Occasionally, it is necessary to convene a conversation between Vulture writers to discuss an important and timely issue in culture. This time, Vulture TV critics Jen Chaney, Roxana Hadadi, and Kathryn VanArendonk have gathered to discuss the flashiest element of a series with no shortage of flash.

There’s a lot to say about Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty, the new HBO series from Adam McKay about the creation of the modern-day Los Angeles Lakers. There are performances by John C. Reilly, Gaby Hoffmann, Tracy Letts, and Jason Segel, plus a notable role for newcomer Quincy Isaiah as Magic Johnson. The show is full of music, women, drugs, drama, and, obviously, basketball. Yet the most immediately striking thing about Winning Time is how it looks. Its visual style is impossible to ignore. Is that a good thing? Let’s talk it out.

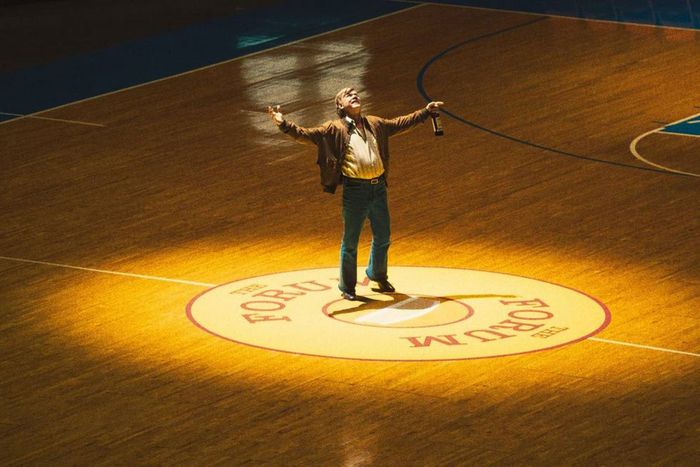

Jen: The sensibility of Winning Time is, to put it mildly, aggressive. As I noted in my review, there are many flourishes throughout the episodes that feel very Adam McKay-ish, even when he’s not directing. (McKay is an executive producer and directed the pilot.) There’s a ton of fourth-wall breaking and talking directly to the audience. Text sometimes appears onscreen to accentuate a point, like how much Dr. Jerry Buss (Reilly) is spending on his purchase of the team. There are also moments with animation, retro footage, shots that appear to be filmed as home movies, and an overall visual look that evokes the fuzzy appearance of something shot in the late ’70s or ’80s. In short, it’s a lot, and the viewer needs to hop onboard with the approach or risk being left behind.

The question at hand is: Why did the makers of Winning Time go this route? And is it effective, or is it distracting? Kathryn, I’ll throw to you first since I have the impression you were not a fan.

Kathryn: I’ll admit it — the first thing written at the top of my Winning Time screener notes is the big all-caps question “WHY DOES WINNING TIME THINK IT NEEDS TO LOOK LIKE THIS?”

You’ve laid out the list of what “like this” might even mean already, Jen, but for me, it really falls into two separate categories. First, there’s the way the show breaks the fourth wall, that familiar Adam McKay tic that has characters using direct address to explain exactly what’s happening. That is its own whole ball of wax. But on top of that, there is the larger visual style, which could be called “distinctive” or “vintage” or “fuzzy” or could also be described as grungy, dingy, blurry, smug, scattershot, distracting, unnecessary.

It’s funny, the visual aesthetic is clearly meant to evoke masculine signifiers. It is a wildly male-gaze-y show full of boobs and cool dudes looking at a camera being cool. There are even shots that linger on gratuitous violence, which I was not expecting in a basketball show! This is my fault for not knowing the story. But the other way to think about the overall visual and narrative impact is that it is overwhelmingly ornamental. Any time a shot could have one idea in it, there are seven. Any spare second where an establishing image might evoke a particular feeling, Winning Time wants to pile on at least four additional thoughts, often by literally piling them on, overlaying one image with several others, as though our narrator is stacking out-of-focus snapshots on top of one another in a rapid-fire heap of evidence. Yeah, I find it distracting, and I think even for a viewer who loves it, which is a completely legit response, it seems indisputable that a style like this is meant to be distracting! Whether it’s effective, though — that feels like a trickier question.

