I’d never noticed the curiously melancholy overtones of Harold Faltermeyer’s famous Top Gun theme until the opening moments of the brand-new Top Gun: Maverick. Maybe it was the distance in time. Back in 1986, those gongs and synth chords felt like a fairly standard New Wave–y intro; today, they register as a mournful dirge. Even the ensuing guitar riffs, which once seemed so triumphantly badass, now have a sad echo to them.

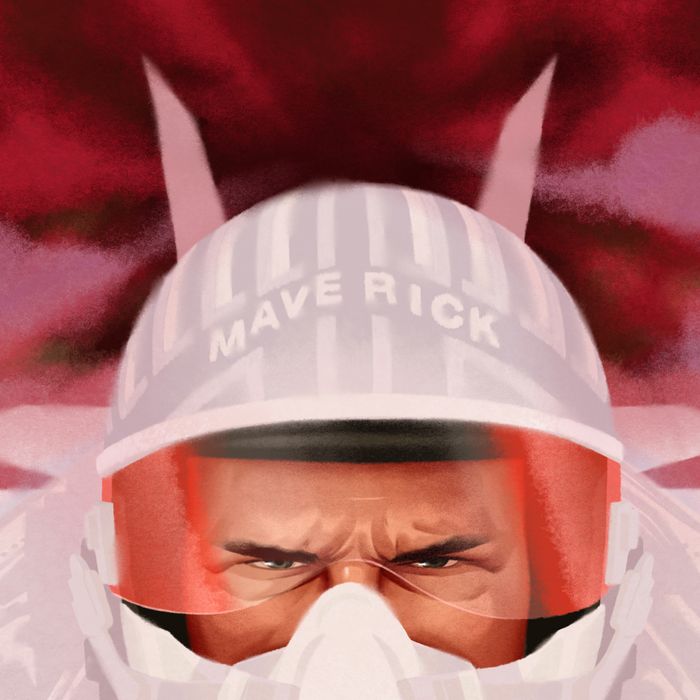

What’s even weirder: Maverick appears to recognize this. The sequel, directed by Joseph Kosinski, begins pretty much exactly as the first picture did, with a modified version of Faltermeyer’s theme playing against onscreen text introducing us to the elite training program for the Navy’s best pilots. That theme is then replaced (as it was in the earlier film) by Kenny Loggins’s power-pop classic “Danger Zone” as we cut to a montage of fighter jets launching off and landing on an aircraft carrier.

In the original Top Gun, directed by Tony Scott, this montage served a narrative purpose: It set up a scene involving Tom Cruise’s young fighter pilot, Maverick, flipping off an enemy MiG in the skies over the Indian Ocean. It’s a moment that encapsulates the whole movie. Yes, the Cold War was raging and some were upset about the film’s militarism, but Top Gun was really about the need for speed and being the best of the best, beach volleyball and Goose and “Take My Breath Away.” Most of all, it was about Tom Cruise and the unforeseen astronomical event that was his smile.

This time, however, the sequence fades to black with one last longing look at the ship, as if it were a lost Edenic dream. It reads as a eulogy for Maverick and, by extension, Cruise himself. As the screen slowly goes dark, you can feel in your bones the 35-plus years that have elapsed since that first film. Because for all its stunning flying sequences — mad ballets of soaring, spinning, spiraling, seesawing fighter jets — Maverick is a movie haunted by the image of its own star and of an America that may not exist anymore. Maverick moves through the film like a messenger from a dying world. As someone tells him early on, “The future is coming, and you’re not in it.”

In his heyday, Cruise was a youthful blank slate, a perpetual son for an era that always felt like it was promising new beginnings. After the actor agreed to make the original Top Gun, he and a team of writers worked to polish the script, adding a missing-in-action, larger-than-life father to Maverick’s psychological portfolio — a specter that would then proceed to reappear, in some form or another, in subsequent Cruise films. Maverick wore the daddy issues lightly; surely, amid the plot points one remembers from Top Gun, the story of the hero’s father is rather low on the list. Still, it helped make the character just vulnerable enough that an entire generation seemed to view itself in Cruise’s shadow: Women adored him, and men defined themselves in relation to him. (If you want an inexact comparison, consider what happened to Leonardo DiCaprio’s persona with Titanic.)

It would’ve been a no-brainer to have made a sequel to Top Gun right after it became the biggest movie of 1986. But back then sequels still had a whiff of vulgarity to them, and Cruise wasn’t interested — he wanted to prove his chops as a serious actor, and he would take on projects such as The Color of Money, Rain Man, and Born on the Fourth of July over the next few years. It wasn’t until several films into the Mission: Impossible franchise that the actor began even to entertain the idea of a Top Gun sequel; Cruise, Scott, and producer Jerry Bruckheimer had their first meeting about a follow-up in 2010.

