Editor’s note: New York’s issue of September 8, 1975 included a cover story about two gynecologist twin brothers who had died under strange circumstances on the Upper East Side. The brothers’ story eventually inspired a novel, Twins, by Bari Wood and Jack Geasland, and a film adaptation, Dead Ringers, directed by David Cronenberg and starring Jeremy Irons in both roles. In April 2023, Dead Ringers was remade as a Prime Video TV series, this time with Rachel Weisz as the doctors.

Like so many other people I spoke with this summer, I found myself uncharacteristically haunted by the deaths of Stewart and Cyril Marcus, the twin gynecologists found gaunt and already partially decayed in their East 63rd Street apartment amidst a litter of garbage and pharmaceuticals. The story of their deaths had, for me, even in its barest bones, that element of stupefying reality that Philip Roth calls an “embarrassment” to the writer’s imagination; here was a reality that could make the capabilities of even the most imaginative writer seem meager.

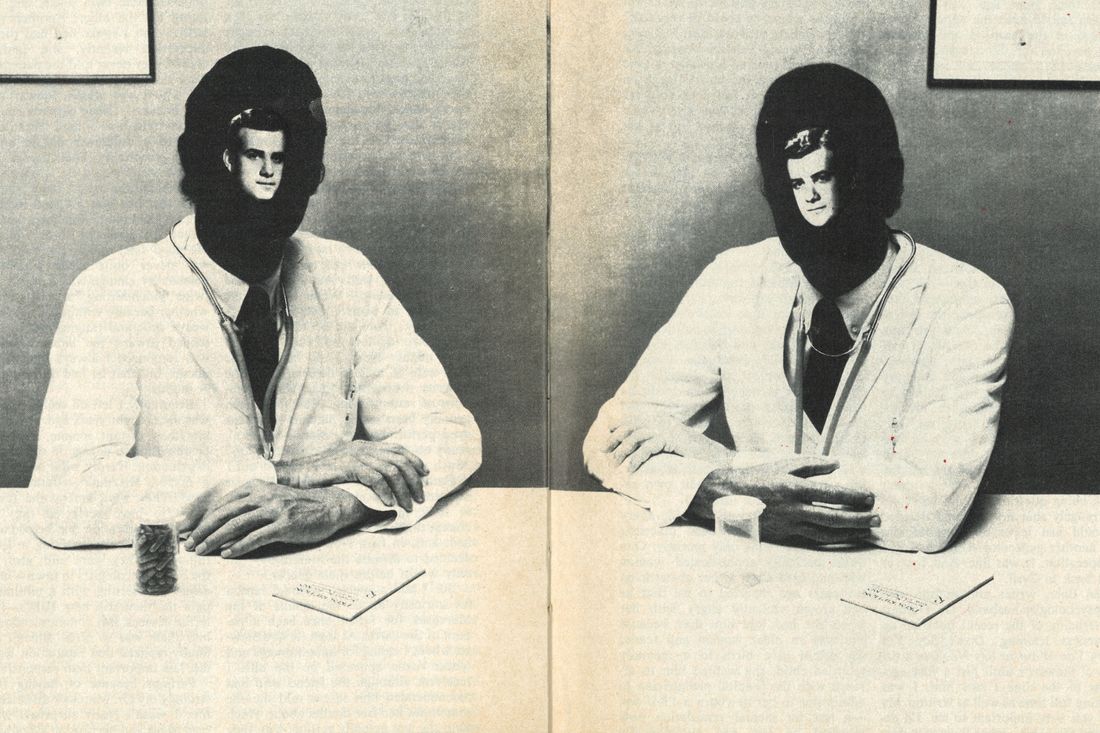

Several aspects of the deaths contributed to my stupefaction. One was the very fact of the men’s twinship, the doubleness which had given them a mutual birth date and now a mutual death date as well. Another was the men’s prominence. When beggars die in a state of bizarre deterioration in New York, there are no comets seen; when two doctors still on the staff of a mighty New York hospital die in a state of bizarre deterioration, the heavens themselves blaze forth questions of responsibility. Had these men actually been seeing patients — perhaps even performing operations — while already on their route to disintegration? (Such was the case, as it turned out.)