Roxana: You know, I do think it’s effective! Perhaps I am a little more susceptible to McKay’s “throw everything, literally everything, at the screen” approach, which I liked very much in films like The Other Guys and The Big Short. But those were two-hour movies, and that shorter run time might have been easier to become accustomed to than eight one-hour episodes of Winning Time.

What I will say in defense of this stylistic deluge is that it kept my attention and forced me to switch perspectives in a way I found immersive. A typically shot scene in which two people are arguing about the future of the Lakers gets some added context when a grungy filter is layered overtop, a reminder that we’re peeking into the past. A fourth-wall-breaking cutaway provides depth for characters who aren’t always in the limelight; I’m thinking of a scene in a later episode where a white comedian is making a racist joke and we cut to a Black player mouthing “What the fuck?” Those moments serve as underlines and exclamation points, and I think a show that is analyzing excess and glitz — and how slippery and repellent so much muchness can be — benefits from being a little self-aware in incorporating those very things. Will I defend Don’t Look Up? Never! But I must admit that I felt challenged by Winning Time in a way I appreciated. Am I losing it? Do I need a reality check?

Jen: I realize this will sound wishy-washy, but I see both sides of this. I agree with Kathryn that the approach can be overwhelming, especially in the first episode. Kathryn, you used the word smug, and I think that’s part of it: Initially, the series gives off this hypermasculine “let me explain the world to you” energy that rubbed me the wrong way, especially because I had just come from watching Super Pumped, which has some similar qualities. There’s a moment in the second episode, which was directed by Jonah Hill, when Magic Johnson (Isaiah) beats the guy who’s dating his former girlfriend in a game of pickup ball, which quickly flashes to a dog humping another dog. That kind of stuff feels very bro-ey and, for me, off-putting.

However, to Roxana’s point, the aesthetic of the series is so in your face that you never forget you’re watching a show. That feels appropriate for a drama about a team aiming to make NBA basketball flashier and more over-the-top, to turn the games into Hollywood-level entertainment. As for the muddy, late-’70s look of the whole thing, I warmed to it because it really does evoke the era very well, and when I try to imagine watching this story via the crystal-clear pixels of HD, I realize that would have taken me out of the story too, in a different way.

Let me ask this: Did you find yourself getting used to the whole go-for-broke Winning Time ethos the more you watched? Because I did, and especially in the upcoming episodes directed by Tanya Hamilton and Damian Marcano, I was more engrossed in the story and less distracted by the flair, for lack of a better word.

Kathryn: As I get deeper into screeners, I am less overwhelmed by the look of it. But my experience is less about warming to the show’s visuals and more about eventually getting hooked enough into particular characters and the very hooky sports-story tropes that I just don’t care as much. It feels a little like Stockholm syndrome.

I keep wondering if I’d have been more comfortable with the overall experience if it had just been one thing or the other. Either have characters use direct address, or use a billion cameras and filters and intercut imagery. They’re both devices that refuse to let a viewer rest. Maybe with one or the other, the exhaustion would be less extreme.

At the same time, I have made it deep enough into this season to understand that the show’s aesthetic is also exactly the thing Dr. Buss is trying to create for the branding of this team, as well as being a beautiful visual adaptation of the free-flowing, perpetually moving style of basketball that distinguishes the Lakers from everyone else in this era. Intellectually, I can appreciate that! As a viewer, I find I’m still mostly trying to ignore the show in the service of watching the show.

