn’t tend to make you contemplate your mortality or reexamine past relationship failures. Soon King and her dad slip into a viewing routine; eventually, they buy matching T-shirts with the show’s catchphrase, “Gym-Tan-Laundry,” and wear them, King says, without irony. King knew that leaning into Jersey Shore with her father, she writes, was “being summoned to launch into chaos with him.” She also knows it’s not really the show itself that they love; it’s the opportunity to float together in its mindlessness, an easy meeting place for their crumbling little family. For a supposedly tacky person, she is awfully self-aware.