Had none of their learned colleagues noticed, if not a mental alteration then at least the clear signs of physical change that had come over them? (They had, and, in fact, New York Hospital decided to dismiss the Marcuses — but only weeks before their deaths.).

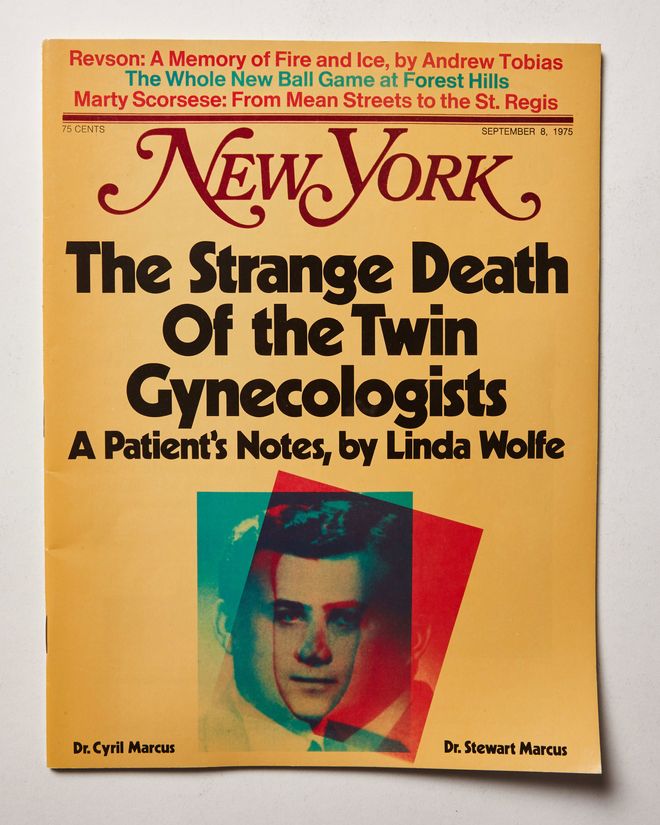

On the Cover

But I had a special personal reason for curiosity about the deaths of the Marcuses, for I had once been a patient of Stewart’s. At least, it was Stewart whom I called for appointments and whose name appeared on the bills I received, although the friend who had recommended him to me told me she sometimes had her doubts about which twin she was actually getting. Yes, they were that much alike. She was convinced that from time to time they had played classic twin jokes, one substituting for the other. Another woman with whom I spoke had had the same impression recently, and said, “Of course, they never told the patients they were doing this. But I got so I could tell which was which. Stewart’s neck was thicker.” Other patients could tell which twin was which because they detected a difference not in anatomy but in personality. Their doctor, kindly on one visit, would be strangely inaccessible on the next. Thus, the story grew that one was a “good twin,” the other a “bad twin.” But there was widespread disagreement as to which was the good one, which the bad. And it was never quite clear whether the personality change was a result of the twins’ pinch-hitting for each other, or whether because within each twin there was a split and ranging personality. I tended toward the latter belief, and was convinced I always saw the same doctor, but that he had dark and darker moods.

Eventually I left off seeing him. This was about eight years ago. I had found him/them distant, remote, incapable of or unwilling to engage in discussion or explanation. Hardly what one wants in a doctor. His/their reputations were good. They were among the few surgeons to have perfected the “purse string,” an operation that helped women who had difficulty carrying a fetus to full term. They were said, also, to be the best gynecologists in town — in those days — at inserting with a minimum of pain the then still new IUD’s — intrauterine devices. But communication with him/them was so often difficult that I finally realized that reputation was, for me, less important than responsiveness.

Perhaps because of having felt so strongly my Dr. Marcus’s distance from life, I wasn’t really surprised when I read of his and his brother’s deaths. The initial police reaction was that they were victims of a suicide pact. There were no signs of anyone’s having forced entry into their apartment; no signs of external violence to either body. Stewart was found face up on the floor, nude except for his socks; Cyril was found dressed in his shorts and face down on a big double bed. Stewart had died several days before Cyril. There was no note — the usual accompaniment to suicide — although according to Bill Terrell, the building repairman who called the police and, with them, was the first to enter the apartment, there was a piece of paper in a typewriter with the name and address of the woman whom Cyril had married and divorced.