By that point, it may well have been a matter of survival. After years as Hollywood’s most bankable movie star, Cruise had come close to flaming out completely, partly thanks to concerns over his heavy-duty involvement in Scientology, not to mention a series of bizarre television appearances (including an infamous Oprah Winfrey Show episode). His films were regularly underperforming. Female viewers, once a reliable demographic, turned on him. Even his longtime studio, Paramount, dropped him, citing his less-than-stellar public image (though he has continued to make Mission: Impossible movies, and now Top Gun: Maverick, with the studio). Perhaps not coincidentally, Hollywood was also losing interest in the kind of star-driven vehicles that had helped build Cruise’s career in favor of franchise pictures.

So he changed too: Of the 11 films Cruise has made since 2010, all but three are either sequels or movies that at least attempted to set up sequels. For some years, Mission: Impossible entries have been his only reliable moneymakers. Through them, Cruise has clawed his way back to respectability. And he has done so in an oddly poetic way: by suffering onscreen. He’s become known for those films’ spectacular stunts, many of which he conceives of and performs himself. Once Hollywood’s “It” boy — bright, gleaming, untouchable — Cruise fought back into our good graces by bleeding for us.

In so doing, he has somehow turned himself into a representative of a kind of old-school, let’s-do-it-for-real action-filmmaking that, for all its silliness, offers a refreshing alternative to the increasingly bland, overelaborate spectacle of Marvel movies and their ilk. Maverick subtly nods to all this with an early standoff between Maverick and a drone-happy general played by Ed Harris as well as constant reminders that the success of the central mission will depend on the people flying the planes and not on the technology itself. And, of course, much of Maverick was shot in real fighter jets with real actors enduring real g-forces on their faces and bodies. The level of authenticity achieved is, quite frankly, astonishing.

Cruise’s best performances were always extensions of his driven, all-American go-getter persona — the persona the original Top Gun helped create. This new Maverick has his daredevil temptations, to be sure, and when he’s flying — seen in close-up in the cockpit, his face yanked back by g-forces and his laser-focused eyes seemingly staring straight at us — he is brilliant and aggressive. On the ground, however, he displays a strange hesitancy, a fearfulness hiding behind that ever-present smile. A touching reunion between him and his former nemesis, Iceman (Val Kilmer), now the admiral of the Pacific Fleet and one of Maverick’s few remaining friends, feels like a confessional. As detailed in last year’s excellent documentary Val, Kilmer has lost much of his voice owing to a bout with throat cancer, so Iceman types his dialogue on a computer. As a result, for most of this affecting scene, Maverick’s is the only voice in the room, underlining the character’s loneliness. Even Cruise’s remarkably well-preserved face and physique add to his out-of-time and out-of-place aura. The actor has never seemed so vulnerable; Maverick might be the first time he has played a genuinely broken man, and there’s a poignant irony to the fact that he’s doing so while resurrecting his most iconic character. His tears, when they come, reach beyond the screen — they seem like a cathartic lament for everything that has changed since 1986.

All the death-defying feats Cruise himself has done in other movies linger in the background of Maverick, in which our hero seems constantly poised on the edge of death. Dialogue continually hints at the possibility, maybe even the probability, of his demise. (“Someone’s not coming back from this”; “This will be your last post, Captain”; “The end is inevitable, Maverick. Your kind is headed for extinction.”) The film follows Maverick as he trains a group of young pilots for an insanely intricate and deadly mission behind enemy lines, and we’re reminded, over and over, that some of these fresh-faced men and women won’t be coming back. The heavy aircraft canopies that close around them when they enter their planes look eerily like coffin lids. Even the flyers’ jargon for the cockpit — “the box” — is morbid.

Among those young pilots is Goose’s son, nicknamed Rooster (Miles Teller), who has some history with Maverick: Our hero is still guilt-ridden over Goose’s death and doesn’t want Rooster there, because he doesn’t want to be responsible for his. Rooster, eager to fly like his old man, blames Maverick for holding him back from advancing in the Navy, and maybe even blames him for the death of his father. Teller, whose achingly doleful performance in Kosinski’s 2017 firefighting drama Only the Brave was the heart and soul of that film, brings a contemptuous edge to Rooster that convincingly cuts Maverick, and perhaps by extension, Cruise, down to size.