Allow me one small, non-spoiler-y example from episode four, a scene where Dr. Buss is talking with Claire Rothman (Hoffmann) by the pool. She’s raising all kinds of very practical and boring questions about financial feasibility; he is listening and mostly ignoring her while consuming a gargantuan platter of seafood. She speaks, he responds, but in one of his responses, there is a cut. First, we go from his face as he’s replying to her, then for a few seconds, the audio track continues with his reply while the image cuts to him sucking on a crab leg. It’s disorienting. It feels like a little hiccup, and your brain registers the change. And yeah, it serves a purpose. When the image bifurcates from the dialogue, we get two levels of information rather than one. But that added level doesn’t change anything! He loves luxury and excess. It’s something we knew from previous episodes, something that was already established by the scene, and now something that’s been underlined again in yet another way. My brain was more full. That little choice snagged at my attention. But what did it add?

Roxana: You raise a worthwhile question, Kathryn. What if Winning Time used just this purposely aged look or used just direct-to-camera explanations and asides? Is one approach more successful than the other? I think the show unintentionally wades into this in episodes that aren’t directed by McKay. His pilot certainly sets the tone and style for Winning Time, but by, say, the fifth episode, “Pieces of a Man” — the exemplary Kareem Abdul-Jabbar–focused installment directed by Hamilton — the direct-address flourish has taken a bit of a back seat. I think there might be only one or two uses of it in the entire episode, and frankly, I didn’t miss it.

Visually, I’m really drawn in by the oppositional compositions, by switching back and forth between cameras and filters, and by the cumulative impact of feeling both like a fly on the wall and like someone scrolling back through old VHS tapes to watch decades-prior games. Netflix’s Archive 81 uses this approach too, to differentiate between the present day and the 1990s, and I liked it there as well. In Winning Time, if we were only being drawn in through affect rather than address, perhaps the snarky tone wouldn’t rankle so much. It does get a little trying to be caught in the cycle of “This is exactly what this situation was like because I, the creator of this show, am explaining this to you, the entrapped viewer of this show.”

McKay establishes this approach for teaching moments throughout the series, and at a certain point, my reaction became, Dude, I get it, I don’t need an explainer on the first person who ran a sub-four-minute mile to understand how basketball works. That contextual rigidity becomes unnecessary once the series has established what it’s going to do, and the pilot does that fairly well already. If Winning Time were only showing rather than also telling, would it go down easier?

Jen: Roxana, I agree about the runner story, which felt like it could have been shorter or cut altogether. But given the scope of what Winning Time is trying to do, I think there are cases where the explainers are very helpful. One notable example is when Coach Jack McKinney (Letts) explains, mostly via narration, how traditional slower basketball was played, versus the quicker, freer version he devises that became the default way the game is played since then. The show could have just incorporated that information into dialogue, but that might have weirdly seemed more forced than doing it this way.

Yes, the series tells at times when maybe it could show, but the telling also feels like part of the show — and, now that I think of it, emblematic of how sports culture and conversation function. Have you ever watched a show on ESPN or listened to a sports podcast or talk-radio show where everyone doesn’t act like they are absolutely right and an expert on the game? Winning Time channels that attitude, and while it can be irksome, it also feels spot-on for what this show is trying to do. Again, I come back to the idea that this is the story of the Lakers under Jerry Buss and Magic Johnson, both dudes who, during this time, had serious issues with restraint.

It’s true that Winning Time doesn’t give the viewer a chance to rest, but again, that’s the point. A constant-motion offense, the strategy implemented by McKinney, goes hand in hand with a constant-motion TV show. I think the sense of urgency comes through more forcefully because of that. As Kathryn mentioned, Winning Time is unable to dig into some of the broader issues it raises about things like racism within the league and, to a lesser extent, the misogyny that is rampant within this culture. When you’re moving this fast, there’s little time to dive deep, which is a flaw for sure. But I think the makers of Winning Time prioritized making this a visceral experience above all else, and it certainly is that.

More From This Series

- Was Winning Time a Loss Or a Victory?

- Winning Time Finale Recap: Leave the Dynasties to Us

- Winning Time Will Not Shoot for 3