More mysterious than the question of whether their deaths had been intentional or accidental was the fact that the cause of death remained unknown for days. Despite the fact that Cyril, a man close to six feet tall, had weighed just over 100 pounds at the time of his death, and Stewart had been gaunt as well, no sign of serious physical illness was found in either man. No cancer: no heart condition.

Ultimately, extensive tests conducted by the Medical Examiner revealed that drugs — barbiturates — had caused their deaths, but not because they had suddenly taken a large quantity. Rather, they had been taking large quantities for a long period of time, and it was when they stopped — and had the fatal convulsions typical of barbiturate withdrawal — that they had died.

It is not easy to portray the Marcuses. The relatives are loath to talk about them, for obvious reasons. The wife from whom Cyril was divorced has children whom he sired. She feels an enormous, brooding compassion for her ex-husband. Colleagues of the Marcuses and those in an administrative capacity at New York Hospital were even less willing to talk, although three weeks after all my attempts at interviewing them had been defensively rejected, the Times was able to shame them into finally addressing the press. Because of these difficulties, I had to follow another direction and it took me closer to a resolution of the personal questions troubling me.

I went first to the building in which the Marcuses had been found dead. Cyril had lived there — in apartment 10H at 1161 York Avenue — for some five years, apparently since the time he had separated from his wife and children; Stewart had moved in with him sometime in the last few months. To the doormen and building employees, the two doctors were always distant, remote, too arrogant for a “Good morning” or even a “Hot weather, isn’t it?”

Because the two doctors eschewed small talk. no one talked to them much after a while. Thus it was that on a Tuesday, the Tuesday on which, presumably, the second twin was to die, his brother having done so several days earlier, doorman George Sich — who had worked in the building for 25 years — saw one of the twins leave the building sick and depleted and yet was unsure about how far to carry an offer of help. The twin — we now know it was Cyril — neared a table in the lobby on which packages were occasionally placed and began to stagger a bit. “I thought he looked ill,” says the doorman: “I thought he was going to faint, and I hurried over to help him.” But when Sich reached his side, the twin recovered his balance and said in an icy tone. “I’m all right.”

Inside the apartment that day, the other brother — Stewart — already lay dead. He had become just another part of the debris and decaying organic matter that had been collecting around the twins for a lengthy period of time. The newspapers described the apartment in which the bodies were found as “messy.” Stronger words were used by building employees and policemen who went into the rooms. In the room in which Cyril died there was no inch of floor space that was not covered with litter and garbage, not just in a single layer, but almost a foot and a half high. Bits of unfinished TV dinners and chicken bones, paper bags and sandwich wrappers from Gristede’s were heaped around the bed, a collection of plastic wraps from the dry cleaner’s entirely filled one closet, and human feces rotted in a handsome leather armchair of the type so many doctors favor.

Bill Terrell, the building repairman, says that he knew from the first that there was a dead body within. Neighbors had been complaining for two days that there was a smell emanating from 10H. Terrell says, “I knew what the smell meant. I was in combat, you see. The real conflict.”

But Terrell had reasons beyond the nose on his face to suspect that there was a dead man — or two dead men — in the apartment. Once before he had been called upon to break open the door to 10H. It is his story of this event that makes the death of the Marcuses seem not just a sudden inexplicable tragedy but a tragedy with long, concealed roots. That other time, about three years ago, Terrell had been passing by 10H on his way from a repair job in a nearby apartment when he heard a buzzing sound within. It sounded like a phone off the hook. He thought nothing of it until, several hours later, he had cause to be on the tenth floor once again, passed 10H, and once again heard the buzzing. This time he rang the doorbell and began to pound loudly on the door. When no one answered his noises, Terrell says, he got the phone number of Cyril’s brother Stewart and telephoned him at his office. Terrell said to Stewart, “There’s something not quite kosher at your brother’s place. I think your brother needs help.”