As Maverick becomes more and more invested in Rooster’s and the other aviators’ survival, his own fate feels like it’s in question. Late in the film, right before the final mission, when he shows up to see Penny (Jennifer Connelly), a bar owner and admiral’s daughter with whom he has rekindled an old romance, he’s wearing his crisp Navy whites and looks like an apparition. It’s a teary good-bye, the kind we’ve seen countless times in movies about the military, but the grieving expression on Connelly’s face suggests that Maverick is already a ghost. A mood of sorrow hangs over the entire film, enhanced not just by the desperate circumstances of the narrative but also by its star’s newfound fragility. It certainly seems like it might be Maverick’s time to go.

Maverick is enormously entertaining, but watching it makes for a surprisingly emotional experience. That’s partly due to what happens onscreen, but a lot of it has to do with the memories the film evokes — memories not just of the first movie but of everything that has happened to the world, and to us as viewers, since then. If Cruise was the sign under which my generation came of age, then what to say about the fact that America has changed even more than he has? The original Top Gun distinguished itself through an authenticity brought to it by unprecedented technical support from the U.S. military, support the film paid back with its success: Top Gun was reportedly such a boon for recruitment that representatives for the Armed Services started setting up shop at theaters. But for all the flak it caught for its militarism, Top Gun’s jingoistic message was more latent than overt. The villains were rarely seen and never actually named. (Of course, any 13-year-old boy in 1986 could have told you that a MiG was a Soviet aircraft.) Superpower conflict was sublimated into Maverick and Iceman’s race to be the best pilot in their graduating class.

This time around, the enemy once again remains unnamed and unseen. It’s not the Soviets, that’s for sure. Rather, we’re told, it’s a rogue nation that is trying to enrich uranium. But it also happens to possess fifth-generation aircraft superior to anything in the U.S. arsenal. In other words, it’s an impossible enemy, almost as if in acknowledgement that a modern-day blockbuster can’t really afford to name any real adversaries. (That’s presumably why so many of them are about fighting aliens from other dimensions.) In 1986, for all the sword-rattling of the Reagan years (and the invasion of Grenada, and the bombing of Libya, and the meddling in Central America, and …), the U.S. had not been involved in a major armed conflict for some time. In the wake of the forever wars, however, that veil has been lifted, and the viewer’s relationship to the idea of combat has changed considerably. Gone is the image of the happy warrior, replaced by the grim spectacle of drone warfare, and street battles, and insurgencies, and long, agonizing, bloody stalemates. Military fantasies of the kind the first Top Gun sold have become largely extinct on our screens.

Which is maybe why Maverick takes place in such an otherworldly environment. The reality these pilots inhabit is a curiously empty one, mostly devoid of civilians, and the vast stretches of flat desert across which their jets blast feel like a dreamscape — an effect enhanced by the fact that during their training exercises, the valleys and mountains and missiles and enemy fighters they must evade exist only as readouts on computer screens. This is supposedly the same “Fightertown, USA” in San Diego where the first Top Gun took place (the airplane sequences were shot in real military-controlled areas where the U.S. Navy trains its pilots because those are the only places in the country where fighter jets are allowed to fly that low). But this time, the whole film seems to be playing out on the far edges of the empire. Never have fighters zooming across the screen looked so thrilling and felt so resoundingly, so gorgeously sad. This is also the universe in which Kosinski best operates. He finds cinematic poetry in liminal spaces — be it the melancholy, nocturnal digital netherworld of Tron: Legacy, or the flat futuristic wastelands in his moody sci-fi thriller Oblivion, or the great cathedrals of fire in Only the Brave.

He finds a similar poetry here, and it’s a profoundly moving one because the image of America from the original Top Gun still haunts the empty spaces of the new movie. The long-ago world that Maverick evokes and laments — the long-ago world of Cruise’s unblemished youth and of an influential era of pop filmmaking — also includes a happy national fantasy of freedom and certainty and goodness. Top Gun: Maverick isn’t unaware of this. The film isn’t political in any overt sense, but its hermetically sealed world suggests it knows it exists outside the margins of reality. Maverick makes quick references to Bosnia and Iraq but also notes that in a world where pilots are primarily called on to drop bombs or missiles from many miles away, dogfighting has become a lost art — one the movie will, of course, resurrect for one last ride, one last impossible mission against one last impossible adversary, threading the thinnest of threads through the tiniest of needles. The whole movie might be Cruise’s greatest stunt yet. Top Gun: Maverick is, finally, about the very impossibility of its own existence. The movie is its own ghost.

Top Gun: Maverick is in theaters May 24.