What happened next amazed and intrigued Terrell. There was, he says, a long silence. He got the feeling that Stewart was somehow consulting the air waves, communing with his brother, because he said nothing for a long, long time and then, quite abruptly, said, “Yes, You’re right. He does need help. I’ll be right over.” In Stewart’s presence, Terrell took apart the door lock. When they entered the apartment, they saw Cyril lying unconscious in the foyer. Stewart turned pale. Terrell said, “Give him artificial respiration.” “I can’t touch my brother. You do it.” “I can’t,” said Terrell. “You’re the doctor. You do it.”

But in the end, neither of them did it. Stewart was too shaken and Terrell went to call help and an ambulance. It arrived within minutes, and one of the doctors who came rushing in saw Cyril and said, “Boy! He’s just about had it.”

There is still, I think, some primitive terror of twins that lurks in us. It is so strong that, although we have come eons away from the kinds of superstitions that drove the Aborigines of Australia to murder one or even both of a twin set at birth, or some West African tribes to kill not just twin infants but the woman who had given birth to them, we are nevertheless mysteriously stirred and frightened when twins, born on the same day, die — or worse yet choose to die — at the same shared time. It arouses in us an almost primordial anxiety. How can it happen? It can’t, and yet it does. It happened here in 1952 when two ancient twin sisters were found withered from malnutrition in a Greenwich Village apartment, only to expire within hours of each other and their discovery. It happened in a North Carolina mental institution in 1962 when twin brothers, hospitalized for schizophrenia, were found dead within minutes of each other in separate ends of the hospital. The simultaneous or nearly simultaneous death of twins happens rarely, but when it does, it seems like some mysterious arithmetical proposition far beyond the ordinary computation involved in life and death.

And yet sometimes there was humor connected with the Marcuses’ twinship. Once, when they were interns at Mount Sinai, they had participated in a hospital show, one twin exiting stage left just as his brother entered stage right, dressed alike, moving alike, trick photography in the flesh; it brought the house down. But for the most part, the stories that have accrued around the Marcus brothers are neither humorous nor focused on their attractive looks, nor even on the outstanding gynecological textbook they wrote in 1966.

The words used to describe the Marcuses by even the most psychologically unsophisticated — words like “remote,” “distant,” “icy” — are the classical language used in psychiatric textbooks to describe schizoid personalities. Although some years ago Cyril, when married, displayed photographs of his children in his office, and Stewart was known to talk admiringly of their doctor-father, in the last few years of their life they seem to have felt connected to no one, except, perhaps, to each other. They had always been extraordinarily close and had shared, in their adolescence in Bayonne, New Jersey, and their college days at Syracuse University, the same aspirations, achievements, and goals. Sometimes this caused distress in people around them.

One woman — a physician — recalls the Marcuses well because they were gynecological residents in the hospital where she delivered her first child 20 years ago. She remarked to me: “Having the Marcuses was a horrible experience; one would check with his fingers to see how far I was dilated — standard procedure, but never very pleasant — then he would call his brother, and have him check too. They did this twice. It was painful enough to have two people do it. And unnecessary. I finally had to have my husband demand that they stop this. It was as if one couldn’t have an experience without sharing it with his brother.”

At the same time, the brothers seem to have feared alienating each other. Or at least Stewart feared alienating Cyril. A woman who was Cyril’s patient and grew to dislike his personality nevertheless felt that the Marcus twins had an expertise with women who had previously miscarried and now wanted to give birth. On one occasion she recommended such a friend to Stewart, explaining to her friend that she was sure she would not be able to bear Cyril’s icy mannerisms. The friend called Stewart and said she had been recommended to him by a patient of Cyril’s. Stewart refused to see her. “I can’t take patients away from my brother,” he explained. The woman argued with him. “I am not Cyril’s patient; my friend was Cyril’s patient and she has recommended you.” Stewart, this woman recalled, “grew apoplectic and he said he would never see my friend or me.”

The Marcuses seem to have found in their twinship a proof of specialness, of their unique importance in a world of singletons. Sometimes that feeling was expressed in harsh, cruel ways. I know this because of a conversation I happen — eerily — to have had two weeks before the announcement of their deaths, with a woman who was explaining to me how it had felt to have twins. In retrospect, it seems amazing to me and to Arlene Gross that she and I had been talking about the Marcuses on a rainy Sunday as one of them already lay dying. Mrs. Gross had said to me that afternoon, “I didn’t know I was going to have twins. Still, I suspected it. There are twins in both my husband’s and my own families. But no one believed me. The obstetrician — a Dr. Marcus — certainly didn’t. On one of my visits I told him I thought maybe I was carrying twins, and he got peculiar, hateful and cold. I’ll never forget it. He stared at me and he said, ‘You pregnant women are all alike. Just because you overeat and get fat, you think you are going to have twins.’ He spoke to me with such contempt. It was as if I’d said I thought I was going to have the Messiah, as if giving birth to twins was something too special for the likes of me. Which was funny, since he was a twin.”

There is one essential of personality that emerges in all these accounts, whether they deal with the twins’ closeness, their feelings about their twinship, or their awe of each other. It is that they were frequently hostile, even hurtful, to their women patients. Curiously, in view of their ultimate gaunt condition, they often seemed to insult women about their weight. The woman who gave birth to twins had been told she was fat; still, she was heavy at the time and she felt that the insult had been just, if cruel. But another woman who was five feet, eight inches tall and weighed, toward the end of her pregnancy, 155 pounds — a gain of only 20 pounds over her normal weight — was told by Cyril, “You’re disgustingly obese.”

And there is another common thread in the accounts patients give of the Marcuses. It is that they could not abide disagreement. They seem to have grown paranoid and angry whenever they were questioned. One woman I spoke with tells an anguished story of being scheduled by Cyril for an operation three years ago, only to have had him fail to keep the appointment. She was in the hospital and already being prepped for the operation when she received a phone call from him. He explained to her in ordinary tones that the operation would have to be delayed till the afternoon because the doctor who was using the operating room at present was running late. The woman accepted the explanation. Afternoon came and once again the nurses started prepping her and once again there came a telephone call from Dr. Cyril Marcus. Again, still reasonable, he explained with some solicitude that he could not perform the operation. He would do it the next morning. When he called her the third time — the next morning — he suddenly announced that he had decided to postpone the operation and do a biopsy. “And this was the odd part,” said the woman. “I had always before found him pleasant, nice. When he told me — and later my husband — that now he had decided to do something different with me instead of operating, we felt it was certainly our right to know why he had changed his mind. But once we began questioning him he flew off the handle, became overwrought. He couldn’t brook being questioned. And he spoke so strangely that my husband decided I should just leave the hospital and seek another gynecologist. I did. I had the operation. It was fine. And I never went back to Cyril.”

Jean Baer, writer and author with her psychologist husband, Dr. Herbert Fensterheim, of the recent book on assertiveness training Don’t Say Yes When You Want to Say No, was a patient of Stewart’s until just a year ago. “Most of the time I saw him, I was working full time as well as writing. My time was very important to me. I’d developed the habit — when it came to doctors and dentists — of always calling their offices prior to setting out from my home for appointments, just to be certain they weren’t running late. Several times when I’d call before an appointment with Marcus, the secretary there would tell me, ‘Yes, he will be free in 15 minutes,’ and so I’d leave my office and get up there, but when I’d arrive, he’d be nowhere to be seen. And it wasn’t as if the secretary had made a mistake. I could see she was embarrassed. She had no idea where he was. She’d just been told to answer calls that way. I’d have to wait and eventually he’d show up. But worse, once I needed him in an emergency and the secretary told me he never left a number where he could be reached.”

Despite these provocations, Ms. Baer continued seeing Stewart Marcus. She even continued seeing him after a time when, just before she was to leave on a vacation, Stewart failed to keep his promise to see her, and Cyril — telephoned for advice — lashed out at her over the wires.

“All I wanted was to know whether Stewart was going to be able to see me before I left and, if not, what to do about a certain problem I had. Cyril started screaming. I mean screaming. No one has ever spoken to me that way in my life.”

In my own experience, I can think of almost no other occupation but medicine in which explosive, paranoid, peculiar behavior is so long tolerated. In an office, in a shop, even in political life, there are checks and balances and interactions which eventually serve to inform and protect and dissuade the public. This is not true in medicine with its private-practice secrecy and the unwillingness of doctors to criticize their peers. Patients can, of course, leave doctors. But there IS almost no way they can communicate to other, less-wary patients what their own experiences may have unveiled.

Nor had the kind of excitable, angry behavior which Ms. Baer describes arisen in the twins only recently. One quite medically sophisticated woman who had used Cyril as her obstetrician ten years ago reported to me that he had grown violently angry with her when she had told him that, because she was an older woman and feared she might give birth to a mentally retarded child, she wanted him to arrange with the hospital pediatrician to administer to her newborn a PKU test — a test for mental retardation now required by law and automatically given to all infants born in New York State. The test was not yet law at the time, however, and Cyril Marcus was enraged at the request. He told the woman the idea was ridiculous, that he had not even had the test for his own children, and that she was being grossly demanding. Shortly before she gave birth, the test did become standard procedure, but, if anything, this made Cyril even more angry and hostile to her.

What of their colleagues? While they speak less freely than do the patients, they too reveal a dark side of the doctors. Dr. Myron Buchman, a prominent New York Hospital gynecologist and longtime colleague of the Marcuses’, says, “No one really knew them well.” Another doctor at New York Hospital with whom I spoke said, “No one was shocked at their deaths. They were isolates and had always kept to themselves.” A third gynecologist, Dr. Stanley Birnbaum, said, “There was no one they were really friendly with at the hospital,” and explained, “everybody felt they were sick, somehow, but just what was the nature of their illness, if any, I have no idea.”

In general, the picture that emerges of the Marcuses is of two men who shared a psychological disturbance that antedated their extreme barbiturate addiction and eventual death. It is common for identical twins to share psychological traits and capabilities as well as physical similarities. Thus we have had many sets of twins who enter the same professional field as one another and achieve almost equal prominence — the playwrights Anthony and Peter Shaffer, the painters Raphael and Moses Soyer, the doctors Alan and Manfred Guttmacher. Identical twins tend to resemble each other — even when reared in different households and economic settings — in such things as IQ, mathematical ability, musical talent, degree of self-confidence, and even in mental disease and the rate at which it develops. They do not show a greater incidence of such disease than do other members of the population, but when one twin develops a mental illness, the risk of its development in the other is very high. Illustrations of this are so dramatic and convincing that twin research has become the backbone of the growing psychiatric conviction that such mental illnesses as schizophrenia and manic-depressive disease are genetically transmitted.

It is therefore not unlikely to assume that both the Marcuses deteriorated from the same mental illness at the same rate. Nor is it necessary — or even sensible — to ask, “What made them die?” if the implication of the question is, “Who did it? What woman or man? What disappointment?” For many years the brothers had been withdrawn, isolated, suspicious. At some point they intensified their isolation by seeking the increased withdrawal and somnambulism that barbiturates offer, and in the end they opted for — or simply grew too weak on drugs to consume any more and thus ward off — the ultimate somnambulism of the grave. Theirs is a story of a slow groping toward death on the part of two men who already had but a tenuous connection with people — and that connection, after all, is life.

Thus, in the operating room one day last year, one of the Marcuses pulled the anesthesia mask off a patient and placed it over his own face, longing for unconsciousness and extinction. It was for this — and other similar reasons — that so many of those who knew the Marcuses said they were not surprised by the brothers’ death, and seemed even to have anticipated it. But why hadn’t they shared their suspicions, blazoned them about town? And why had New York Hospital waited so long to initiate the twins’ dismissal, when years ago the brothers were already showing signs to patients of dangerous mood shifts and impersonality?

These days, I find I am disillusioned with all the colleagues of the Marcuses who knew how sick and unreliable the twins were, but who felt it necessary, out of medical solidarity and a self-serving sympathy for troubled peers, to keep silent — up to and even after the bitter end. I find I keep asking myself, Who was that woman whose anesthesia mask was removed? It might have been me or you.

Related

- Who Can Top Rachel Weisz?

- Jennifer Ehle Based Her Dead Ringers Investor on Ayn Rand

- Which Mantle Twin Did What in Dead Ringers